review | Broadway Danny Rose

also on Cineluxe

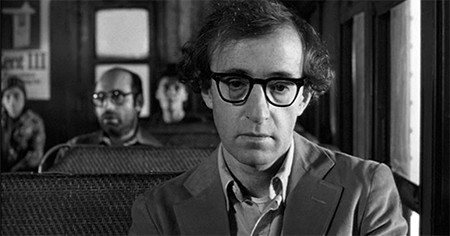

An unnecessarily rough diamond, but still Woody Allen’s most charming, and deeply felt, miniature

by Michael Gaughn

posted July 8, 2021

Indulge me for a moment while I begin with a digression. I had been surveying Woody Allen’s films on Kaleidescape because its recent acquisition of the MGM/UA catalog had seriously upped the number of Allen titles on the service. But what had been a steady stream has recently trailed off to a trickle, and two of his most crucial efforts—Broadway Danny Rose and Zelig—have stubbornly refused to appear. Wanting to wrap up my perusal, which was always meant to be a prelude to writing an appreciation of Allen, I turned, really, really reluctantly, to Amazon to bail me out.

To be blunt, HD movies streamed on Amazon tend to suck—bad. And when I watched Danny Rose on there a few months back when I’d first been toying with a review, the quality was so awful I couldn’t bring myself to write it up. But something has changed. I don’t know what it is, and I’m curious to hear if anyone has an explanation, but the HD movies I’ve watched on Amazon recently have looked pretty damn good. To deliberately mix things up, I watched a black & white film from the ‘40s (Murder, My Sweet) and a color film from the early ‘90s (The Fisher King) just to make sure this wasn’t a fluke. And while I haven’t yet dived deep enough to know anything definitively, it looks like Amazon might have finally gotten its HD act together.

Which means I can finally review Broadway Danny Rose without having to liberally sprinkle the text with caveats and apologies. Rose is undeniably one of Allen’s best films—which doesn’t mean it doesn’t have problems. It does. A lot of them. But the fundamental impulse behind it is so strong and so brilliantly realized that the many fumbles actually, somehow, add to the experience.

For instance, the yarn at the center of the film is supposed to be set in the early ‘70s, but Allen shot it in mid-‘80s New York without changing a thing. Everybody drives those godawful 1980s cars, wears those godawful 1980s cloths, etc. There’s even one shot that prominently features a marquee for the very un-‘70s Halloween III.

And it’s implausible that Allen’s character would pick somebody up in the early afternoon for an eight o’clock performance at the Waldorf Astoria, but Allen deploys just enough smoke and mirrors to keep you from focusing on something that could have easily sunk a lesser film. Equally implausible is Sandy Baron’s telling of the story that provides the movie’s frame, which veers from feeling like a raconteur’s show-biz tall tale to sounding like he’s reading from a Mailer novel.

And yet Danny Rose somehow transcends all that—probably because its love for the sausage-making of show business is so obvious and runs so deep that it’s infectious, and you don’t really care how the story is told as long as it stays true to the roots—which it does.

This is probably Mia Farrow’s best performance in an Allen film—probably because she’s not allowed to get lazy and just play Mia Farrow again but actually has to develop a character; and not just a character but an against-type comic character that could have easily tumbled into jokey caricature if she hadn’t displayed enough discipline.

Allen isn’t quite as successful playing Rose—which became the basis for the annoying pipsqueaks he later leaned on in films like Small-Time Crooks, The Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Hollywood Ending, and Scoop. But he maintains a firm-enough hold on Rose’s basic enthusiasm and decency, and blind devotion to the business, that you’re willing to roll with the shortcomings. Similarly, Nick Apollo Forte is just able to hold together the Lou Canova/Tony Bennett character, but it works partly because Canova is supposed to be something of a delusional dope—a level of acting Forte easily achieves.

Broadway Danny Rose is a yarn, a tall tale, a fable. Given that, it could have easily gone too broad. But Allen keeps it focused on the characters and not the action, and the film works best when he lets these slightly larger-than-life people just be people, when he gets beyond the backstage gossip to something that feels like what it must be like to be trying to get by in a business whose only meaningful yardstick is ridiculous levels of success.

Gordon Willis’s black & white cinematography goes a long way toward selling the film. Color, no matter how restrained, would have felt too big, too current. The black & white images help to place it someplace other—a kind of netherworld of subsistence-level show-biz that, at the end of the day, is still better than having to hawk storm doors and aluminum siding and offers a hell of a lot more chances to brush up against greatness—illusory or otherwise.

In a lot of ways, Rose resembles Barry Sonnenfeld’s Get Shorty—another puckish fairy tale about the necessary muck of show biz that exists below—sometimes just below—all the glamor and pumped-up success. Both films capture the inevitable desperation, but both also make it clear why the denizens gladly inhabit these worlds instead of settling into a nice, quiet place in the suburbs.

Coming off the success—commercial and creative—of Annie Hall and Manhattan, Allen could have spent the ‘80s churning out archetypal Woody Allen films but instead used that decade to try on new clothes, seeing what, if anything, would fit. And it yielded some stunning achievements and some noble failures, with few efforts that weren’t worth the audience’s time. But as his inspiration started to fail, it left him with little to lean on as he approached the turn of the century. Rose was about the last time he was able to take a modest premise, keep the proportions right, and yet have the material yield something completely satisfying.

His most charming, and deeply felt, miniature, Rose is a kind of valentine to the part of the business no one gets to see, and a reminder that it is a business. No one but a long-time insider, and a eager collector of the lore, could have told the tale this neatly or compellingly. The best Allen films are the ones where you feel like you’ve been granted temporary access to a world just off to one side of the tedious, grinding norm, which is why Rose ranks right up with masterworks like Hall, Manhattan, and Stardust Memories.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC

PICTURE | Gordon Willis’s cinematography is only minimally well-served in HD on Amazon. This film ought to have a 4K release, but with practically none of the Allen catalog having made that migration, nobody’s holding their breath.

SOUND | Do I have to say it again? This is a Woody Allen movie. As long as you can hear the dialogue, everything’s fine.