Great Video Wall Sound–Another Solution

Great Video Wall Sound—Another Solution

Famed acoustical designer Anthony Grimani offers his unique approach to solving the problem of where to put the center speaker in a video-wall home theater

by Dennis Burger

February 23, 2023

The problem of how to design sound systems to support massive LED video walls is one that continues to motivate audio professionals working in the luxury home entertainment space. We’ve previously discussed the root of the problem as well as one potential solution, but the fact is this is such a custom domain that it’s hard to imagine a one-size-fits-all panacea that provides optimal sound for every wall in every installation.

I recently spoke with Anthony Grimani, president of Performance Media Industries, Ltd. and co-founder of Grimani Systems, to get his take on how to best design a sound system to accompany a video wall. Before we dug into his patent-pending solution, though, I asked him to reiterate for me why this is a problem to begin with.

“When we’re looking at images on the screen, we want the voices of the characters to come out of the middle of the screen,” he says. “And the way we do that traditionally is we put three speakers behind an acoustically transparent projection screen. But what happens when you replace that acoustically transparent screen with a big, thick screen that won’t let sound through?”

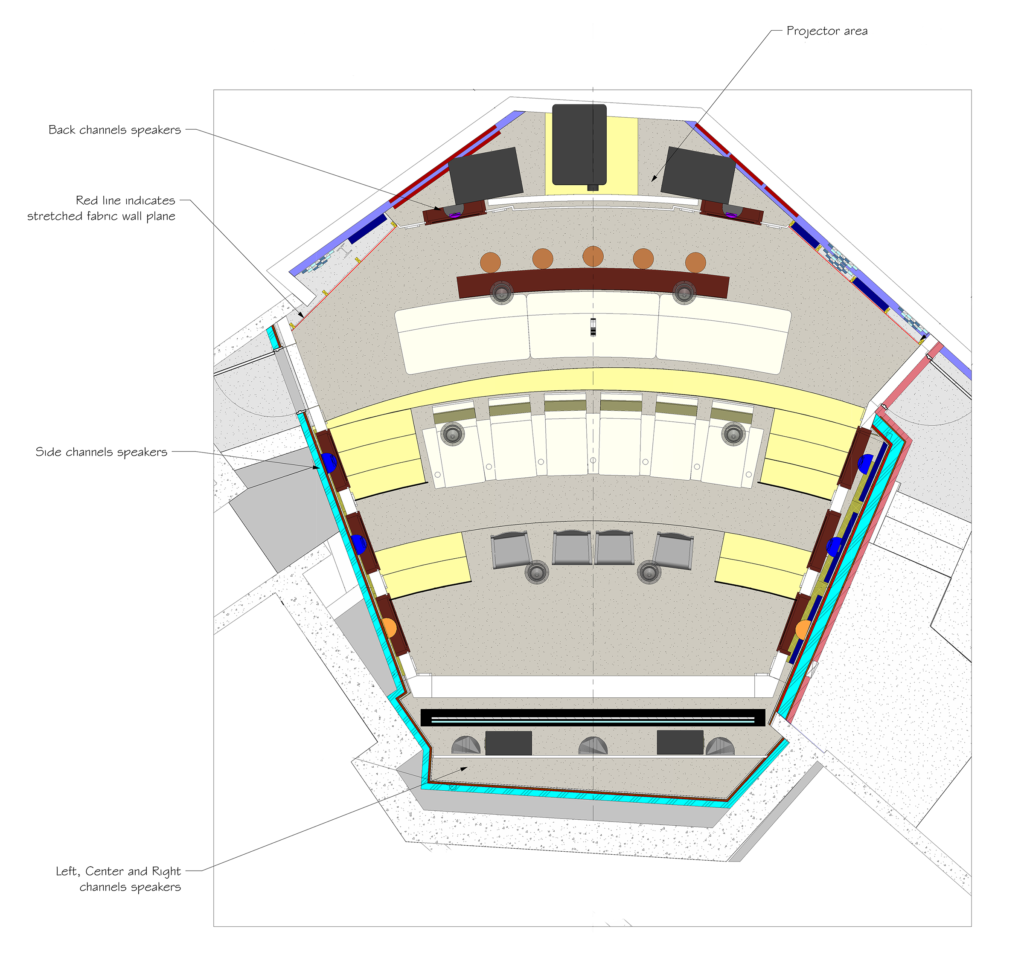

One alternative Grimani has employed is what he refers to as “Phantom+”—essentially using speakers on either side of the screen to create a phantom center speaker where no speaker actually exists. “The typical problem with a phantom center, though,” he says, “is that if your seat is off to one side of the room, the voices move with you. The character in the center of the screen now sounds like they’re coming from the left side of the screen.”

“But we’ve found that by using speakers with really good sound power—like ours, but also ones like Paradigm, KEF, JBL, and a few others companies that go through the effort of distributing the sound nice and wide and constant—that phantom center doesn’t move as hard and as much as with very directional speakers.” Add a bit of EQ to account for the way the listener’s head changes the sound arriving at their ears and this isn’t a bad solution, says Grimani. But it’s not ideal.

Another option—one that doesn’t share the same downsides as the Phantom+ configuration but has its own quirks—is a single speaker above or below the screen. “You might think it would sound like it’s imaging above the characters’ heads, because that’s where the speaker is. And if the speaker has a very focused directivity like a lot of people think you have to have, you’re dominated by the direct sound and you’re going to hear it as up above the image. But because of the wide directivity of our speakers—because what you’re hearing is some direct sound and then a lot of really broad sound-power energy reflecting off the lateral surfaces, there’s enough energy flowing around that it fools your sensation of imaging and you hear the sound centered not above the screen but toward the top third of the screen. You still hear the sound coming from the screen, just higher than perhaps it should.”

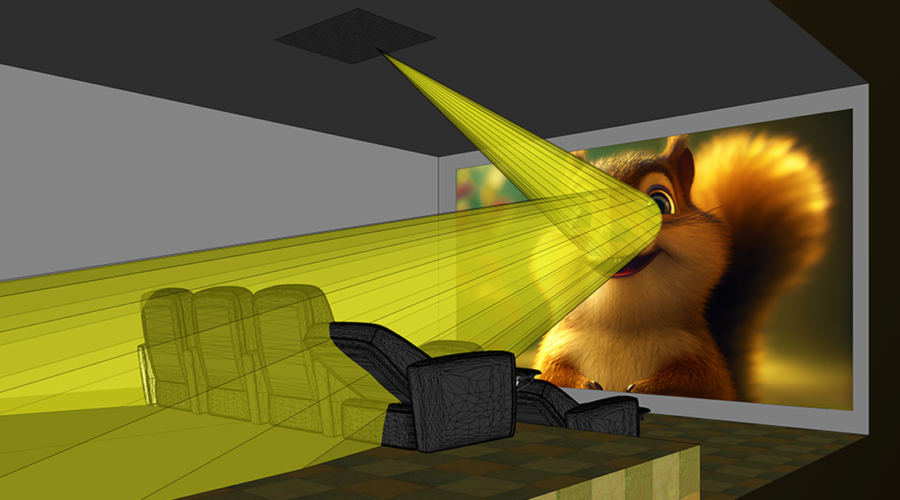

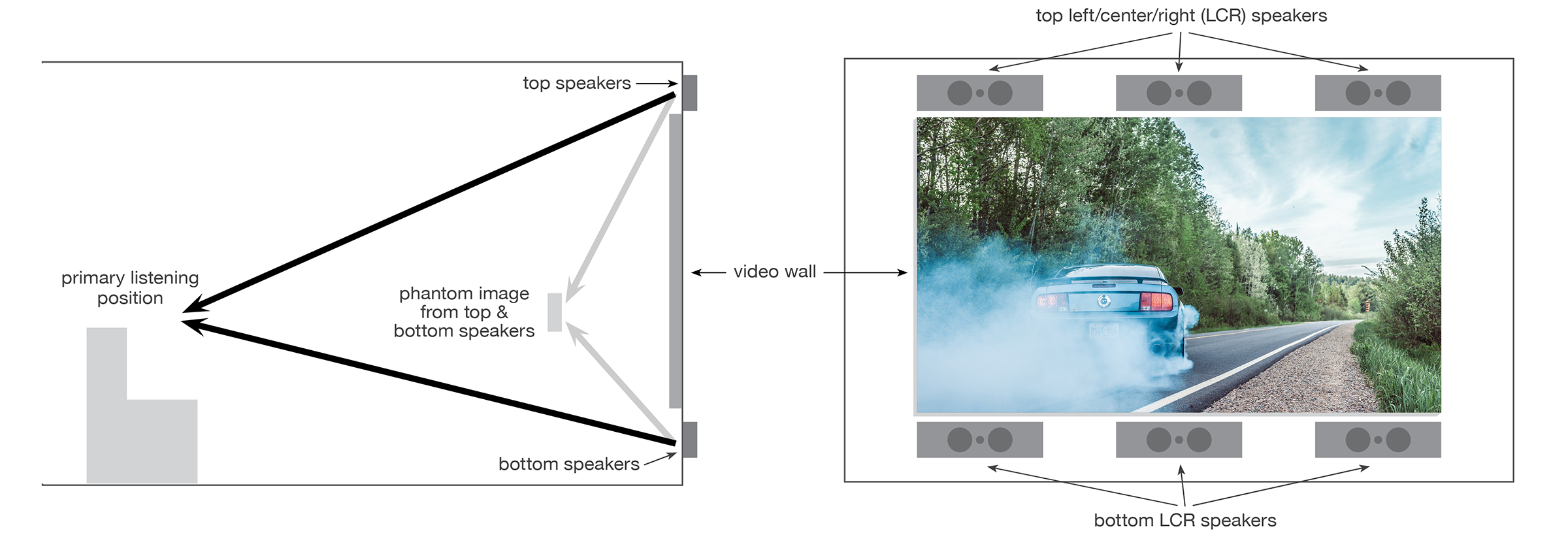

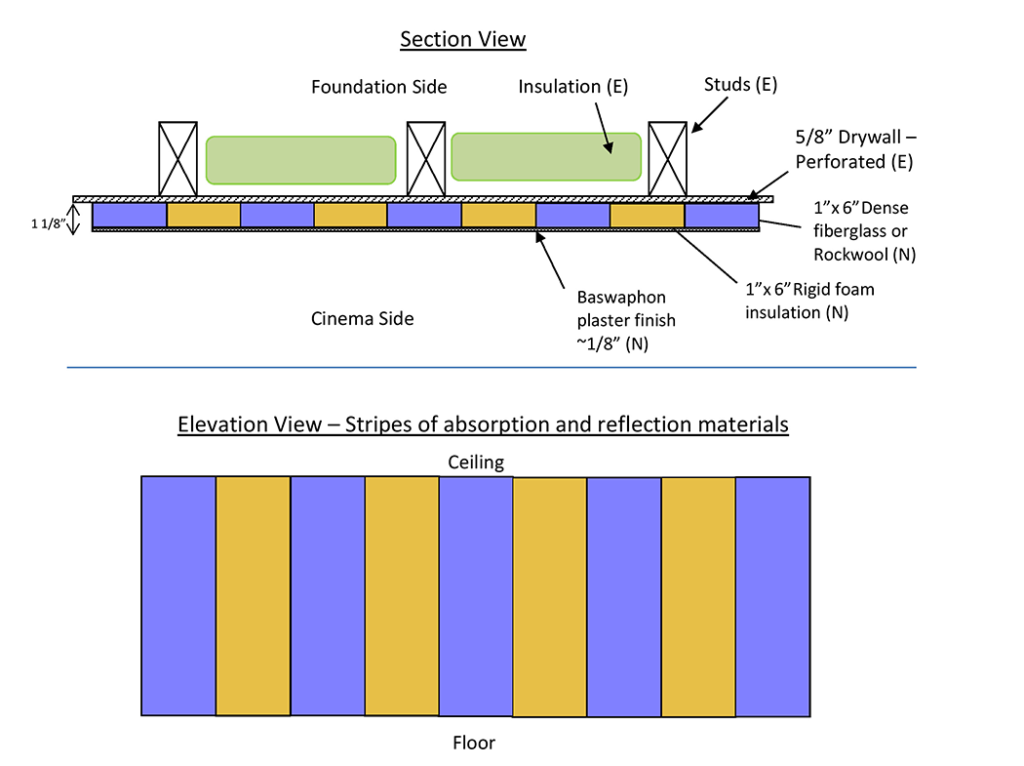

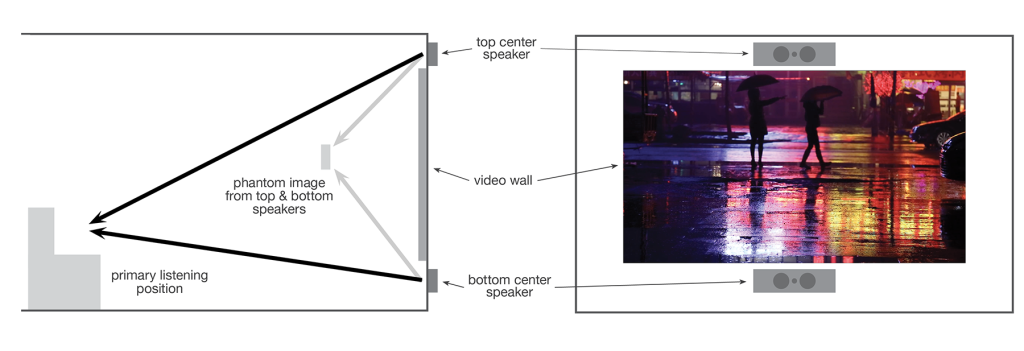

Then again, that really only works if there’s room above the screen for a speaker. And given that modular LED video walls are often installed floor-to-ceiling, sometime there simply isn’t room. And that’s where Grimani’s new solution comes in. In short, it works by splitting the sound going to the center channel into two parts: The lower-frequency sounds are sent to the speakers on either side of the screen, whereas the higher frequencies—the ones you can really point to and say “That sound is coming from right there”—are sent to a speaker above the listeners’ heads and aimed at the video wall, so they bounce off and seem to come from close to the middle of the screen.

That’s the simple explanation. For a more in-depth look that explains why and how this all works, we’re going to need to get a bit more technical. What follows is a transcript of my conversation with Grimani about the subject, edit for clarity and brevity.

So, with this two-piece solution, how do you keep the listener from feeling like the sound is coming from two different directions?

The idea is to use a directional waveguide placed generally over your head, and if there’s no spillover of direct sound from the waveguide to your head, you can create the illusion of sound coming directly from the center of the screen. If there’s any amount of direct sound that goes to your head from that overhead speaker, though, you will localize that because it’s the first sound to arrive at your head. It’s only three or four feet away from you. So it’s really important that there not be any leakage.

Now, the waveguide needs to be a pretty good size. Laws of physics are what they are. You can’t cheat that. If we want the crossover point at around 800 Hz, the waveguide is about 12 inches tall. But you can bury that into the rafters in between joists.

With the phantom-center information below 800Hz, you do have to time-align everything really carefully because the path from the speaker to the screen and back to your head is longer than the path coming directly to your head from the left and right speakers. So you have to delay the other speakers so everything arrives at your head at the right time, and that’s all done really easily in the digital domain.

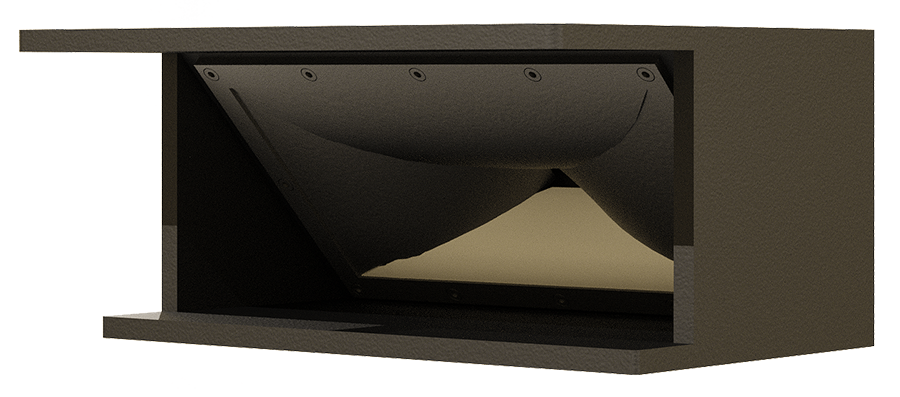

In terms of the overhead speaker, we happen to be using our Conic Section Array waveguide because it works well, but any other waveguide that produces good vertical pattern control with no off-axis lobes and wide-enough coverage works.

Full disclosure: If you sit right in the middle of the room, the image is slightly above the middle of the screen because that speaker bouncing off the screen is creating a mirror image, so it’s sort of like the speaker exists in a mirror-image position behind the screen. If it’s 12 feet from the speaker to the screen, it’s sort of like the sound is coming from 12 feet behind the screen, but in the ceiling. And if you move off-axis, that speaker does move with you a little bit. Imagine having a speaker shooting through an acoustically transparent

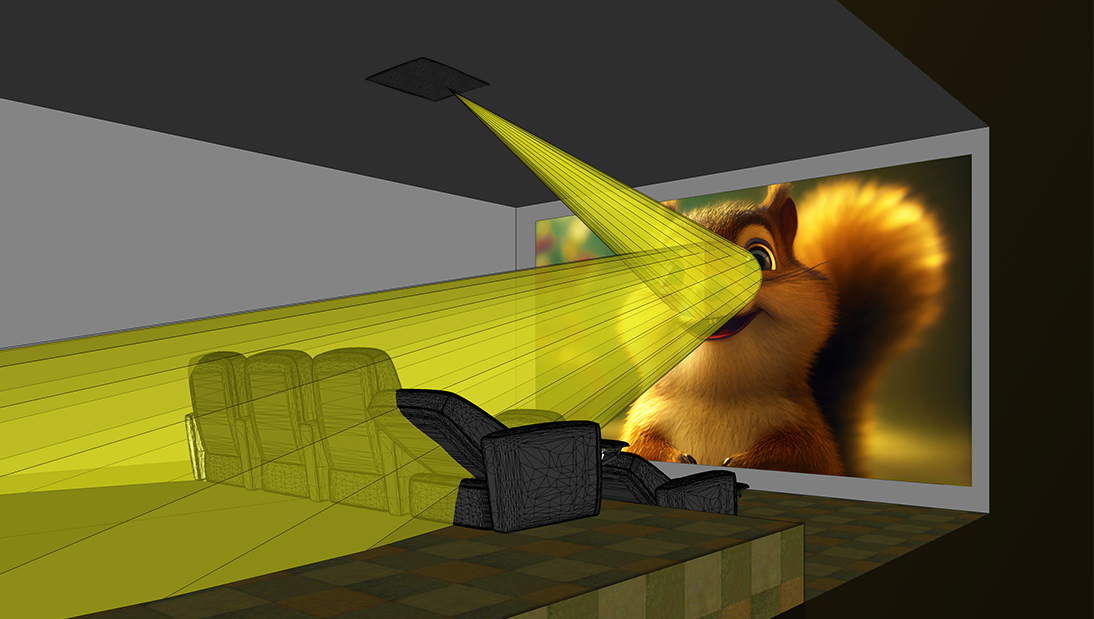

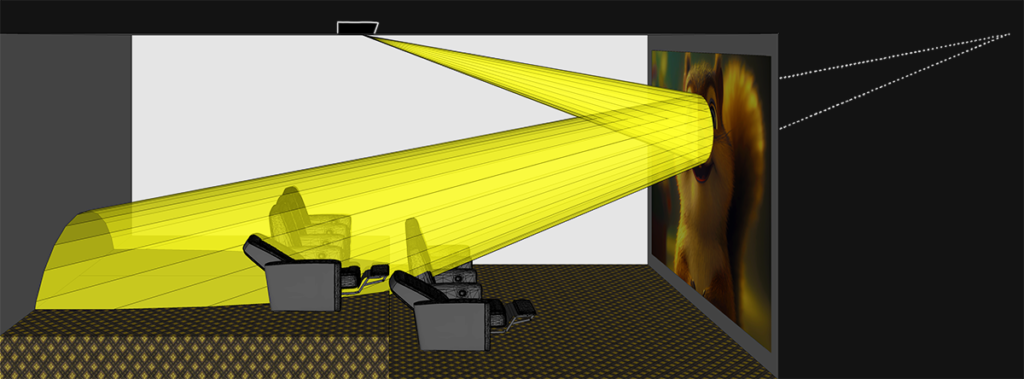

Since speakers can’t be placed behind a video wall as they can with a projection screen, the higher-frequency sounds are instead bounced off the screen and back to the listeners.

Anthony Grimani

Anthony Grimani’s solution splits the sound going to the center channel, with the lower frequencies being fed to speakers on either side of the screen and the higher frequencies going to a speaker above the listeners’ heads and aimed at the video wall, so they bounce off and seem to come from close to the middle of the screen

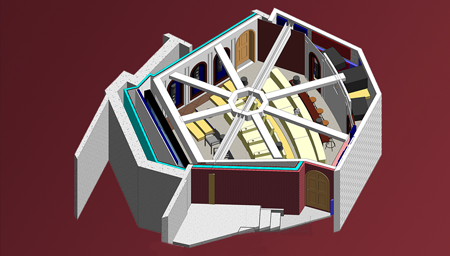

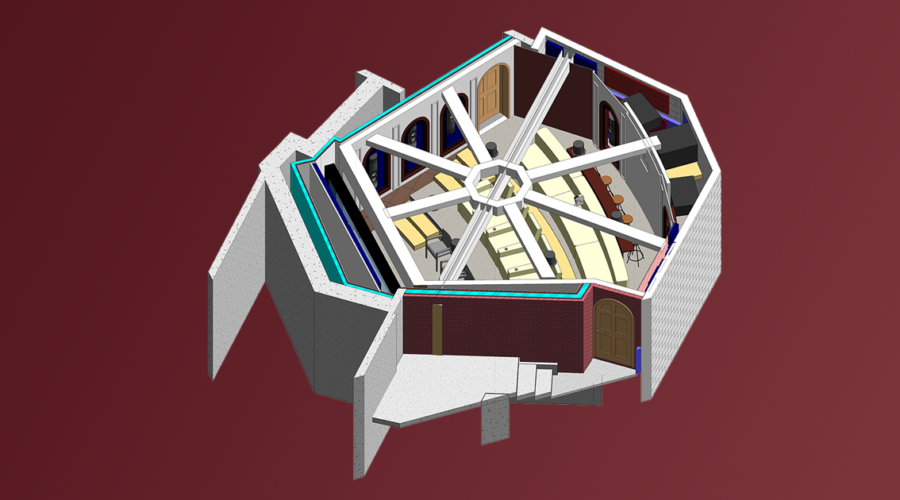

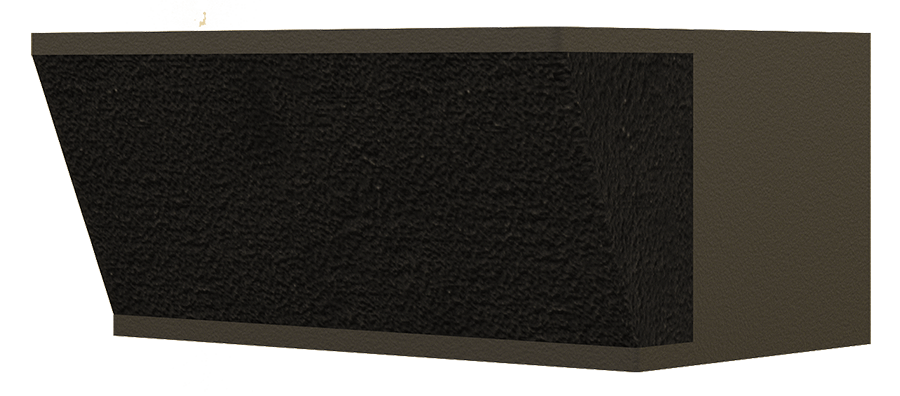

Renderings of the Conic Section Array waveguide, shown with and without a speaker grille. The waveguide is positioned in the ceiling to aim the higher-frequency sounds at the video wall, to then be bounced back to the listening positions in the theater.

screen but instead of right behind the screen, it’s 10 or 12 feet behind the screen. If a speaker is right at the screen, you can move back and forth and the speaker doesn’t appear to move. If the speaker is 10 feet behind the screen and you move off-axis—

There’s a little parallax.

Exactly. So the image of the character speaking onscreen does move with you, but just a little—just to be perfectly clear. I believe in telling the whole story. But I think it’s an acceptable compromise. None of this is as perfect as a speaker behind an acoustically transparent screen. Every alternative has its compromises. It’s about finding the right solution with the fewest compromises. And a lot of times, that’s going to be room-dependent.

Are you installing this solution yet or are you waiting for the patent to be approved?

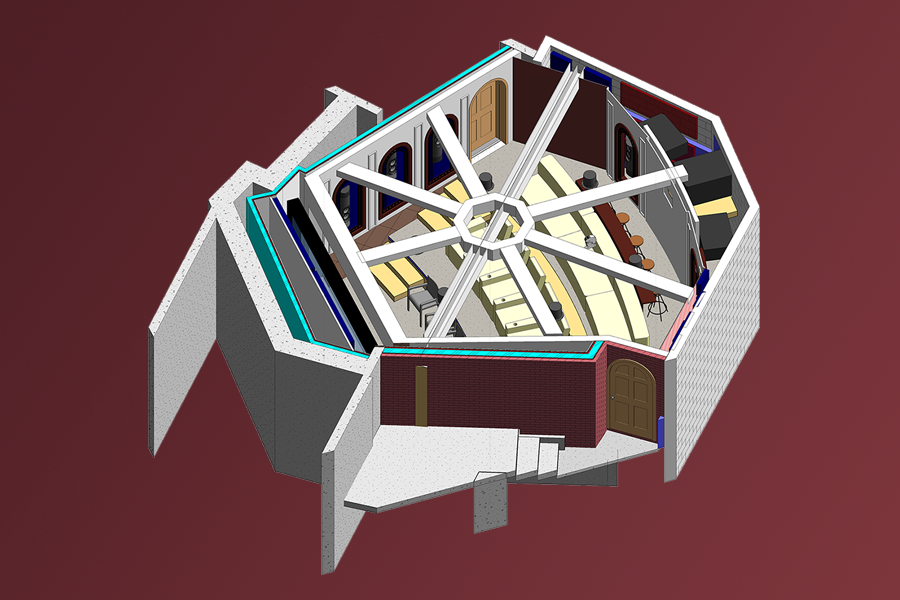

We have it installed in our demo room. In the world of patents, you have to show you’ve reduced the invention to practice. A patent can be shown to be invalid if the only thing you’ve filed in the patent is an idea you’ve never tested. So don’t patent ideas—patent advancements of the state of the art that you’ve proven to yourself or others works. So we have it working here, and I’m working with an integrator in the Los Angeles area to install it on their big LED wall.

So, you said you’re high-pass filtering the signal going to the ceiling center speaker at 800Hz and sending everything below that to the front speakers. Why 800Hz? That’s not a number I hear people reference when they’re talking about directionality of sound.

Yeah, human hearing has very good localization from about 500 or 600Hz up to about 3kHz. That’s sort of the peak of frequencies you can localize, that you can point at and say, “That sound is coming from right there.”

Below 500Hz, the wavelengths get longer and longer, and your interaural gain—the thing that allows you to localize a sound in 3D space even though we only have two ears—gets fooled because the wavelengths get bigger. You know, a 500Hz wavelength is a little over two feet wide. So, your head is, what, 7 or 8 inches? And when a wave is so much bigger, it’s harder to compare the wavefronts coming from one direction versus another. And as you go down in frequency, it gets harder and harder to point to where a sound is coming from.

In the upper frequencies, a 3kHz signal has a wavelength of just a few inches, maybe half the size of your head, so as you go higher and higher in frequency and the wavelength gets shorter and shorter, the obviousness of correlation between the patterns hitting your left or right ear gets more scrambled because it’s smaller portions of what you’re hearing. And so, above 3kHz or 4kHz, your ability to point toward the source of a sound is also increasingly diminished.

The peak of directionality is from around 500Hz to 3kHz, so if you can take the waveguide down to 500Hz and phantom-image everything else, no problem. But that would be a waveguide that’s much bigger, if you really want good pattern control. It’s just not as practical.

So you go, “What if I try 600? 700? 800?” Somewhere around 800 or 900 is sort of this tipping point where the waveguide is practical and you’re definitely starting to hear more in terms of directionality. That’s not to say it’s the best frequency, it’s just a good compromise between practicality and effectiveness.

We have played with 1000Hz, and if the filters are steep enough and things are controlled enough in the room, you can make it work. And that’s a waveguide that’s about six inches, which is really easy to conceal in a ceiling above the sheetrock in the rafters.

At any rate, if the horn or waveguide is designed correctly, you’re not going to hear any direct energy from straight overhead. Mind you, we’ve seen solutions that involve PA speakers laid on their side, shoved way up close to the screen, and they bounce it off the screen from just a few feet away. That’s just too far forward, because if you look at the specular reflection, that bounce is way too high. It misses the screen most of the time. Also, that speaker playing full-range has a lot of off-axis spill starting at around 1kHz or even a little higher, so you’re hearing the sound directly from that cabinet before you hear the reflection.

I’ve talked to Steve Haas about his experience with such systems. In fact, he wrote an article about it for Cineluxe.

It doesn’t work. It just sounds fuzzy and the dialogue isn’t clear, and it clearly doesn’t sound like it’s coming from the screen, which is the entire point.

Basically, the rule is: With a waveguide or horn—or directional beam-steering array, because that’s also in the patent—there’s a frequency at which you need to roll off and go to a speaker that’s at the front of the screen, otherwise your brain goes, “Oh! I hear it coming from up there.” And you know what? It doesn’t necessarily have to be front left/right phantoms. In the patent, we talk about the fact that it could be just a woofer below the center of the screen, right in the middle. The reason we use the left and rights is because they’re there. Why not use them?

Let’s say you’re doing the sound system in a room for which you’re not the designer and you’re having to work with someone who isn’t willing to budge on aesthetics—what considerations come into play then with a setup like this?

The nice thing about this is that it doesn’t occupy any space at the proscenium. It occupies space somewhere in the ceiling, where we need an acoustically transparent boundary of some sort. And so in the beginning of the design phase, we need to say, “There’s a space up there were we either need a grille or some kind of structure that has fabric and wood and whatever, or a printed fabric that replicates the surrounding materials.” It’s a good way to tackle the aesthetic thing because it’s concealed in the ceiling and functionally invisible. As long as you’ve got the space in the ceiling, it doesn’t have to be a box hanging down like an old projector. In a home theater, more often than not you don’t want a thing hanging up there. That’s ugly.

Bouncing sound off a video wall from a ceiling-mounted speaker creates the impression the sound is originating from a point behind the screen equal to the distance from the speaker to the screen.

“The nice thing about this solution is that it doesn’t occupy any space in a home theater’s proscenium. The waveguide occupies space somewhere in the ceiling instead.”

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC