Theo Kalomirakis: A Personal History of Home Theater, Pt. 1

The man who started it all on how his desire to see favorite films at home transformed movie-watching forever

by Michael Gaughn

January 7, 2022

Because he’s the guy who invented home theater and remains beyond doubt its preeminent designer, people tend to assume Theo Kalomirakis’ interest lies primarily or solely in the design side of things. And if you only know his reputation or his work but not his history, that’s a natural enough assumption to make.

But digging a little deeper goes a long way toward explaining why, despite all the changes in technology, entertainment, and taste over the years, Theo’s theaters continue to be the most evocative and compelling expression of the idea of watching films at home. The explanation—which really isn’t a secret, just obscured by the dash and brilliance of his designs—is that everything he does springs from his unusually deep passion for everything movies.

Theo is an accomplished director, a graduate of NYU’s legendary filmmaking program whose work has been screened at such high-profile venues as the New York Film Festival. He’s also accumulated one of the largest private movie collections in the world—maybe the largest. The theater he recently built at his home in Athens, Greece has become a mecca from everyone from students to critics to directors and other film-industry professionals.

All of this, and his constantly restless spirit, which keeps him from ever doing the same theater design twice, helps make clear why he’s been able to create a body of work that will likely never be equalled, let alone surpassed.

In the series of interviews that follows, Theo provides a snapshot of each phase of his career, dipping into the past not so much to reminisce as to show the continuing relevance of the core ideas that have driven his designs. At a time when home theaters are going through a tremendous resurgence—especially at the highest end of the market—fueled largely by the pandemic-driven desire to have domestic retreats from the world, Theo’s efforts provide fertile ground for conceiving new ways to create unique and captivating movie-watching spaces within the home.

—M.G.

Because you had such an intense interest in movies, you started cobbling together systems before you even thought about designing theaters.

Absolutely.

What was the state of the technology when you started doing that?

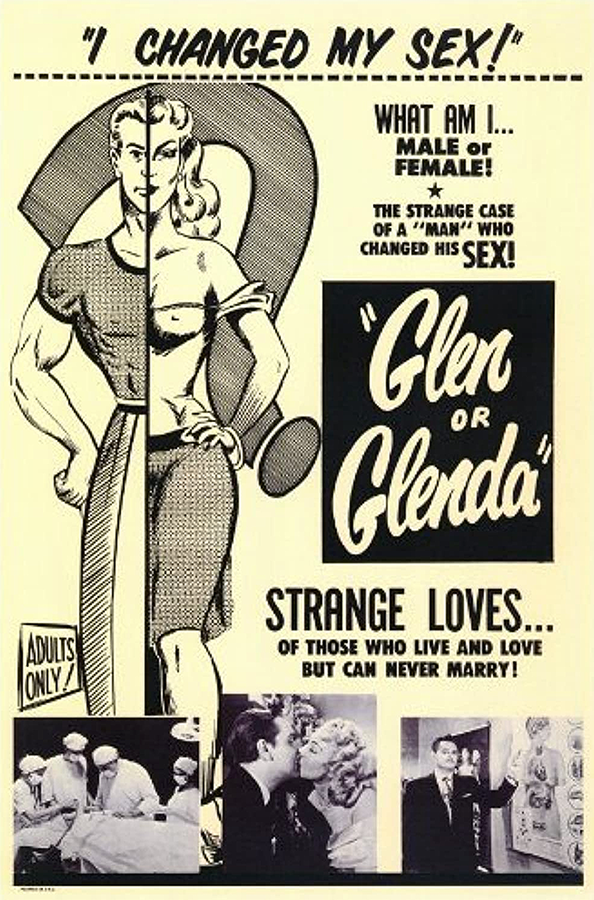

My first glimpse of something coming was in 1981 while I was working as a graphic artist at the Abraham & Straus department store in Brooklyn. I went down one day to the electronics department and saw an exhibit of LaserDiscs. It piqued my curiosity because I already had started buying videotapes of movies. Before that, I would spend nights recording them off TV, waking up during the commercials so I could pause the recording and start it again when the movie came back on. The very first Betamax tape I bought was Glen or Glenda. It’s a bizarre choice, but it was good to see a movie that you could hold and have. The second one was A Star Is Born, with Judy Garland, which actually had stereo sound, which was a revelation. But it was cropped. The first version of every movie that came out on videotape was cropped.

What were you watching your tapes on?

I had a 19-inch Sony Trinitron monitor with two Klipsch speakers. Then one day I went to New York Video, where I saw this big TV—a Mitsubishi two-piece, where you opened the front and the three beams projected into a mirror from under the screen. I fell in love with it and bought it on the spot. It was a floor model, so I could afford it. I set it in the middle of my living-room window, which was the death for me of watching movies in my apartment because it blocked half the view and the sunlight would come in and wash out the movie, but there was no other place to put it.

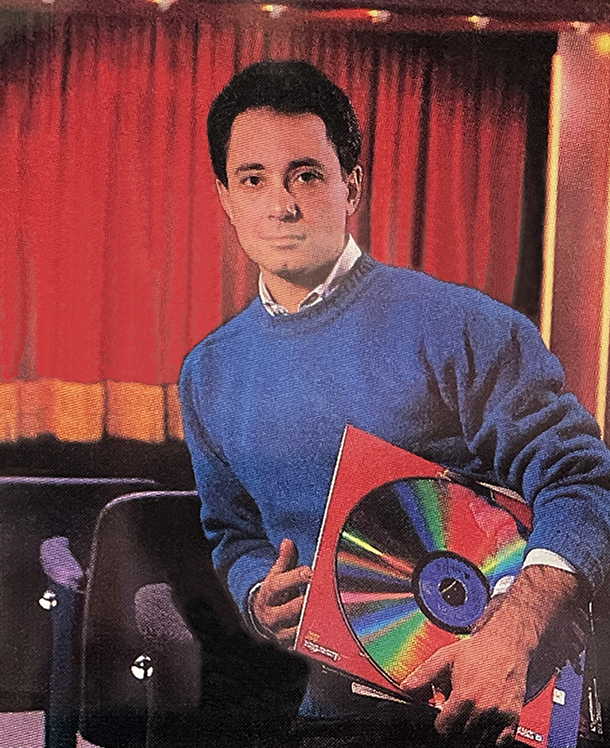

I connected my Betamax to the Mitsubishi and played A Star Is Born, but the picture was fuzzy. So I went back to the store the same evening and said, “What you sold me is not what I saw. It has a defect and I need to give it back.” And the owner said, “You don’t know what you’re talking about. What are you playing?” I said, “A Star Is Born.” He said, “What you watched here was a LaserDisc. You saw a sharper picture because of the source.” So I said, “Give me a LaserDisc player and add a Raiders of the Lost Ark.” I didn’t hesitate because I was enthralled by the sharp pictures. So I took it home, and that was the beginning of my obsession with LaserDiscs

I took the Klipsch speakers—I don’t remember where I got them, but they were big—and I put them left and right of the TV and took advantage of the stereo sound. It was sensational. That’s why people would applaud. They were watching for the first time with a big picture and big sound. They would come and gather around and we would watch movies very religiously without distractions—except for the distraction of the environment, which was a major letdown for me.

What led up to you creating your first home theater?

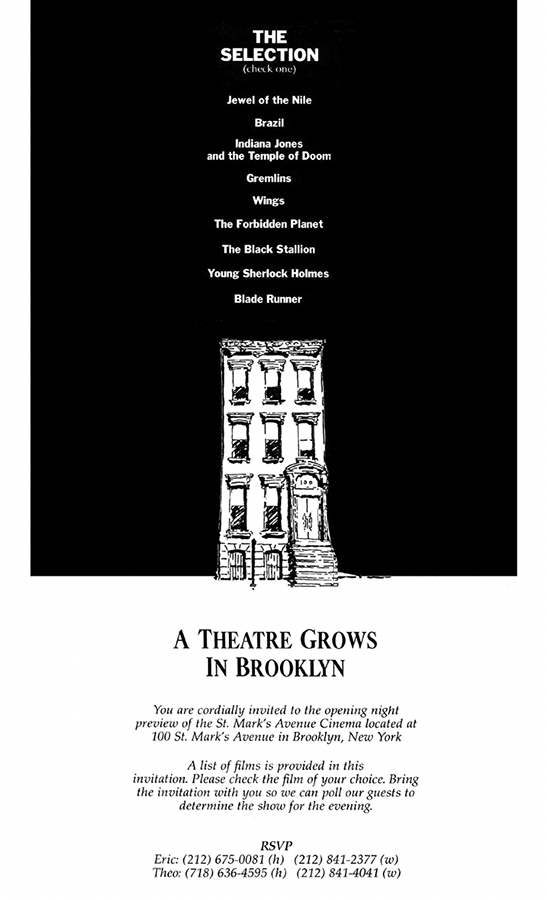

In 1983, I found a brownstone on St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn that had a basement so I could have a better place to watch movies. But I was very disappointed. The TV had looked big enough in my living room but looked too small in the basement. So I wanted something bigger. Someone had told me Barco was selling a bunch of projectors that had been in TWA planes. So I got one—I remember I paid, like, $600. I bought a screen from a photo-supply store. It was no more than a hundred inches but it was big enough. The room was small. It fit the space.

It fulfilled my goal to have a a dedicated room with a big screen and no windows. I painted everything a consistent color and upholstered the seats. But suddenly the fact that I had sewer pipes running over my head, and drop-ceiling tiles, was like anticlimactic. I thought, “This is not really cutting it.” I started looking at pictures of theaters but I hadn’t really spent too much time studying their architecture. But the buzz about home theater was already beginning because I still have the story that appeared in USA Today with me holding a bowl of popcorn at the 100 St. Marks theater.

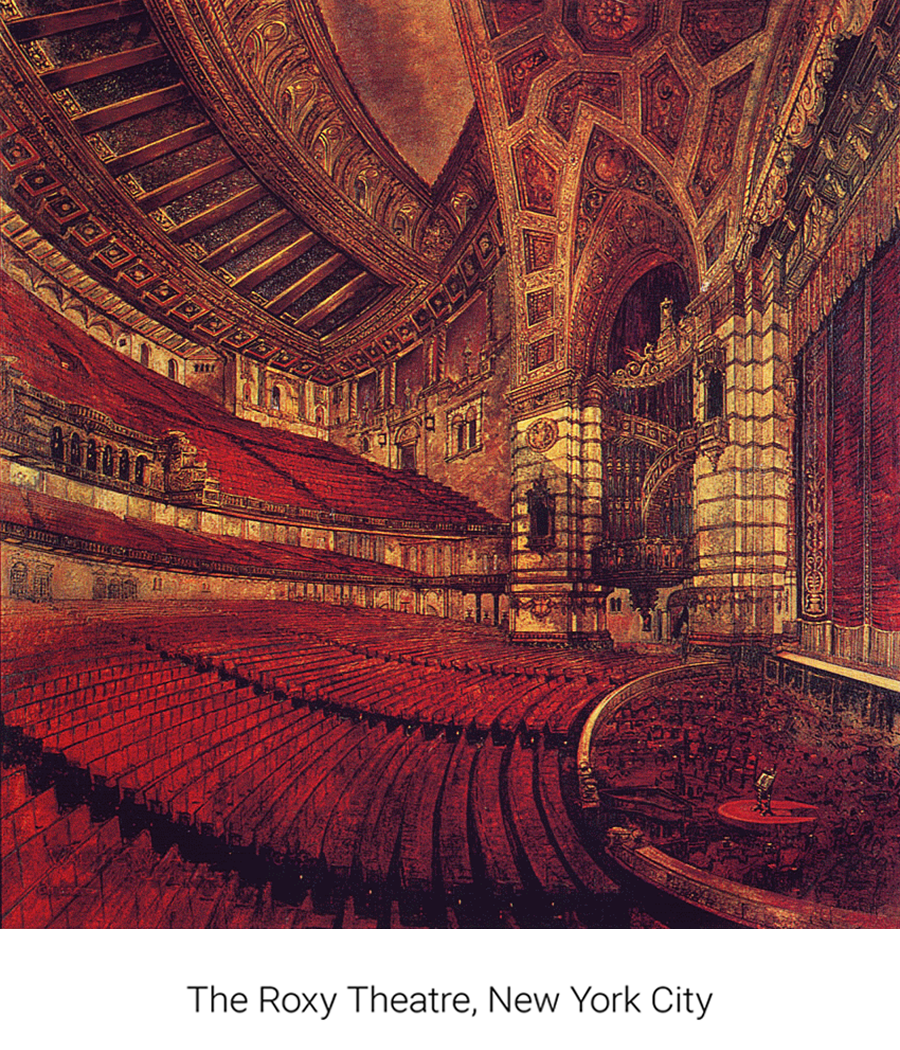

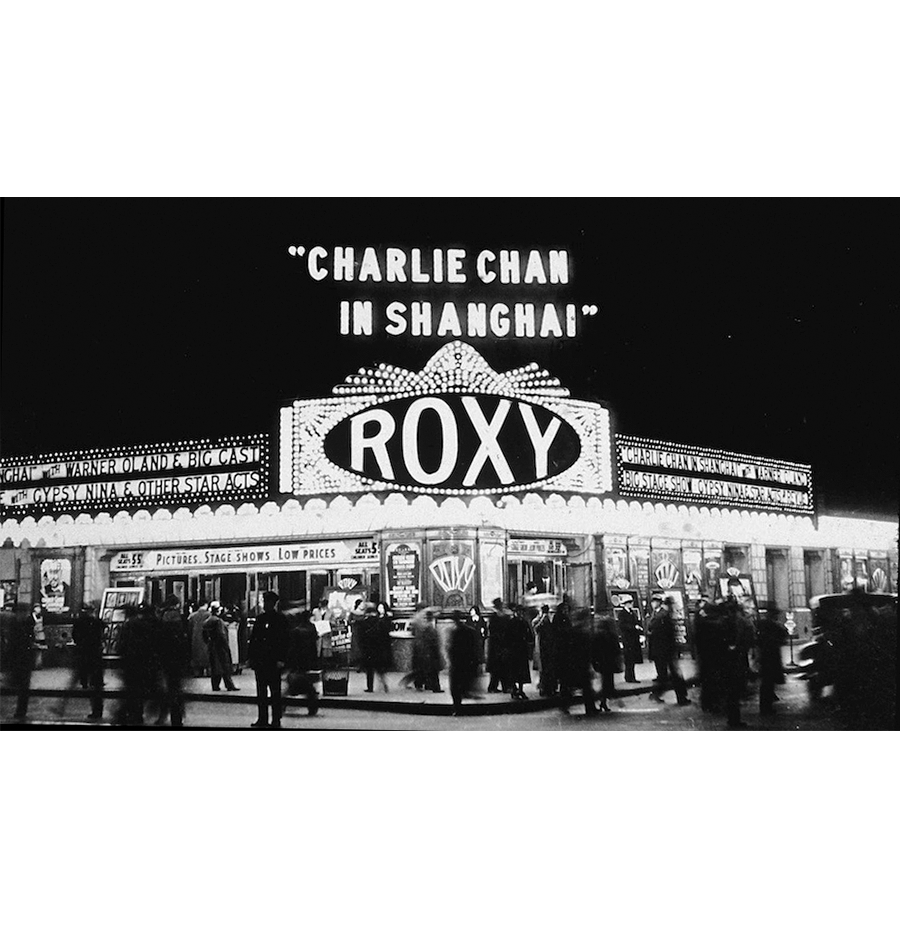

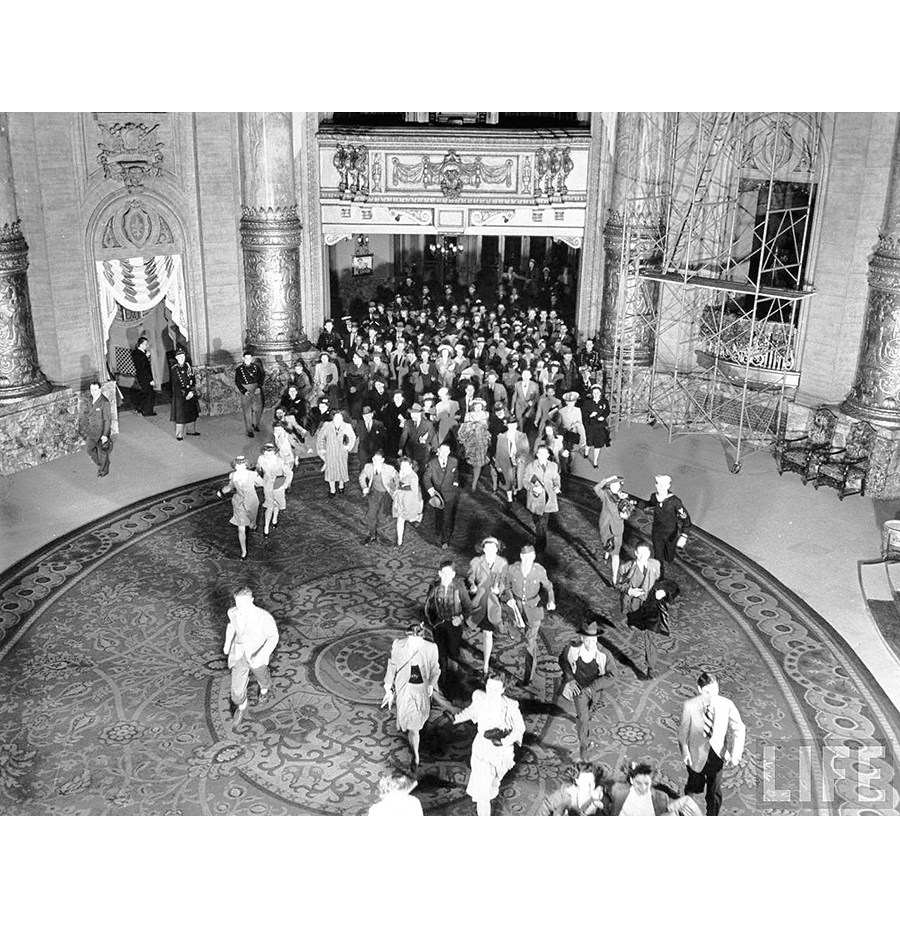

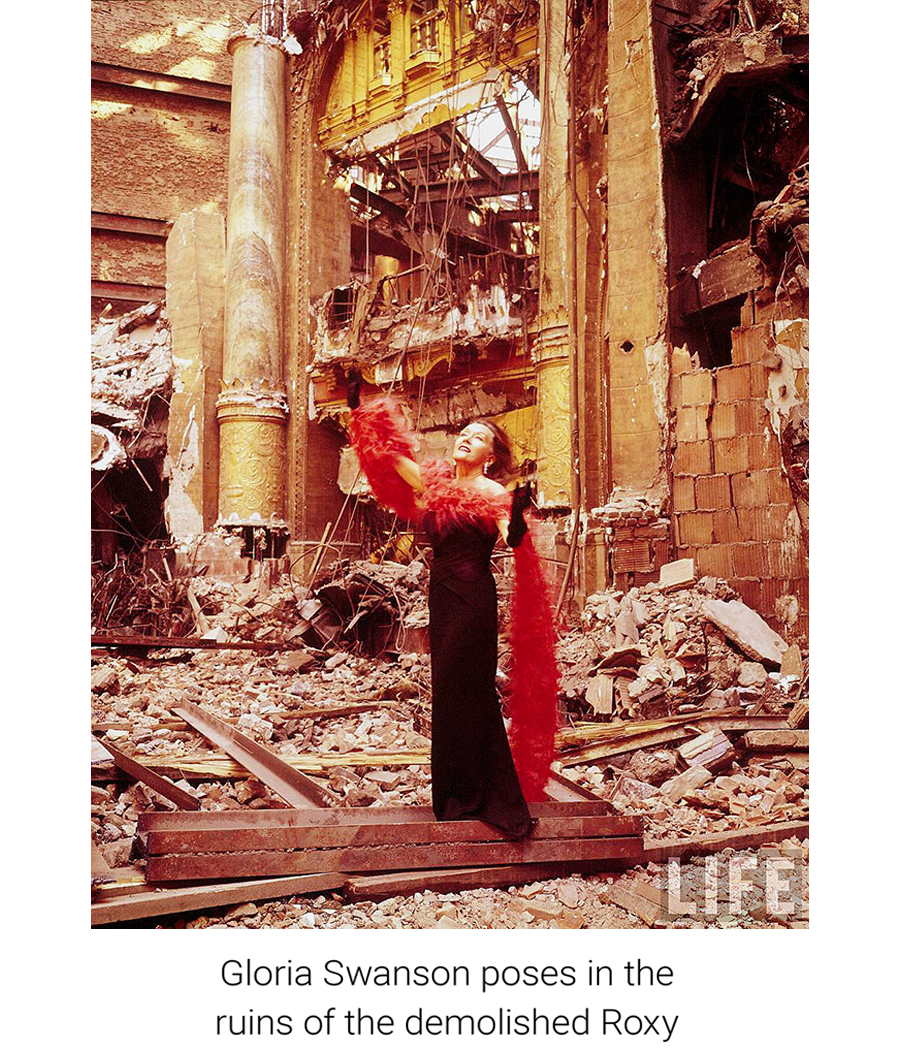

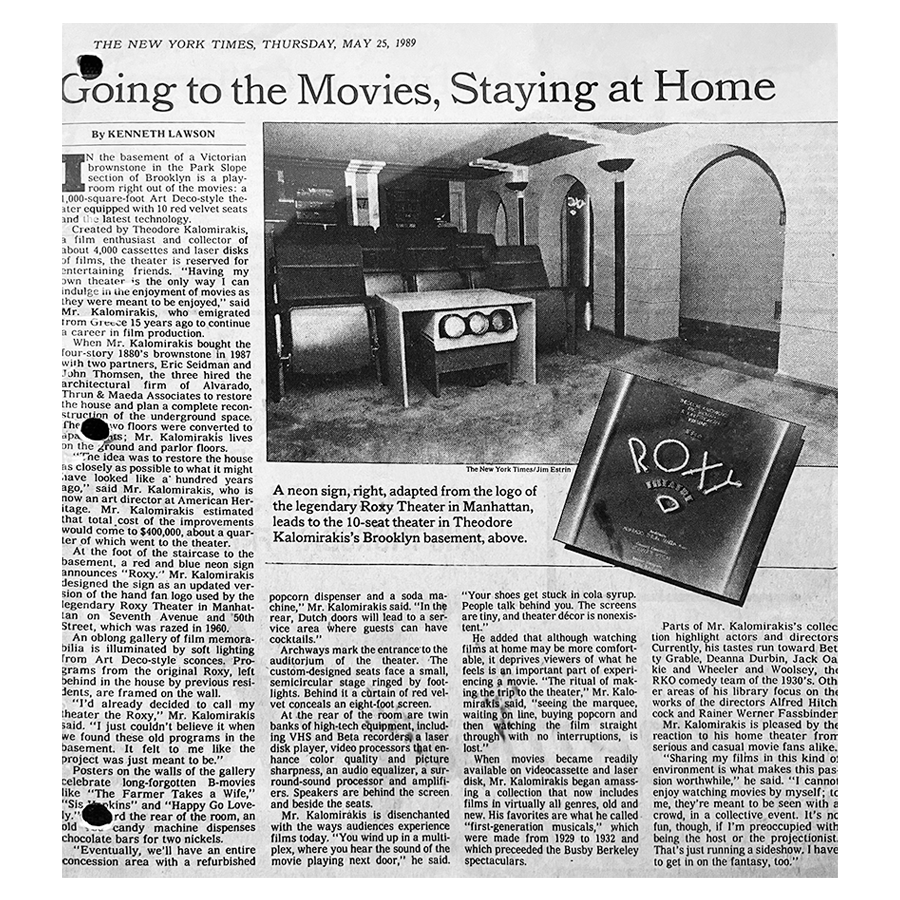

I knew my theater needed something else, though, so in 1985 I bought a townhouse on Union Street in Brooklyn where I knew I could do something something better, something that was more grandiose. I had discovered pictures of the original Roxy Theatre, and there was a big model of it at the Kaufman Astoria studios in Queens.

How deep was your interest in movie palaces before you did this?

I would say there was no interest because there was no knowledge. But something strange happened. The lady who had lived on the first floor had been married to the last projectionist of the Roxy. And I found in the basement, in a box, wrapped up, some valences from the curtains for the balconies and a whole bunch of programs. And there was a key to a projection room, which I found out later was from the Loew’s Kings on Flatbush Avenue.

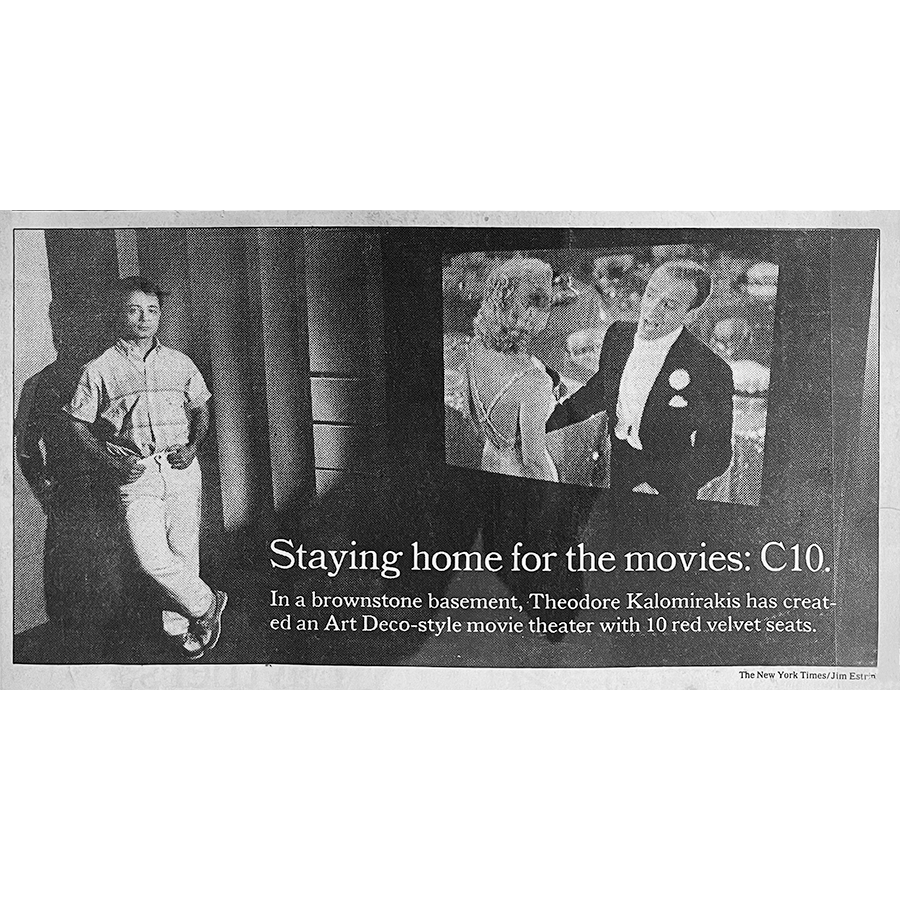

While I was finishing my theater, which I called The Roxy, I started immersing myself in books about theater architecture. I hired an architect to help me do the theater. I kept the arches of the basement as a design element. But the big difference between this room and St. Marks was that it had an outer lobby with a marquee. And immediately I started promoting it, or it promoted itself. I don’t know what happened.

Did you upgrade your system as well?

Yes. I had seen a 70mm film at the Ziegfeld in Manhattan and I was entranced by the sound. So I went to the projection booth and became friends with the projectionist, Mike Percoco. He took a liking to me because I was nosy. He took me backstage and showed me the big horn-loaded JBL speakers. I said, “That’s what I want.” Now, it was chutzpah to want these huge speakers—the same ones that were in the Ziegfeld—in a tiny room. I didn’t care. I thought, “These are the speakers that can do that sound. These are the speakers I should have.” That was a very important connection with Mike because it led to the theater being a guinea pig for new technologies.

Later he said, “You know, there’s something new coming and it’s called ‘surround’.” The first processor that came out was called Sensurround. Bob Warren from Dolby flew from California, saw what I had, and said, “I’ll give you what you need.” So I got free a Dolby surround decoder. I then bought four more JBL speakers for the sides—not in the back. Two and two, flanking the three rows of seats.

It seems like it’s never been just a design thing for you, that you were also trying to make sure you were on the cutting edge with the technology.

Absolutely, absolutely. Technology is important. Without it, you get stuck with just a nice-looking room—if it is nice. To your point, I was always chasing the latest technology that was produced.

That takes us up to 1986.

Nothing much happened from then until 1990, when I got my first commission to design a theater—the Sweet Potato on Long Island.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

The first glimpse many people had of home theater was via Theo’s The Roxy on Union Street in Brooklyn, shown here

c. 1986. (Roxy photos by Phillip Ennis)

related features

Theo with his LaserDiscs

Theo (far right) at his first home theater on St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn

Theo’s first coffeetable book, Private Theaters, includes more about his early work

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC