Ask anyone who engages in film criticism online if they want their reviews included in the official Rotten Tomatoes aggregate score. If they tell you no, they’re lying.

But why? What’s the value in having your thoughtful analysis reduced to a number, added to a total, divided by whatever, plastered on advertisements, and tacked onto the listings for online film retailers as either an enticement or a warning?

The sad truth is that Rotten Tomatoes is the only source of film criticism most people pay attention to these days. So unless your unique perspective is thrown into this particular salmorejo pot and boiled down to mush, your voice isn’t contributing to the discussion about any given film in any meaningful way as far as most consumers are concerned.

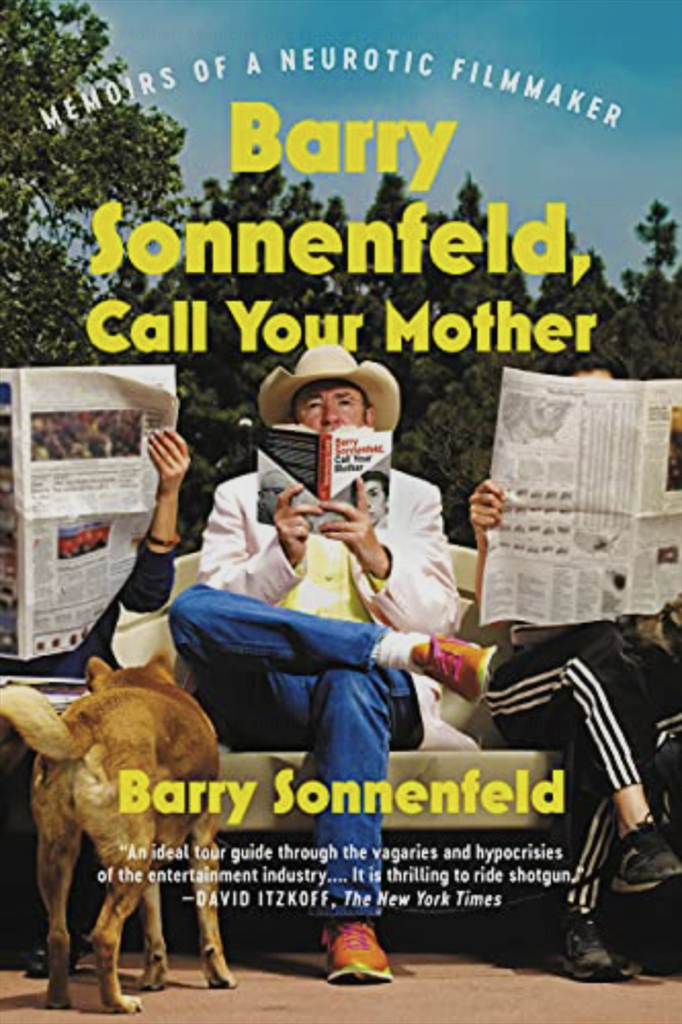

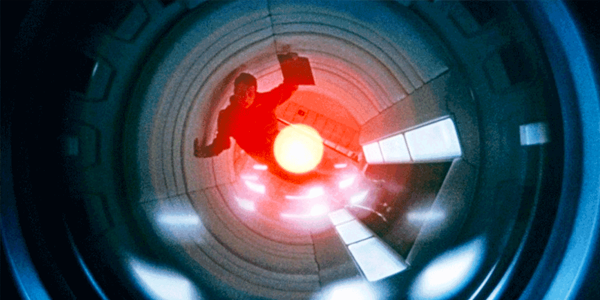

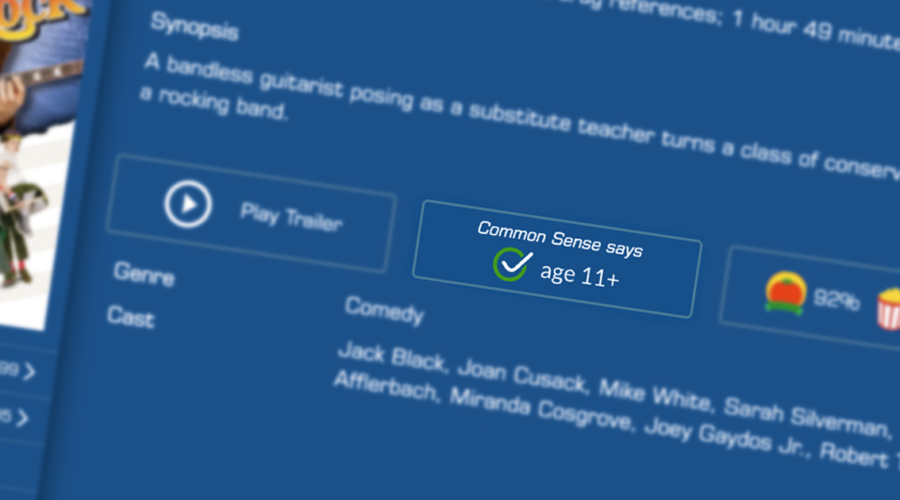

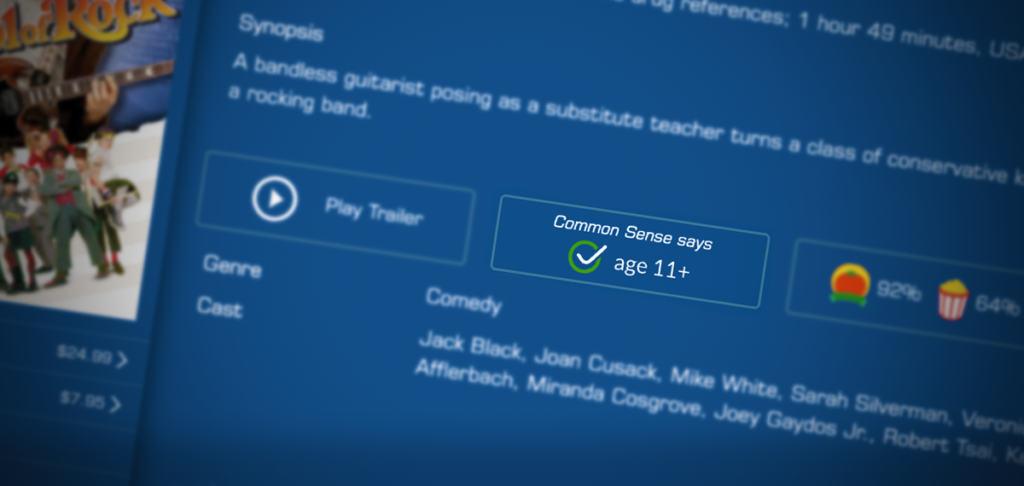

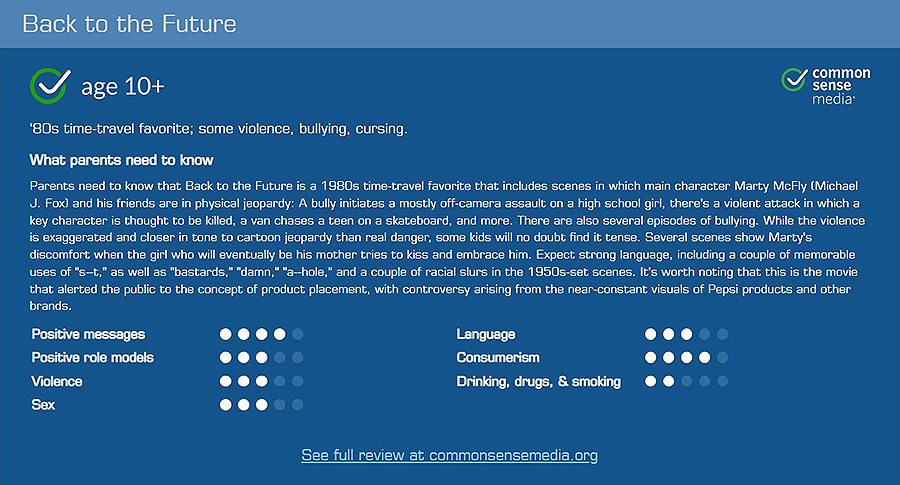

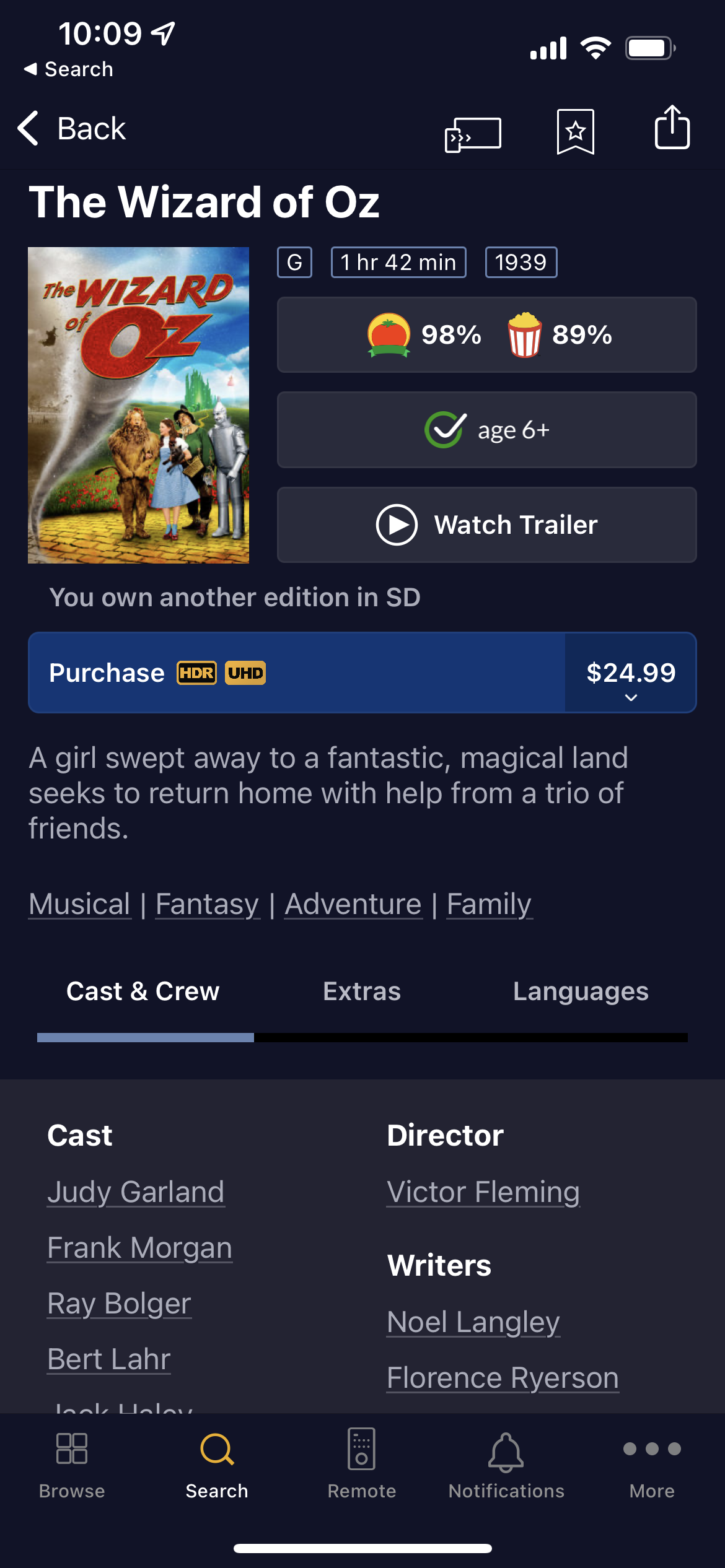

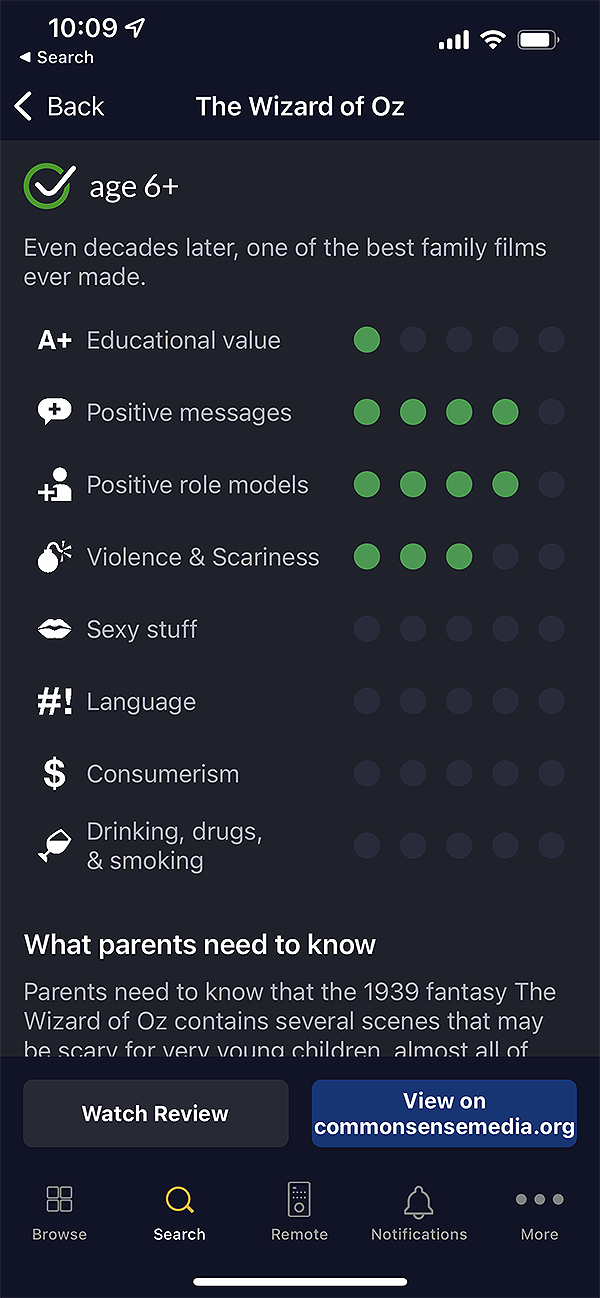

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t actually think there’s anything fundamentally wrong with the service Rotten Tomatoes provides, at least not in principle. The handful of other film reviewers whose work I actually read (and it is a tiny handful), I discovered via RT after having a “Fresh” score for a film I loathed shoved down my throat by Vudu and iTunes and even my beloved Kaleidescape, and I turned to the aggregator for some perspective on why it was so well received. Or, conversely, when a film I was seriously interested in got bombed with a “Rotten” score and I wanted to explore further to see if there was any substance to the criticism or if it was largely politically motivated.

I wouldn’t have discovered my favorite modern film critic, Mark Kermode, had I not waded into the shallow waters of Rotten Tomatoes to discover why House of Gucci—an abomination I described as “the worst movie I’ve suffered through since 1993’s Super Mario Bros.”—was “Certified Fresh.” And let it be stated for the record that I don’t agree with the three-fifths compromise of a score Kermode gave the film, but this line from his conclusion, linked from Rotten Tomatoes, at least gives me a sense of what he saw in it: “[F]or better or worse, House of Gucci is a little too well behaved to become a cult classic. But Gaga deserves a gong for steering a steely path through the madness.” Hard to argue with that, and I think I’ve read everything he wrote since, despite the fact that I disagree with his conclusions more often than not.

But is that really the way most people use the site? I think not. Which is a roundabout way of saying Rotten Tomatoes isn’t the problem; the way society at large uses it is the problem. Is it really so surprising, though? Turn your attention to the largest discussion forum in the world, Reddit, and you’ll find post after post that begins with a sheepish “What’s the consensus on . . ?” when the topic at hand is a purely subjective consideration, a matter of personal taste. And every time I see a social media post that’s addressed to “The Hivemind,” I want to yeet my smartphone into the sun.

Individual expression—indeed, individual thought—seems verboten these days, so of course a service like Rotten Tomatoes has become the opiate of the masses. The problem for independent thinkers, though, is that if your contribution to the discussion at large can’t be chopped up and bundled like mortgage-backed securities that are repackaged into collateralized debt obligations, it seems to be of no use to the groupthink-driven pop culture machine.

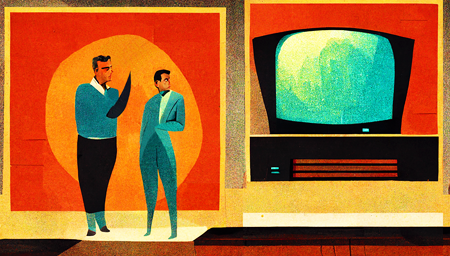

Of course, it’s impossible to talk about groupthink without acknowledging that there always seem to be two groups doing their collective thinking, one “fer it” and one “agin it,” no matter what “it” is. As a sort of tech-obsessed dweeb with a background in the fine arts, I am of course fascinated by the Generative Adversarial Networks that are in the headlines so much these days. In fact, I used one of my favorite text-to-image neural networks, Midjourney, to create the image you see at the top of the page. And that fact alone will delight some of you and outrage the rest.

Generally speaking, most of the people who are outraged are outraged for the wrong reason. They’ve been told these neural networks are stealing the work of others, copying and pasting elements of different images to create what the user asks for. They don’t work like that, though. They’ve simply been trained on enough images that they know what a tomato looks like, they know what a cinema looks like, they know what makes a painting look different from a photograph, and they can synthesize images in a variety of different styles based on the words you plug in (although, these days, most users have outsourced any thought they used to put into their prompts to language-based neural networks like ChatGPT). There are some living artists who don’t want their work included in the training data, and I fully support them, if only because having an AI being able to spit out images that could easily be mistaken for their work does cut into their potential revenue stream.

My thoughts on all of this fall somewhere outside the Overton Window that defines the two opinions you’re allowed to have about artificial intelligence. I think it’s fascinating and a real boon to writers like myself who can’t afford to pay an illustrator yet still want our articles to be visually engaging.

I also think these neural networks represent a legitimate threat. But it’s not the services themselves that actually pose the threat. It’s how we use them. And the fact that humanity as a whole seems to have decided that an aggregated average of thumbs ups and thumbs downs says anything meaningful about the quality of a film only reinforces those fears.

In my review of Everything Everywhere All at Once—without a doubt the best film I’ve seen this century and one that most of my acquaintances didn’t bother to watch until the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gave them permission to do so—I bemoaned the fact that our “metaphors have lost all meaning. Our totems have lost their functional connections with the things they’re supposed to symbolize and have taken on disproportionate importance on their own. The trappings have come to be the entire point.”

All of this feels like a manifestation of the same dark and soulless trend. Text-to-image neural networks are derivative by nature. They are not in any sense creative. They can only remix what has come before, and they only pose a threat to actual artists if we allow them to. And if they do put living, breathing artists out of work, these text-to-image generators will stagnate because there will be nothing new to amalgamate.

Isn’t it the same with Rotten Tomatoes? If you’re using it to help you cut through the noise and find meaningful film analysis that resonates with you, that’s great. That’s how it ought to be used. But you’re probably not, are you?

If not, consider this: If enough of us stop reading film criticism and just rely on that one idiotic, meaningless spandrel (or two, if you consider the even more politicized “audience” rating) to inform our viewing decisions, and if publications stop paying for film reviews as a result because nobody reads them anymore, where will your Rotten Tomatoes score come from then? Two angry mobs using review-bombing as the new frontline in the ongoing culture war?

No thank you.