When Barry Met Sally

when barry met sally…

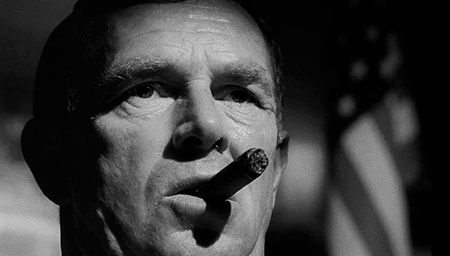

Always irreverent, filmmaker Barry Sonnenfeld offers his thoughts on the 4K release of the classic 1989 romantic comedy he shot for director Rob Reiner

by Michael Gaughn

October 20, 2022

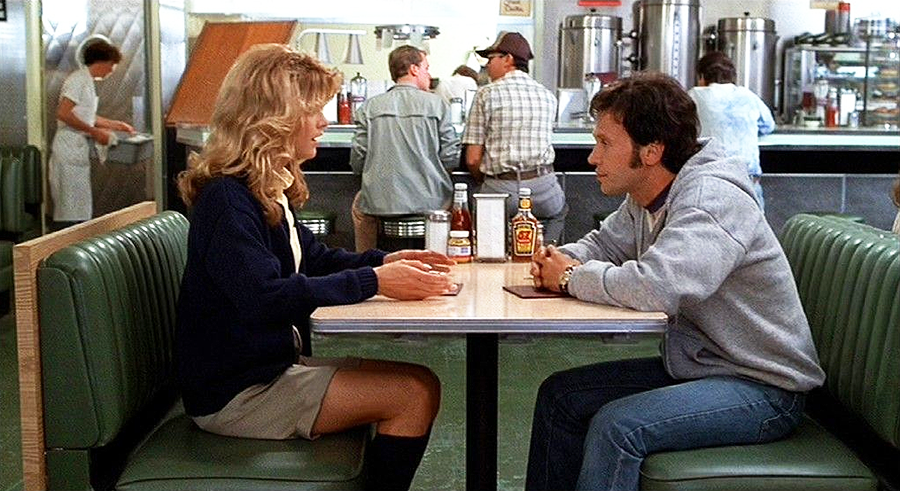

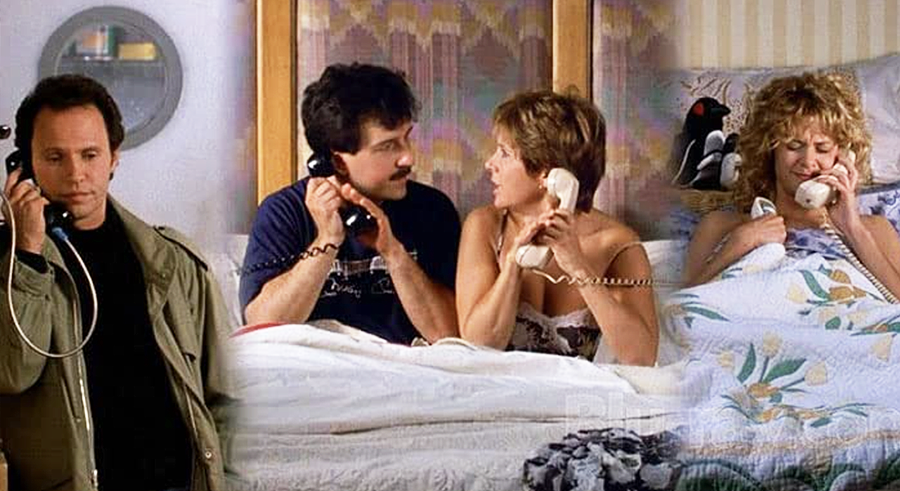

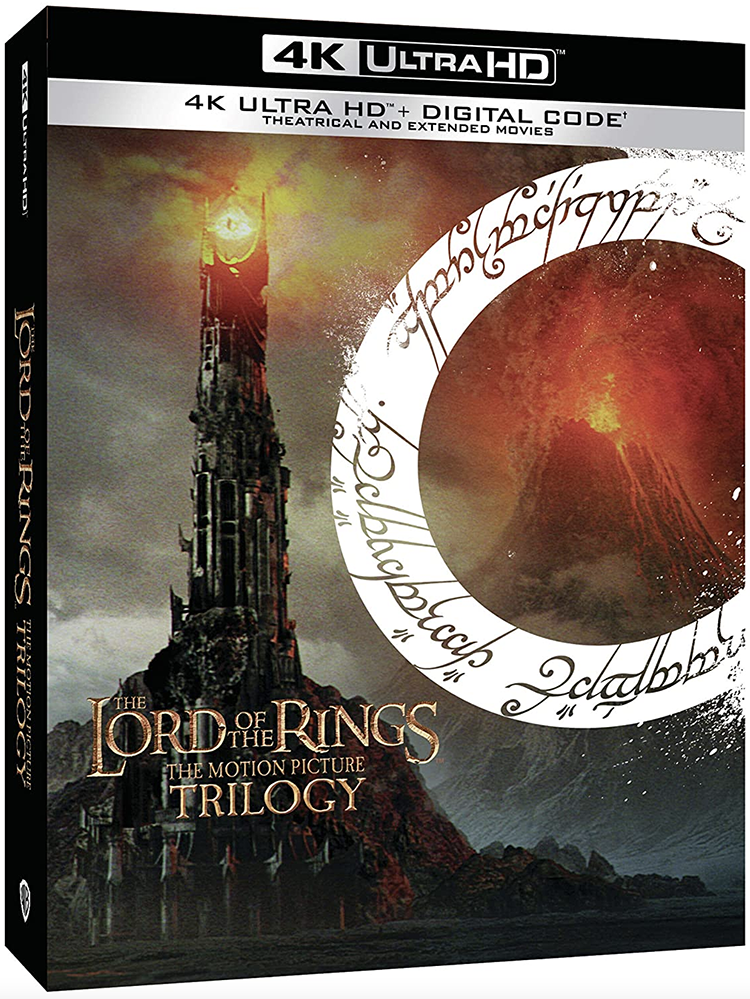

Before he was the director of such iconic movies as Men in Black, The Addams Family, and Get Shorty and of groundbreaking series like Pushing Daisies, The Tick, and A Series of Unfortunate Events, Barry Sonnenfeld was a much sought after cinematographer whose credits include the early Coen Brothers movies and such hits as Big, Throw Momma from the Train, Misery, and the film considered here, When Harry Met Sally… . After watching the recent 4K release of the classic Rob Reiner romantic comedy, I was curious to see what Barry thought of the new transfer. As always, he was beyond generous with both his time and his comments, and not shy about saying exactly what was on his mind.

Barry on 4K and HDR

“The problem with some of the new tools available to electronic cinematography is that they’re more marketing than necessarily aesthetic choices. For instance, 4K doesn’t necessarily give the viewer a better experience. All the major streamers insist on shooting with 4K equipment but truthfully every pore on an actress’s face or every line of makeup is visible in 4K. So what what we often do is soften or reduce the resolution of the 4K camera by using old non-coated lenses or by putting filtration in front of the lens. So, yes, in theory you’re filming in 4K but we are doing everything in our power to make the image look like HD, or 2K.

“It’s the same problem with HDR. On A Series of Unfortunate Events, we were asked to release the last two seasons in HDR. But HDR took our beautiful muted, low-contrast, low-saturation image and—as per its name, ‘high dynamic range’—would increase our perfect and designed low dynamic range and brighten the image, adding saturation to the colors, doing what it was designed to do—add dynamic range—which unfortunately made the show less soulful and dreary.”

related review

MGM decided to do When Harry Met Sally… as a straight 4K transfer, sans HDR. How true is it to what you shot?

I was very pleased with how muted the colors were and how unelectronic the 4K transfer looked. I’m thankful that it was not released in HDR. Just because you have that tool doesn’t mean you have to use it. If it had been in HDR, all those colors would have been video-game colors. The reds would have been super saturated, the yellows would have been super saturated. So I liked that there was a soft, non-saturated look to it.

The transfer was very true to the original color timing. There were a couple of interior scenes I would have timed slightly different, though. At that period in my life as a DP, for some reason I had a problem with the color yellow, so a lot of the scenes are slightly—like a point more—magenta than I would have timed them now. When Harry Met Sally . . . , Big, and Throw Momma all tended slightly on the cooler side.

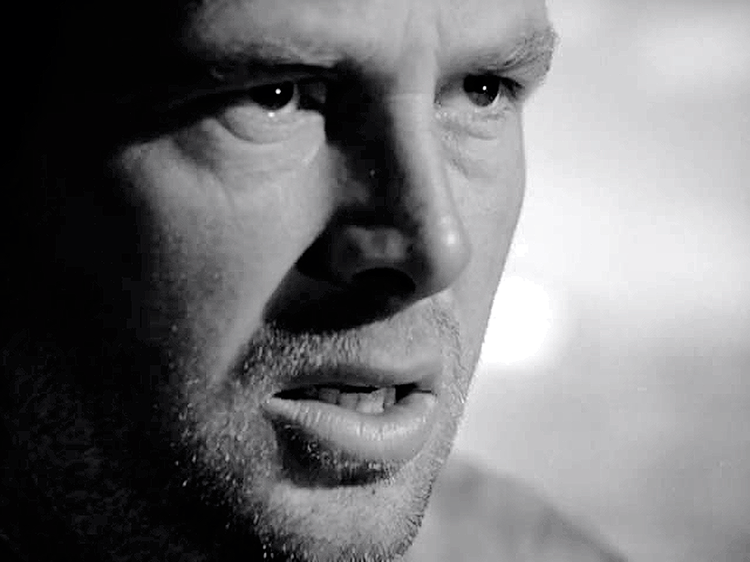

There’s something else I would have done in retrospect. Some of the closeups are too tight. They felt slightly claustrophobic. If I were shooting it now, I would have asked Rob [Reiner] to widen out just a little bit on the dolly to have more breathing room around faces.

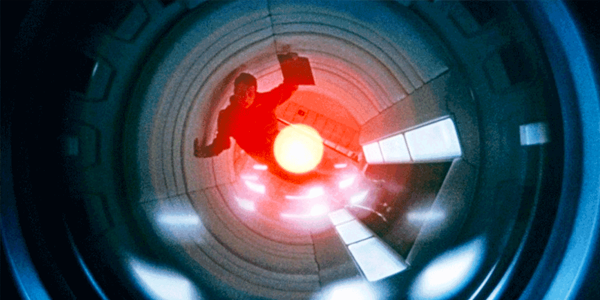

Some HDR versions of classic films, like 2001, look amazing but sometimes an HDR release seems like an opportunity to scrub away grain, screw around with the color palette, etc.—à la The Godfather—and basically create a new version of the film.

I totally agree. I think there should be only one version of a movie. I don’t like special director’s cuts because every time you see one, whether it’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind or the 42 different cuts of Apocalypse Now, they always add stuff. You look at it and go, “I see why the theatrical cut was the way it was.” It was actually the best version. I don’t think there should be seven versions of Picasso’s Guernica, like, “Hey, look—we have acrylics now. Let’s repaint it without oils.” Just because you can improve something—and “improve” is a relative word—doesn’t mean you should.

Joel Coen and I recently worked on rereleasing Miller’s Crossing in 4K for Criterion. During the title sequence, a hat lands in the foreground and then the wind picks it up and the hat flips and flips and goes into the distance and up into the trees, and then the title says “Miller’s Crossing.” Joel and I joked that if we were doing that today, we would have just shot a plate of the background and the hat would have been totally CG. Instead, we had a piece of monofilament tied to the hat that went a hundred yards down into the distance and 80 feet up in the air, where we had it tied to a motor in a cherry picker that pulled the hat.

The problem was, during every take, the hat just got dragged across the ground, got to the base of the tree, and then went up like an “L”. What we ended up doing is—and you can see it if you frame-by-frame that shot—we had three little sticks in the foreground so that when we threw the hat in, it landed in front of the sticks, so that when it then got pulled by the monofilament, the twigs forced the hat to immediately flip instead of being dragged. And that flip gave it aerodynamics, and then it went up into the air.

So I said to Joel, “Now that we’re doing this remastering, should we get rid of the sticks?”— because now it would just be a two-minute electronic thing to remove them. Joel said that he had the same idea but realized we shouldn’t do it, that it’s fun to see if anyone notices the three sticks. I think that these remasterings, it’s great if you can remove dolly tracks—with the Coens, there were always dolly tracks, lights, all sorts of stuff, since I was a terrible camera operator—and it’s OK to remove a microphone that had always been sticking into the top of the frame, but to change the look of the whole show is nuts.

I was wondering if seeing Harry Met Sally again triggered any memories about shooting the film.

There’s that scene where Sally drops Harry off outside of Washington Square Park, with that mini Arc de Triomphe. And on that shot, we pulled up into the air. I got really uncomfortable when I watched that because Rob and I almost died on that crane. We were riding it together to see what the shot was going to look like, and the crane came off the track and teetered. The weights were balancing us and the back of the bucket, and if the crane had completely come off the track, we would have been launched to Asbury Park, New Jersey. Luckily, the crew caught it just as it was going to flip over.

Nowadays, that would have been a Technocrane—no one is riding cranes anymore. Or, it would have been a drone, and we would have gone 10 times further back. I’m not saying it would have been better but we would have shot it differently.

Joel and Ethan and I always joke that if we were reshooting Blood Simple or Raising Arizona today, they would be 10 ten times the cost and wouldn’t be as good. You know that shot in Raising Arizona where we go over a fountain, over a car, up a ladder, though a window, into Florence Arizona’s mouth? We would have shot that totally on a drone in one continuous shot and it would have had a different energy. The fact that Joel and I were running on either side holding a 2 x 12 carrying an Arriflex 2C camera with a 9.8mm Century Optics lens gives it a different feel than if we had shot it on a drone.

Directors feel obligated to work in drone shots now and the shots feel so similar that it’s always obvious they were done with a drone.

I don’t want to sound like an old guy but you don’t want to fix what ain’t broken. And I really feel that these new techniques are fixing what ain’t broken. For instance, in terms of sound—and some people disagree with me—just because you can put certain sounds in the surrounds doesn’t mean you should. I work with Paul Ottosson—three-time Academy Award winner, four-time nominee, for Hurt Locker and other things. He’s done several movies for me and he did all three seasons of A Series of Unfortunate Events. Occasionally he’ll put a knock on a door in back of the room because the person’s going to come in from off camera, and it drives me crazy because it literally takes you out of the movie because the screen is in front of you. That is an affect and a “look what I can do,” but it doesn’t help me tell the story. In fact, it takes me out of the story because I’m looking back to see what that was. My point is, just because you can put sound everywhere doesn’t mean you should. Just because you can use HDR doesn’t mean you should. Because I think it’s hurting the experience of watching a movie.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC