You’ll have to forgive me if I’m a bit tongue-tied. I’ll admit I’m quite nervous to be speaking with you.

Well, I don’t have two heads. Just one.

I know it’s a question you must have been asked a million times but how did you originally become interested in special effects?

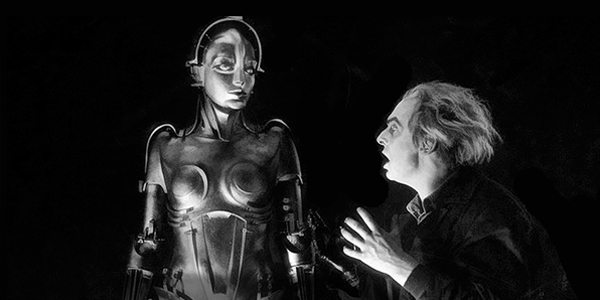

King Kong, when I saw it at the age of 13 or 14, I think it was, at Grauman’s Chinese. I haven’t been the same since. That shows how a film can affect you. It just overpowered me. I had seen The Lost World in the silent days, when I was four or five, because my parents were great cinemagoers, and I had seen the German films—Metropolis and all of those. But somehow Kong, with the music and the sound effects and startling animation, was just amazing.

And when did you start to develop your own special-effects craft?

Well, I started experimenting with it. It took a long time—it wasn’t just “Eureka!” overnight. It took several months before I found out the glories of stop-motion. Finally, it came out in Look magazine and several others, which showed Fay Wray shaking hands with King Kong, and he was small and she was big!

And I started reading about it—there were various misleading articles in Popular Mechanics, assumptions of how the film was made. Very few people knew anything about animation at that time.

What sort of misleading things were they saying?

Oh, one guy said Kong was a great big robot, and it showed drawings of a big mechanical thing walking through a forest, and big cables coming out of his heels and going to an organ, and there’s a little man in the corner playing this organ, and that was supposed to have made King Kong move.

So they were just guessing.

They were just guessing, or else deliberately misleading. They kept it secret how these creatures were made because there was nothing else like them on the screen. And Hal Roach jumped on the bandwagon and made One Million B.C. with live lizards.

With fins on their backs.

Yes, they glued on rubber fins, which bounced occasionally.

Say the name “Ray Harryhausen,” and most people think of those wonderful stop-motion animation models, but your Dynamation process was so much more than that, wasn’t it?

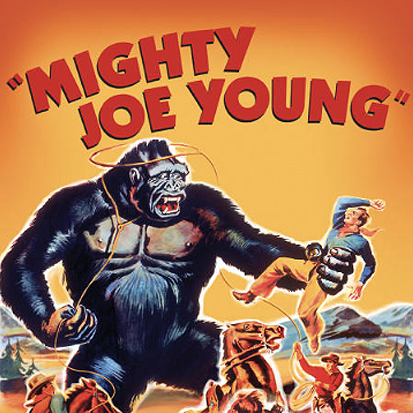

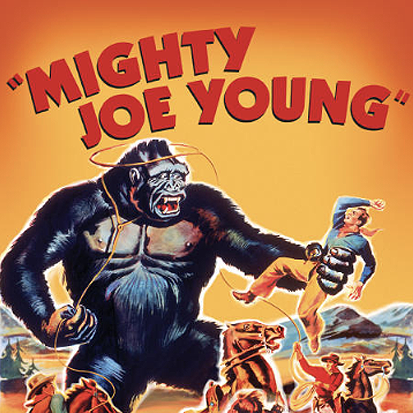

Yes, it was. It was a combination of special photography effects and animation. It was rear-projection mostly, which was the basis of all my Dynamation. When we first released Mighty Joe Young, the critics would say, “Oh, it had animation in it,” and the word “animation” had always been associated with cartoons. So we wanted to get a separate name for this process. Charles Schneer came up with “Dyna-,” because he had a Buick at the time and it said Dynaflow, and we put “mation” on it and made it Dynamation.

You’re kidding. That’s where the name came from? A Buick automatic transmission?

Yes. It was a combination of things because we had to find a new name instead of “animation.”

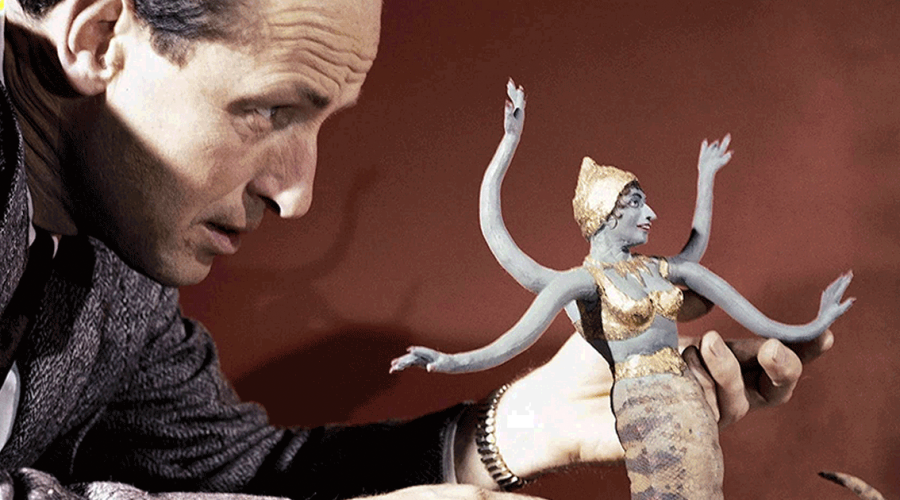

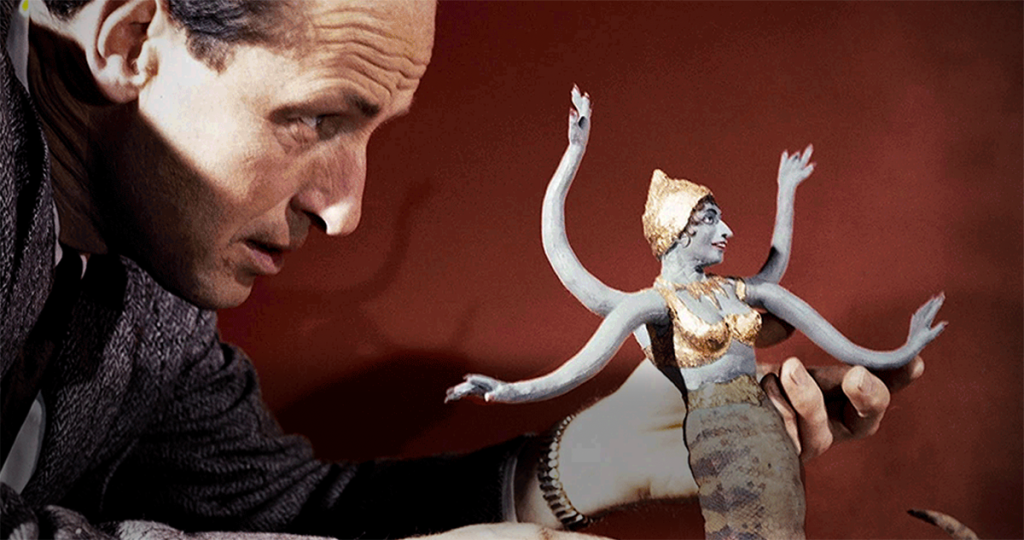

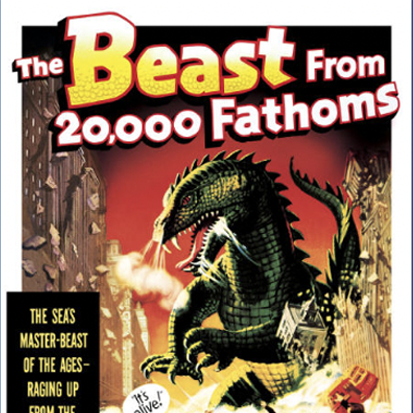

I believe that name was first attached to The 7th Voyage of Sinbad [1958], but you had been developing the process for several years, right?

Oh, yes, before that. Since The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms [1953].

So it would have been the same process on 20 Million Miles to Earth.

Oh, yes.

Which is being re-released on DVD.

In color! Because, you know, we would have shot it in color but our budget wouldn’t take it. At the time, color was very expensive so we had to shoot it in black & white.

What do you think of the colorization process?

Oh, I think Legend Films have done a wonderful job. We colorized She—Merian Cooper’s old film. He wanted to shoot it in color, but RKO cut his budget at the last minute and he had to shoot it in black & white. The picture wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea—it dealt with reincarnation. But we colorized She and it looks like it was shot in color.

I’m glad that 20 Million Miles is being released in color. It makes it a new picture. The color really helps things. You know, I worked really closely with Rosemary Horvath in colorizing it. She knew how to push what buttons to get the right shades. I’m not that up on computers.

Can you tell me about the process?

Well, it’s all done on the computer. I don’t know the details. I would just say, “I think this should look more bluish, because it’s ice, and this should look that way,” and we worked it out together.

It’s amazing how far the colorization process has come because I remember when King Kong was first colorized, it looked like a child had taken to it with crayons.

I know! Well, this is much better, believe me.

What do you think about using modern computer technology to enhance a film that’s more than 50 years old?

I think it’s good. It makes it sharper and you can do things digitally that are quite remarkable.

Is there anything you would have done differently had you been able to shoot the film in color?

No, not really. Black & white was so much easier to work with at the time, though. This process of rear-projection—there was a big problem in that when you photographed a projected image, the colors would change due to the lamp of the projector. That was a big problem on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad when we made it. But we overcame it by various processes.

You’re known for working alone.

Yes, I did everything myself—because there were no books at the time about special effects. Today there are a number of them. And everything is exposed about how things are done before the picture comes out. I think that spoils it. I used to keep it quiet because I know I was haunted for years about how King Kong was made, and I thought it was wise not to divulge everything.

So you worked alone to keep your work secret?

Not only that reason. I preferred to work alone because it requires a great deal of concentration. And I didn’t want to be talked out of anything.

I think it would surprise a lot of people to find that you, as a sort of lone-wolf animator, had so much creative control over the stories of your films.

Yes, I worked on the stories. I don’t just wear the animation hat. So, many times, I would bring the original idea in. 7th Voyage was brought in by myself, although I was very modest in those days and I didn’t realize that modesty was a dirty word in Hollywood—it took me 50 years to realize that.

And 20 Million Miles to Earth—that was your idea, too, correct?

That was originally my story, and then I got Charlotte Knight involved so I gave her the full credit. But it was originally my idea. I had it set in America, crashing in Chicago, in Lake Michigan, but I wanted a trip to Rome so I changed the location before I submitted the story to Columbia and Charles.

What did you think when you saw special effects houses like Industrial Light and Magic start to pop up?

It’s amazing that they made an industrial process of it because I found it very hard to rely on other people to do things. I’m amazed that they did it, and they did a wonderful job.

When you saw ILM’s work with Star Wars and so forth, did you feel threatened in any way?

No, not at all. I think there’s room for every technique, depending on the story. Stop-motion gives a quality to a fantasy film—I think if you make fantasy too real—that was half the charm of Kong: You knew it wasn’t real and yet it looked real. I get a lot of fan mail saying that they prefer my things to that of the computer-effects guys, who try to make it so realistic that it loses the quality of fantasy.

So, what did you think of the remakes of Mighty Joe Young—your own film—and King Kong, the film that inspired you?

Well, it’s another person’s point of view. Merian Cooper was a single producer, and they had five producers on the remake of Mighty Joe Young. They tried to do the concept realistically and it was a fantasy, you know?

What did you think of the special effects in the new King Kong, though?

They were brilliant. But you know, people don’t go see a film just because of the special effects.

I think they stretched it out, the new one. The beauty of the original Kong was that it was so compact. Right from the first word of dialogue, when he said, “Is this the motion-picture ship?” you knew what you were in for. The story was so compact—there wasn’t a superfluous scene in it.

Whereas the new one takes a bit of heat for being overly long.

Well, yes, because they go too far into Ann Darrow’s past. And people who go to see a picture like King Kong aren’t really interested in that. I think it breaks it when the girl tries to amuse the gorilla by doing tricks. It gets into the realm of Dino De Laurentiis’ remake.

Oh, come now. It’s not that bad, is it?

No, it was a wonderful film, but it’s a different point of view. Everybody has a different point of view, you know. And Merian Cooper, being an adventurer himself, he specialized in these adventure films.

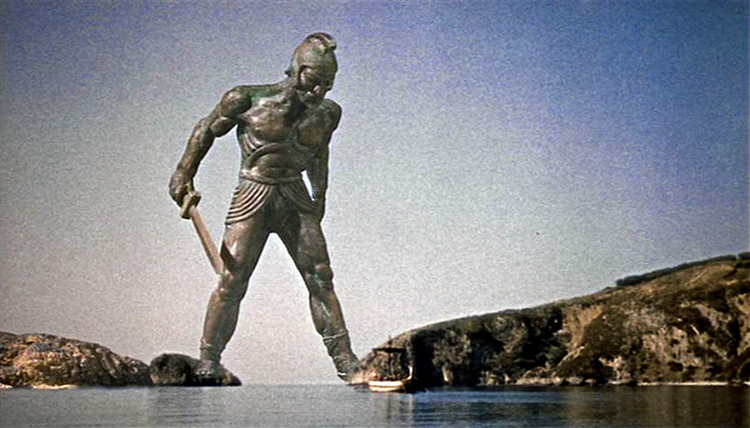

For someone my age, the film of yours that had the most impact was Clash of the Titans. That’s one of the major films of my childhood. But it was your last film. Why?

I don’t know. I just felt I’d had enough in the darkroom. After all, I did 16 features and did nine-tenths of the animation by myself. And most of it is the first take. We seldom had time to do retakes so unless there was something radically wrong, we would never do a retake. With computers you can go over and over and refine it and refine it without it showing, but when you’re dealing with film, the minute you try to dupe it, it gets dupey looking. So we had great limitations.

When you were making Clash of the Titans, did you have any idea it would be your last film?

No, not really. I just felt we’d had enough.

What do you think about the upcoming Clash of the Titans remake?

Well, I think it’s a mistake. They’re not going ahead with it, are they?

I can’t believe I’m the one saddled with the burden of telling you this but, yeah, unfortunately.

Good heavens. Well, I read somewhere that they wanted to make it realistic. That’s the worst thing you can do to a fantasy film! You know, Greek mythology is not supposed to be realistic. I think that’s their first big mistake. But life will go on, I suppose. You have no control over that.

On a happier topic, what are some of your recent favorite films? Have you seen many new films?

No, I’m not attuned to the latest concepts. They forget that there’s supposed to be a story told and they depend on cut after cut and dynamic zooms and eight-frame cuts, and that’s not my cup of tea. So I don’t see many recent films. The subject matter isn’t my cup of tea, either. They’re usually very depressing. I don’t like to sit for an hour and a half watching someone in the process of dying.

Given that so many people dislike CGI, why do you think filmmakers continue to use it?

Everybody wants to do things a little differently than the previous one. If someone makes a successful film, which has been going on for years, everyone jumps on the bandwagon and makes a similar type. And most of them depend on explosions.

What about things like Wallace & Gromit?

They’re wonderful, the puppet films.

But you never wanted to make them, right?

Well, I did. I worked with George Pal for two years in the early days and we made puppet films. His films were very stylized. But Wallace & Gromit, you know, it’s a field in itself. It’s not the type of thing we were making.

Both the new Wallace & Gromit film and Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride contained homages to you. They seem to be carrying the flame of your work.

They’re doing a marvelous job. Wallace & Gromit have been a big success and I get a big kick out of Creature Comforts. They’re very clever.

Mr. Harryhausen, it’s been a real honor to speak with you. Thank you so much.

Well, I’m delighted. Thank you.