Review: Raiders of the Lost Ark

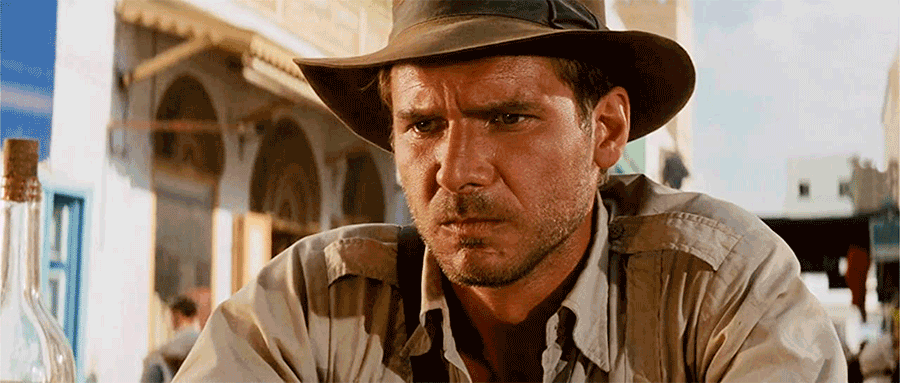

review | Raiders of the Lost Ark

The film that kicked off the Indiana Jones franchise receives a first-rate 4K HDR/Atmos makeover

by John Sciacca

update May 3, 2023

Wanna feel old? How about if I tell you that Raiders of the Lost Ark is celebrating its 40th Anniversary?! Wanna feel a little better about it? To celebrate this milestone, Paramount has re-released all four films in the Indy franchise, all restored and remastered in 4K HDR with new Dolby Atmos audio mixes with all picture work approved by series director, Steven Spielberg.

Besides remembering seeing the film in the theater when I was 11, I recall when Raiders was first released to home video. At the time, most titles were priced as “Rental,” meaning they were all like $80 and up and sold to chains like Blockbuster. Paramount decided to make a splash with Raiders in the home market, pricing it at a shockingly low (for the time) $39.95, and I remember rushing down to the video store and picking up a copy on Beta the day it was released, barely able to wait until I could get home and watch the finale in slow motion. The film went on to sell over a million copies by 1985, making it the bestselling film of its time.

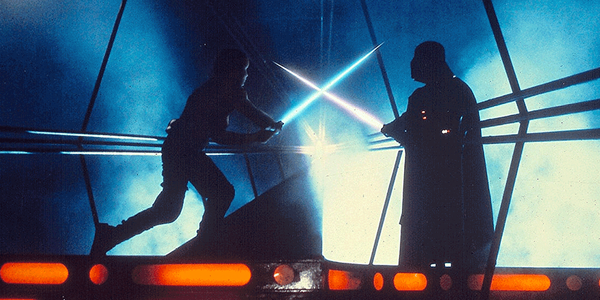

While the action/adventure genre is well established now, Raiders seemed shockingly fresh when it came out. For almost the entirety of its near-two-hour run time, you are pummeled with one action piece after another as Indiana is constantly thrown into increasingly impossible predicaments.

Sure, after 40 years, some of the bits—like Indy looking for Marion (Karen Allen) through the streets of Cairo as she is hidden in a basket—seem a bit cheesy and silly. But, I think the humor and B-movie-esque qualities are part of what makes it so much fun—such as when the Nazi Toht (Ronald Lacey) menacingly assembles what we think is going to be a weapon to interrogate Marion but what turns out to be a hanger for his coat, or when Indy just pulls out his gun to shoot the large sword-wielding thug, or Indy saying, “I don’t know, I’m making this up as I go.”

Originally shot on film, this transfer is taken from a new 4K digital intermediate, and it looks mostly fantastic. Closeups can have a startling amount of sharpness and detail. The daylight market and street scenes in Cairo are bright and fantastic, showing the sharp pattern of the bricks and stones, and the textured detail of the walls, and the weave of the baskets. Some scenes look so good, they could be from a modern film, such as the opening shot of the group crowded around the drinking game at Marion’s bar, or the scene of the Nazis at the dig site, which has incredibly sharp focus across the width of characters that fill the screen. I did notice that some scenes have inconsistent or soft focus, especially in the beginning and at the very end of the film when Indy and Marion are walking down the steps. This probably more noticeable because so much of the film just looks so good. I also noticed things like single vine strands or a single, ultra-fine spider web that Indy pulls along with him.

I never found film grain to be objectionable but it is definitely there and most noticeably in outdoor shots that show the powdery blue sky. We have enough grain for the film to show its film roots and retain tons of detail, without being softened away to look like digital mush.

While there was some effects cleanup, apparently this was mainly done to remove lines from the composites, and I never found it objectionable or noticeable in the way Lucas usually likes to go in and modernize his films. One change I did notice was that it was always apparent that the cobra striking at Indy and Marion was behind a piece of glass, and now that has been removed looking like they are in more peril. I also never noticed that the German phrase “Nicht stören” (Do not disturb) was written on one of the buildings in the map room. I’m sure it was always there but the new cleaned-up transfer and sharper resolution make it easier to notice small details like this.

Colors are natural throughout and the opening jungle scenes are both brighter and more contrasty than I recall them, with bright shafts of light pouring in through the trees and wispy smoke. Golds, especially of the Ark, look bright and brilliant. One scene with the lights in Marion’s bar and the various colored bottles of liquor backlit looked really good. Everything just looks as it should, whether it is the green jungle hues, the tans and browns of the desert, or the red-orange of fires. We also get really nice and deep blacks, and good shadow detail that really benefits from the HDR grading, making dark scenes look more natural.

The sound designers didn’t look to hit you over the head (pun intended) with the new Dolby TrueHD Atmos mix but just to heighten and expand the soundtrack. Right from the opening moments, you’ll notice the sounds of the jungle—bugs, birds, rustling leaves—filling the room and coming all around you. Inside the cave, you hear water drips and splashes that help put you in the scene, plus there’s the sounds of winds howling outside Marion’s bar, the cacophony of downtown Cairo, or the clinks and clanks of machinery aboard the German U-boat. Big obvious sonic moments like the giant boulder rolling overhead are enhanced with weight and texture and it now literally rolls over your head, or the thunder and lightning while they are about to dig into the map room, or the roar of the German plane’s propeller, and the spirits now fly and swirl all around the room and overhead at the big finale. We also get some decent subwoofer involvement when called for, such as explosions, vehicle collisions, or that big boulder.

John Williams’ iconic score is also given more room to expand in this mix, letting you appreciate his music more fully than even before. And all-important dialogue is kept clear and intelligible and mostly in the center channel, except for a couple of fun moments such as Marion screaming “Indy!” as she is being carried around the city in a basket.

Raiders is one of those classic films that belongs in every movie collection, and it has certainly never looked or sounded as good as it does here.

Probably the most experienced writer on custom installation in the industry, John Sciacca is co-owner of Custom Theater & Audio in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, & is known for his writing for such publications as Residential Systems and Sound & Vision. Follow him on Twitter at @SciaccaTweets and at johnsciacca.com.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC