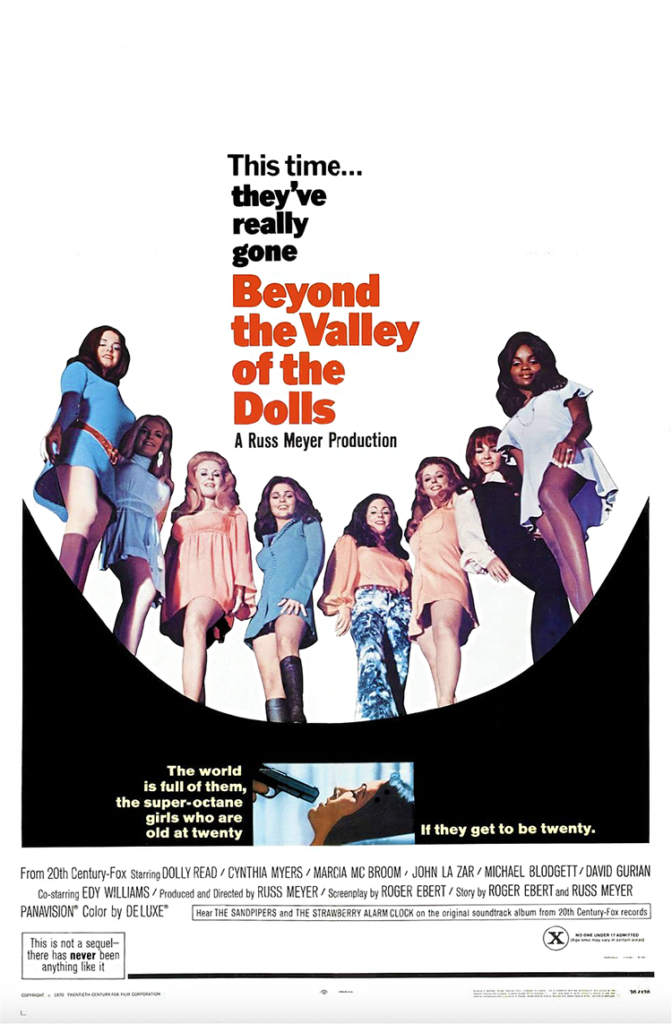

Review: Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

review | Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

Probably the most influential porn film ever, Russ Meyer’s evisceration of both the entertainment industry and the counterculture still packs a hell of a punch

by Michael Gaughn

January 13, 2023

This once-X-rated opening salvo in the effort to get soft porn out of sleazy “adult film” houses and into mainstream theaters is surprisingly well made, something of a masterpiece, and, by taking on a self-parodic tone no one had ever quite experienced before, yielded one of the most influential movies ever. It’s also spooked, channeling both the Manson murders and “The Teen Tycoon of Rock” Phil Spector, uncannily predicting Spector’s death-dealing future by 33 years, which can make watching it more than a little unnerving. Constantly poking and jabbing at the “no there there” of LA culture, coming at it from both above and below, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is the kind of film it never should have been possible to get made within the traditional studio system.

All movies are, in a sense, a product of their moment but few ever get to feed on that present as ravenously as Beyond, which devours it raw and with relish. It couldn’t have been made a year earlier, and would have just seemed tacky and sad done a year later. It had to spring from the cultural nadir of 1970, when all bets were off in a rudderless Hollywood desperate to seize on anything that worked. And realizing the once unthinkable idea of giving a pornographer the keys to the kingdom—not unlike Orson Welles given free rein of RKO to make Citizen Kane—lends this movie an infectious exuberance that somehow makes everything in it not just palatable but sublime.

Beyond is both very much of its time and an experience that hasn’t aged a day—partly because it’s so rampantly heedless and maniacally inspired and partly because it still serves as a wellhead for other movies, with no one yet able to top it. In a sense, like all great films, it just knows too much for anyone to completely exhaust it. If somebody had forced Douglas Sirk’s hand, it would have looked something like this; and it’s easy to trace a beeline straight from here to Alex Cox’s Repo Man. It’s like a boot camp for iconoclasts—and one of their last stands.

Simultaneously the lurid Victorian melodrama it says it is and its own parody, Beyond brought Nouvelle Vague-type self-reflexivity to American film, deploying it with a seemingly effortless dexterity. Its montage sequences—which are both integral to the story and standalone set-pieces of unparalleled goofiness but without ever succumbing to the temptation to pat themselves on the back—have never been bettered. (“In the Long Run” ranks with Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps as one of the genius moments of cinema.) It’s one of the first instances—you can also see it happening in Leone around the same time—of movies starting to feed on themselves, munching on their own tails. And, like the most satisfying art, it’s as deeply conservative as it is provocatively radical, deriving its energy from the collision, and symbiosis, of those fundamentally opposed moral and aesthetic spheres, transmuting that volatile act into something that miraculously hangs together—and that you feel compelled to watch exactly because of the sense it could all fly apart at any moment.

Beyond opens with the cheekiest credit sequence since Kiss Me Deadly, and, like Deadly, starts by knocking viewers off balance then does everything possible to keep them dizzy and disoriented for the duration. After a title card that basically tells the audience they’ve been lured into the movie under false pretenses, it then gives away the climactic scene, bringing a whole new meaning to “teaser.” But that big reveal, meaning little out of context, basically reveals nothing, and while it plays like something from a horror film, you ultimately find out it’s not more than a step or two removed from the Marx Brothers.

No one has ever equalled what Russ Meyer pulled off here, getting consistently strong portrayals out of a bunch of second- and third-stringers who ultimately wouldn’t fare any better than the characters they portray. John Lazar’s Z-Man is one of the iconic movie performances, a tightrope walk of virtuoso ham acting that somehow works but could never breathe for a second outside the confines of this film, which supplies all its oxygen. Yet Lazar, as great as he is in Beyond, would spend the rest of his career bouncing from one C-grade exploitation film to another. The top-billed Dolly Read made out even worse, scoring just a bare handful of minor one-off roles in series like Charlie’s Angels, Vegas, and Fantasy Island before disappearing forever beneath the waves. Meyer’s cast could hold its own against its counterpart in any A-list film, but its members all went exactly nowhere.

The 1080p streaming presentation on Apple TV is surprisingly true to the original film, with no obvious flaws when viewed on a big screen. There’s probably more that could be pulled out of the elements in a 4K release, but what’s here honors both the spirit of the film and of the time, and only the only fussiest could find serious fault with this incarnation.

The same can’t be said for the sound, unfortunately. While I suspect the problems are mostly or completely with the source tracks, some judicious cleanup could make some of the muddier moments more presentable and some basic balancing between scenes could help even things out. Be prepared to have to occasionally goose your levels once they’re set since some sections are so muffled and low they can sound like you’re hearing somebody having a conversation in the next room.

If you haven’t come across this film before and use criteria more meaningful than Oscars won or Rotten Tomato scores tallied to judge the worth of a movie, you’ll likely find an evening spent with Beyond the Valley of the Dolls a bit of revelation. While it’s no longer considered forbidden fruit and, having lost a lot of its original shock value, can seem even quaint to the jaded, there’s still more than enough here to offend contemporary sensibilities. Beyond is very much its own animal, both exhilarating and disturbing, with DNA so unique it’s been spared the indignity of being franchised. Very, very few movies approach the level of pure film. Beyond is one of them, and one of the best.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC