Review: Nightmare Alley

review | Nightmare Alley

Guillermo del Toro takes a cynical turn with this noirish thriller that evokes the ’40s without aping the film look of the time

by Dennis Burger

March 15, 2022

Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley is an unusual film in the canon of a director known for unusual films. A new adaptation of the 1946 novel by pulp editor William Lindsay Gresham that was also adapted for the screen in 1947 by Edmund Goulding, it has been promoted heavily as del Toro’s first to fall entirely outside the traditions of sci-fi or fantasy. But to this old fan of his work, that’s hardly as significant as many are making it out to be.

A far more interesting departure is the fact that del Toro has had to doff his anti-cynicism hat for this adaptation, and that—far more so than its rejection of the supernatural—is what makes Nightmare Alley feel so different. The director has certainly flirted with cynicism in the past, perhaps most notably with Pan’s Labyrinth, only to ultimately reject it. But to fully commit to this noir adaptation, he had to embrace it. And if there’s anything that keeps the film from knocking it completely out of the park, it’s that del Toro seems uncomfortable doing so.

It’s still a very good film, just not a great one—certainly not as great as his previous effort, The Shape of Water. But let’s not allow comparison to be the thief of joy here, because far more works about Nightmare Alley than doesn’t.

Its impact in large part hinges on star Bradley Cooper’s ability to play a man who seems to be in control—who believes himself to be the master of his own fate—but who ultimately isn’t. And in this respect, Cooper surprised me. He delivers a nuanced and layered performance that is, almost throughout, borderline hypnotic. The film is also bolstered by fantastic performances by Cate Blanchett, Toni Collette, and Rooney Mara, all of whom straddle a fine line between paying homage to the era in which the film is set and not feeling overly affected.

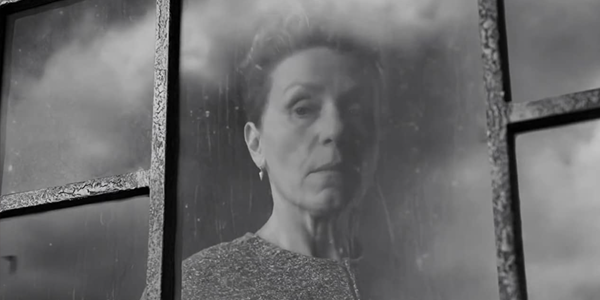

More so than anything else, though, Nightmare Alley is a work of cinema built on mood and tone, much of which is conveyed by its look and sound. One might have expected del Toro to ape or at least hint at the aesthetic of films of the 1940s, but instead he chose to capture the imagery in ArriRaw at 4.5K and 6.5K, relying on a mix of Arri Alexa and Arri Signature Prime lenses, with the film finished in a 4K digital intermediate.

No attempt has been made to film-look the footage, and as such it is shockingly pristine. Rather than manipulating the medium to add character to the imagery, del Toro and cinematographer Dan Laustsen seem content to let the textures of the sets, locations, and costumes—some slick, some gritty—do the talking.

The picture is also a study in contrasts, with a heavy reliance on low-key lighting and shadows that feel almost impossibly black. Every frame is beautifully composed, and nearly every scene relies on a careful balance of focus and lighting to draw the eye around the screen.

Comparing Kaleidescape’s UHD/HDR download to the HD version currently streaming on HBO Max and Hulu, there’s simply no contest. This is a picture that benefits from the enhanced resolution of UHD in its delivery of fine textures and details. But more importantly, it simply doesn’t work without the benefit of HDR. The enhanced dynamic range not only gives more breathing room to the stark contrasts but also gives the picture a deeply dimensional, 3D-without-the-glasses look of a sort I haven’t seen since Netflix’ Our Planet. It also makes the struggle between darkness and light that much more impactful, especially in the offices of Blanchett’s character Lilith, where the unique intensity of (seemingly) natural light filtered through window sheers defines the space as much as does its Art Deco architecture and furnishings.

And believe me when I say I’m as shocked to write this as you are to read it but the Dolby Atmos mix delivered by Kaleidescape adds something truly meaningful to the experience of the film, primarily in two ways. Firstly, it has be to noted that weather is an uncredited character in Nightmare Alley. In the first act, which largely unfolds at a carnival outside an unnamed small town, it’s always either storming or threatening to storm, and it’s the latter condition in which the Atmos mix really flexes. The thunder rolling on the horizon feels and sounds distant, not like a sound effect being generated from within the room. I think auditory illusions of this sort did as much to draw me into the off-kilter reality of the film as did the imagery.

As the plot moves to Buffalo, wind and snow take over as the dominant meteorological force, and the sonic impact is just as impressive. But there’s also this really neat aural effect—almost subliminal—in which the height channels are employed judiciously to bring, for example, the hum of mercury-vapor lamps overhead, which goes a long way toward selling the illusion of space and the sonic contrast between exteriors and interiors without becoming a distraction. Combine that with some stunningly effective panning across the front channels and punctuated, deliberate use of surrounds to keep the viewer unsettled, and there’s simply no denying that the sound mix is a work of art in itself.

That may not be enough to keep all viewers engaged, sad to say. Nightmare Alley is an incredibly deliberate long con that demands your constant attention but doesn’t often nudge you or hold your hand. You’ll hear no complaints from me on that front, as I love a slow burn, but this one burns so slowly you can barely see the flame moving.

I also love the fact that in addition to finding the beauty in ugliness—something that del Toro has long excelled at—in this film he cranks up the knob on spotlighting the ugliness lying just below the surface of superficial beauty. I just wish he had committed to his themes a bit more fully and consistently. Some are oversold and some are glossed over, and that does rob the work of some of its emotional momentum. Still, it’s a film that deserves to be appreciated, and it absolutely must be viewed in UHD/HDR. And with Dolby Atmos, if your surround system supports it.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

PICTURE | There’s no comparison between the streamed HD versions and Kaleidescape’s UHD/HDR download of this film. The enhanced dynamic range not only gives more breathing room to the images’ stark contrasts but also gives them a deeply dimensional, 3D-without-the-glasses look.

SOUND | The Atmos mix is a work of art in itself, adding something truly meaningful to the experience via stunningly effective panning across the front channels and punctuated, deliberate use of surrounds to keep the viewer unsettled

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC