Review: The Matrix Trilogy

review | The Matrix Trilogy

The imminent arrival of the first Matrix film in 18 years makes this the perfect time to revisit the original trilogy

by John Sciacca

December 17, 2021

You might ask yourself why we’re reviewing The Matrix Trilogy a full three years after its 4K HDR disc release. The answer is simple—with the new The Matrix: Resurrections dropping next week both theatrically and on HBO Max, it seemed the perfect time to revisit this sci-fi classic.

To be even more honest, it had been years since I’d watched this trilogy and I’d never sampled the 4K HDR release with the new Dolby Atmos audio soundtrack. I couldn’t even remember exactly how the story finished, so I decided to take the Red Pill and once again head down the rabbit hole with Neo, discover how these films hold up some 20 years later, and get ready for the exciting fourth chapter!

Released in 1999, it’s no understatement to say The Matrix was groundbreaking. Everything from the ad campaign (“Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself.”), to the look and style, to the visual effects was intriguing and mind-blowing. I can remember turning to my wife in the theater just minutes into the movie and saying, “I’m not even sure what is happening but I am loving this movie!” I’m happy to say that feeling holds up and the films are still a blast to watch!

And while the innovative “bullet-time” effects have been widely copied since, and even showed up in commercials for a while, the effects are still amazing to watch and, bolstered by the new Dolby TrueHD Atmos mix, are more immersive and impactful than ever.

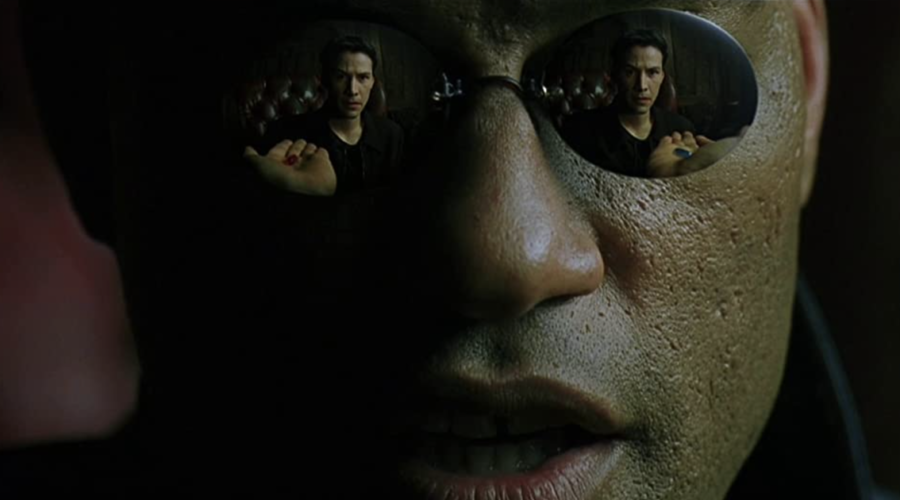

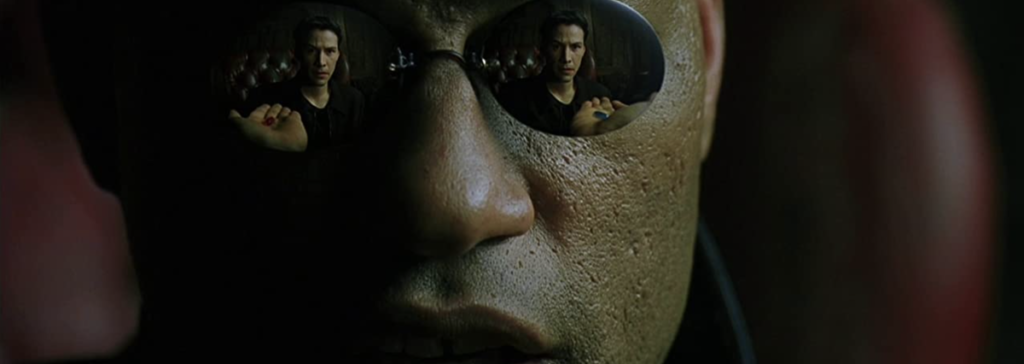

Ultimately, though, what makes The Matrix work and hold up so well it is that it is just so damn cool. The world is cool, the concept is cool, the style is cool. But most of all, the characters are cool. With lesser actors, some of the lines could have been laughable, but this cast committed to the Wachowskis’ vision, and they inhabit their roles and the world so well it’s easy to go along for the journey. Laurence Fishburne as the all-wise and believing prophet Morpheus walking around with arms folded behind his back in a leather duster and spouting things like, “My beliefs do not require them to [believe].” And Carrie-Anne Moss as Trinity, in her skintight, shiny black bodysuit, is never sexualized but rather an incredibly strong female lead every bit as vital to the story. Hugo Weaving as trilogy Big Bad Agent Smith brings gravitas to a character that is really just a computer security program.

And then there’s Keanu Reeves as Neo. Of course, now, after three successful John Wick films, it’s easy to separate Reeves from his “whoa, dude!” past performances but in 1999 he wouldn’t have been an obvious choice for this role. Of course, it’s impossible today to think of Neo as anyone other than Reeves, and he plays the part with the perfect amount of curious/confused, “What the hell?!” that we as the audience are experiencing; and the underlying excitement of lines like, “I know kung-fu” after an entire day of having fighting skills uploaded into his brain come across as wide-eyed discovered excitement rather than silly.

The first film, The Matrix, is still the best. It was a wholly original experience, and while the second and third films fleshed out the world—and completed the experience—the first one stands head and shoulders above the others. Though I actually enjoyed the third film, The Matrix Revolutions, this time more than I did on first viewing. (There is definitely something to be said for being able to view an entire story back-to-back-to-back instead of needing to wait years between releases.)

The parts I remembered as being great from the second film, The Matrix Reloaded—namely the scenes with the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson) and the amazing freeway chase rescuing The Keymaker (Randall Duk Kim) from The Twins (Adrian and Neil Rayment)—are still fantastic, while the bizarre and way too long club-rave scene in Zion still goes on far too long and The Architect’s (Helmut Bakaitis) convoluted speech with “ergo,“ “concordantly,” and “assiduously” is still a bit of a headscratcher but a very cool concept presented in a cool Matrix-y manner.

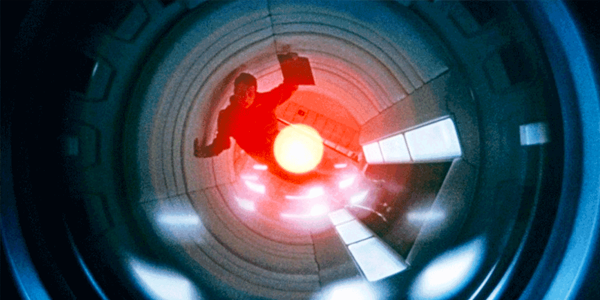

The films all have different feels while still feeling and looking like parts of the same whole. The Matrix is more a think-piece divided into three distinct acts of Neo discovering the Matrix, learning his role, and becoming The One, and introduces the concept of this other world and what is possible when you become unplugged and learn how to control it. Reloaded builds out the mythology of who Neo is and what he can do and introduces the new threat replicating and emerging in the computer world, with Zion under imminent attack by the machines. And Revolutions is an all-out action assault as most of the characters are defending Zion while Neo and Trinity go off to confront the machines in Machine World.

I also can’t recall a film prior to Reloaded that ended on such a drastic cliffhanger, literally just ending and setting up the opening for Revolutions. (Much the way The Hunger Games: Mockingjay—Part 1 concluded years later.)

All three movies were originally filmed on 35 mm stock, and these releases, taken from new, true 4K digital intermediates, look fantastic. The movies have the perfect balance between clarity, sharpness, and detail without scrubbing away noise into waxy softness. Only occasionally did I notice any grain/digital noise, usually in scenes with loads of all-white, like inside The Construct.

Edges are sharp and defined, and closeups have tons of detail. (I’d never noticed the pock marks on Reeves’ cheeks before—though certainly nothing to compare with Fishburne!). Whether it’s the texture aboard the interiors of the ships, or the construction of the human world of Zion, or the weaving of clothing in the “real world,” or the detail of the mechanized robots, or the stone and pebbled finish outside Neo’s office building, images are terrific-looking throughout.

You just get clean beautiful images that are the best these movies have ever looked, and the HDR grading makes this an entirely different visual experience. Blacks are deep, dark, and clean; colors are punchy, vibrant, and vivid; and bright highlights shine off the screen, especially in Resurrections during the final battle, which has plenty of eye-reactive lightning strikes. Right from the opening credits, the brilliant green text leaps off the screen, then there are plenty of highlights from lights aboard the ships or of autos, or brilliant orange-red flames or sparks of electricity.

Sonically, the new Dolby TrueHD Atmos track is another massive improvement and launches this series into the hallways of legendary demo material that showcases some of the best of dialogue clarity; massive, tactile bass; subtle atmospherics; and fully overwhelming immersive audio.

Take a listen to subtler moments, such as aboard the crashed ship in Revolutions. You’ll hear creaks and groans; venting gasses; crackling sparks; buzzes, clicks, and hums; and sounds of dripping fluids. There are other moments with deep rumbles of rolling thunder where you can pick up the individual droplets of rain falling. They are subtle but literally all around you, truly the hallmark of what an immersive audio track should deliver.

Of course, the movies’ huge action moments deliver the goods, and each film has its own truly demo-worthy scene, from the lobby shootout in The Matrix and the freeway chase in Reloaded to the attack on the dock in Revolutions. The gunfire is big and explosive, with reports and ricochets that wreak havoc and destruction all around the room. You’ll hear things collapsing and crumbling overhead, feel the ripples as bullets streak through the room, hear the race of cars blasting alongside you as Trinity races in her Ducati, and hear Sentinels crawling all around, behind, and overhead in a truly 360-degree surround field.

The Matrix Trilogy belongs in every collection, especially in 4K with the new Atmos audio mix. It is the epitome of exciting home theater viewing that is not only engaging but also highly entertaining. If you haven’t seen it recently, give it a rewatch so you’re caught up for Resurrections, the first new Matrix film in 18 years!

Probably the most experienced writer on custom installation in the industry, John Sciacca is co-owner of Custom Theater & Audio in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, & is known for his writing for such publications as Residential Systems and Sound & Vision. Follow him on Twitter at @SciaccaTweets and at johnsciacca.com.

PICTURE | The 4K HDR transfers have the perfect balance between clarity, sharpness, and detail without scrubbing away noise into waxy softness.

SOUND | The new Dolby TrueHD Atmos mixes launch this series into the annals of legendary demo material, showcasing the best of dialogue clarity; massive, tactile bass; subtle atmospherics; and overwhelming immersive audio.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC