hidden

treasure

getting the private cinema profiled in spanish treasure to sound its best meant digging deep into the tricks of the acoustic trade

BY DENNIS BURGER

November 30, 2022

“The eye doesn’t always tell you the flavor of the room,” says Anthony Grimani, former director of technology for THX and founder of Performance Media Industries, who was responsible for making this gorgeous private cinema sound the way it sounds.

This was in response to a pretty simple but open-ended question from me: “How?”

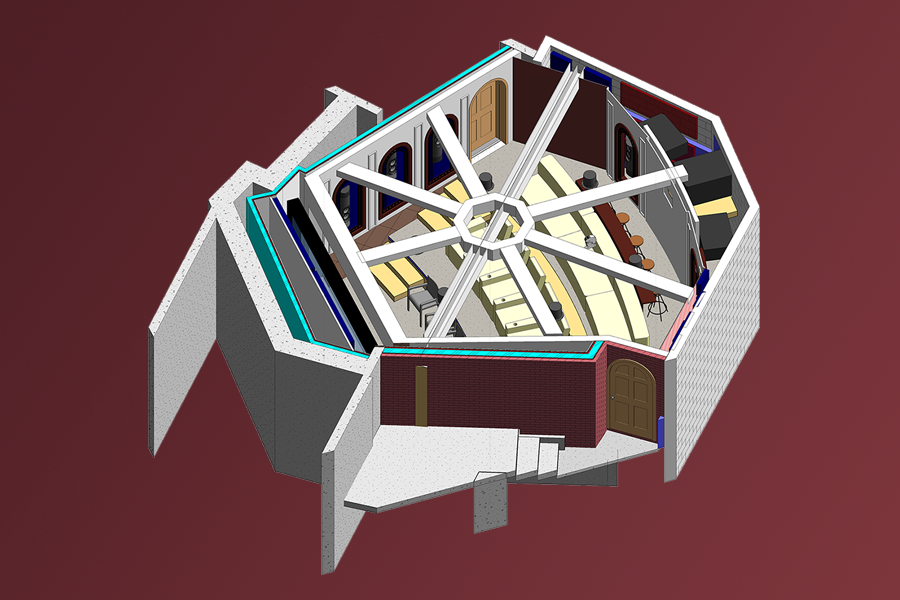

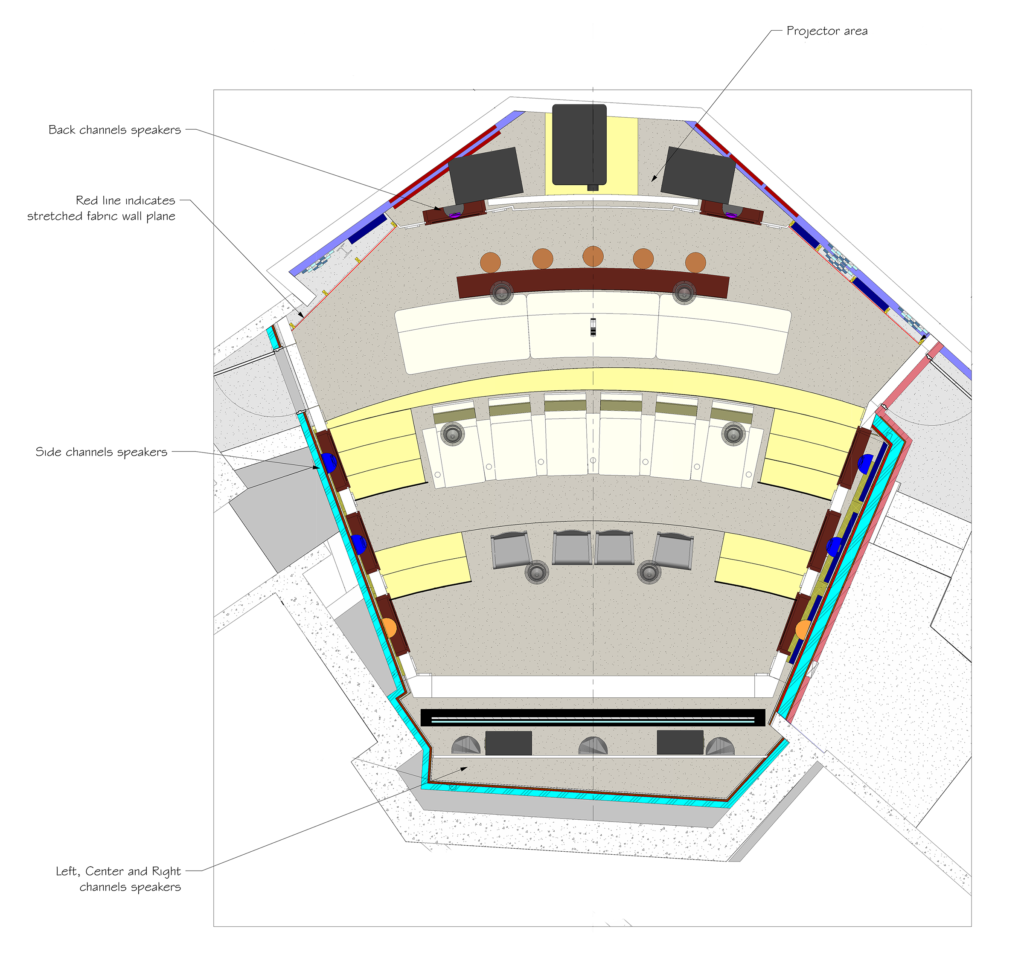

How, for example, does this space feature a complete Dolby Atmos sound system with six overhead speakers—not to mention 11 ear-level speakers and four powerful subwoofers—when a quick glance at the ceiling reveals not merely a complete lack of obvious speaker grilles but rows upon rows of hand-painted and antiqued wooden panels adorned with crests instead?

How does the tryptic back wall, with a shape not unlike the outfield wall of a baseball stadium, not reflect and concentrate sound back toward the seating area like a satellite dish? How, for that matter, do all the plaster and brick walls not create the sort of echoey and reverberant sound you’d typically hear in a room with so many hard surfaces? Look around and you’ll see none of the heavily draperied walls or acoustical treatments typically found all over private cinema spaces.

project team

acoustical designer

Anthony Grimani

Performance Media Industries

custom integrator

Bradford Wells

Bradford Wells & Associates

architect

Wylie Carter Architects

theater designer

Lisa Slayman

Slayman Cinema

contractor

“The surfaces in this room are not what they appear to be,” Grimani says. Starting from the top, he tells me that a number of the wooden crests in the ceiling were “knocked out, photographed, printed with dye sublimation onto an acoustically transparent fabric, then repositioned. Some of those panels hid speakers. Some of them hid acoustical treatments. So, half the ceiling is wood and the other half is fake, but you can’t tell. You walk in the room and the printing is so well-executed that it just looks real. To the naked eye, there’s just no way to know.”

In a sense, all of this makes this room a truly apt metaphor for cinema at its best. Like movies themselves, this private screening room relies on visual trickery and a lot of technical wizardry—special effects, if you will. And as with cinema, the best visual effects are the ones you don’t even realize are visual effects. They’re the ones you take for granted.

Take the matter of acoustical treatments around the room as another example. Any good screening room needs the right balance of two types of treatment, referred to as “absorption” and “diffusion.” In practice, it’s a lot more complicated than that, but if you understand those two concepts, you’re at least conversant in the fundamentals of what makes some rooms sound good and others sound less good, at least for the purposes of watching films.

Without enough absorption, a room will sound like a basketball court, more so the more reflective surfaces it has. Too much absorption, though, and it starts to sound dead and lifeless—perhaps even a bit unnerving.

And not only is finding the right amount of absorption important; you also need to distribute your absorptive sound treatments evenly around the room. Absorb too much sound in the front or rear, Grimani says, and “your ear/brain senses that as a black hole of sound energy; your attention is drawn to it. It doesn’t match our auditory radar. So it’s better to have a layout where the absorption is consistently distributed all the way around the room.”

You also want to create some diffusion—or scattering—of the sound that would otherwise reflect directly off the hard surfaces of the room. The placement of these diffusive treatments is equally important. “Some diffusion on the lateral surfaces on the side walls is good,” Grimani says, “since it gives you a sensation that the room is bigger than it really is.” Too much diffusion in the wrong places, though, and it “confuses the hell out of your senses.”

As for the physical makeup of these treatments, there’s a range of materials used to create absorption and diffusion—but nowhere on that list will you find plaster or brick. So where did they hide the treatments in this room? Behind the plaster. Behind the brick. And no, that didn’t involve dye-sub printing fabric panels to look like plaster and brick.

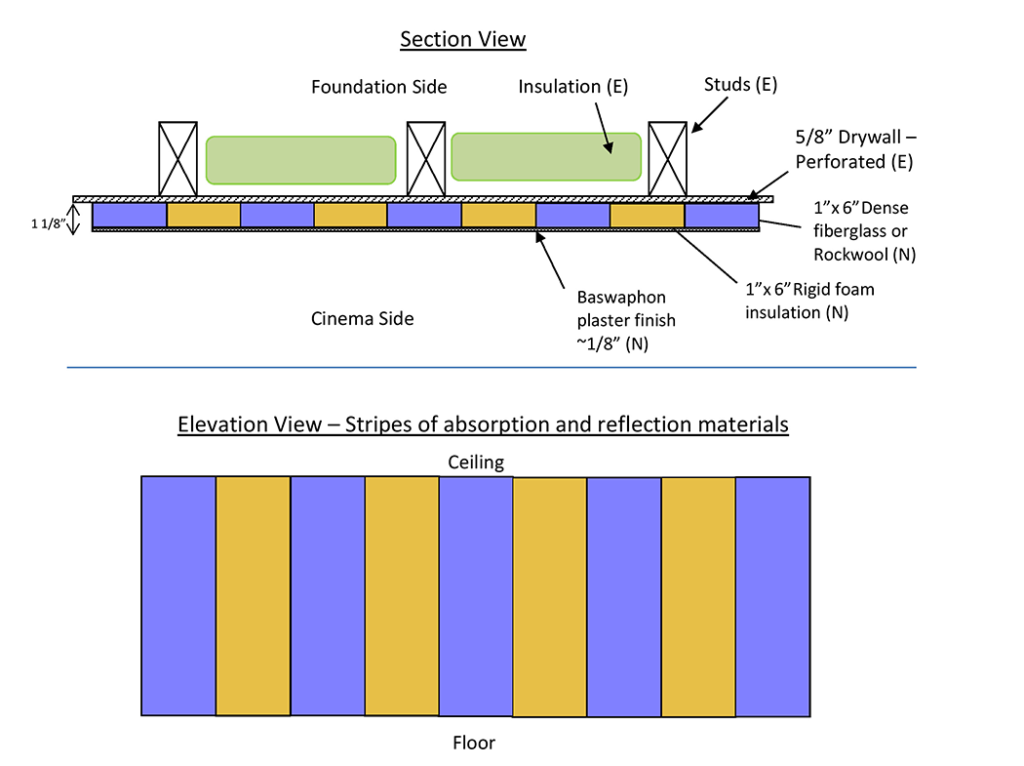

“The magic we used here was something called Baswa Phon acoustical plaster,” Grimani says. “The idea is that you lay up a few inches of relatively dense fiberglass or rockwool, then you trowel on this porous plaster, which lets the sound through. So while your eyes see plaster, the sound waves pass right through it and get soaked up by the fibrous material. So that’s part of the trickery.”

The brick walls along the sides and rear also hide secrets—in the back of the room specifically, two large subwoofers positioned and calibrated to complement another two subs behind the screen at the front. “You can’t tell from the pictures but the grout between the bricks was selected for its porousness,” Grimani says. “We also have fiberglass put right behind the grout. The area between the bricks is actually absorptive, so while this all looks like hard surfaces that would be a giant amplifying echo box—a parabola focusing all these reflections back at you—the room actually has a very natural acoustic character.”

The other key to making this room sound the way it does was reliance on Grimani Systems’ own powered speakers, which he convinced integrator Bradford Wells to use after a private audition. (In fact, it was Wells who brought Grimani into this project and handled all of the client interaction.) The speakers were engineered with spaces like this in mind. Due to their design, Grimani has precise control over how each driver in each speaker interacts with the other, which gives him more control over how each speaker delivers sound into the room. The goal is to make sure that whether you’re listening to the speaker from directly in front of it or off to the side, it doesn’t sound radically different.

This means that any sound that does bounce off the walls, ceiling, and floor has the same character as the sound reaching your ears directly. “What’s more important than focusing on the Grimani Systems label on these speakers,” he tells me, “is to state the importance of having a speaker with even sound power. That will help ensure good sonic results”

The state-of-the-art speaker system, the room tuning, the hidden acoustics, the climate control vents engineered to keep air velocity low to minimize the noise therefrom—all of it adds up to just one piece of the puzzle that makes this room work. Probably the most important piece is the collaborative effort of all the trades involved in the project.

“All successful theaters have to exist as the perfect combination of beautiful architecture, gorgeous design, and meticulous engineering,” Grimani says, “so that the picture and sound are all reference quality—meaning that a film director and sound mixer could come in and say, ‘Yep! That’s the picture and sound as I created them.’ The room also has to be carefully built to follow the rules set forth by the engineering and design and architecture. The team has to work together as a group to make that happen. Pull all that off and you end up with a crazy-happy client.”

So was the client crazy-happy? I couldn’t help but ask.

“It’s funny,” Grimani replies. “He said he originally thought he’d use the room once or twice a month but he’s down there every night.”

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

related article

“All successful theaters have to exist as the perfect combination of beautiful architecture, gorgeous design, and meticulous engineering.”

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC