review | 2001: A Space Odyssey

recent reviews

click the image to enlarge

As close as you’ll get to having the full experience of Kubrick’s space-travel epic without building a Cinerama at home

by Michael Gaughn

November 11, 2020

1968 (as I mentioned in my review of Rosemary’s Baby) was the year Hollywood, no longer able to lure people into theaters, blew everything up and started all over again. 2001: A Space Odyssey was the most radical product of that very radical year—not only because it flouted all the conventions of mainstream storytelling but because it went full-court Brecht to subvert the audience’s addiction to identifying with the protagonist, refused to use dialogue to Mickey Mouse viewers through the action, openly pissed on the convention of the traditional Hollywood music score, and stubbornly refused to be wedged it into any identifiable genre.

2001 is utterly sui generis—no film had looked anything like it before then; no film has looked anything like it since. It exists in its own, somewhat rarefied, universe.

Kubrick would never do anything that overtly adventurous again. Sure, Clockwork Orange was more outrageous but kind of in the same way as Dr. Strangelove; and “outrageous” isn’t the same thing as “adventurous.”

But neither adventurousness nor outrageousness on their own, or even together, are enough to make a film great. (The path from 1968 to the present is littered with the corpses of films that managed to do both, but little else.) 2001 is great because it sets an impossibly high bar and almost achieves it. Adventurousness and outrageousness are symptomatic of that ambition, but neither is essential to realizing it.

Which is why—to again return to an earlier review—I have to give The Shining the edge as Kubrick’s most accomplished work. Almost everything he does big and bold in 2001 he achieves quietly and more deftly in that later film. 2001 is the product of an artist so giddy he can’t help showing off; The Shining is the work of a master so confident in his abilities that he can just quietly drop clues and then wait as the rest of us scurry to catch up.

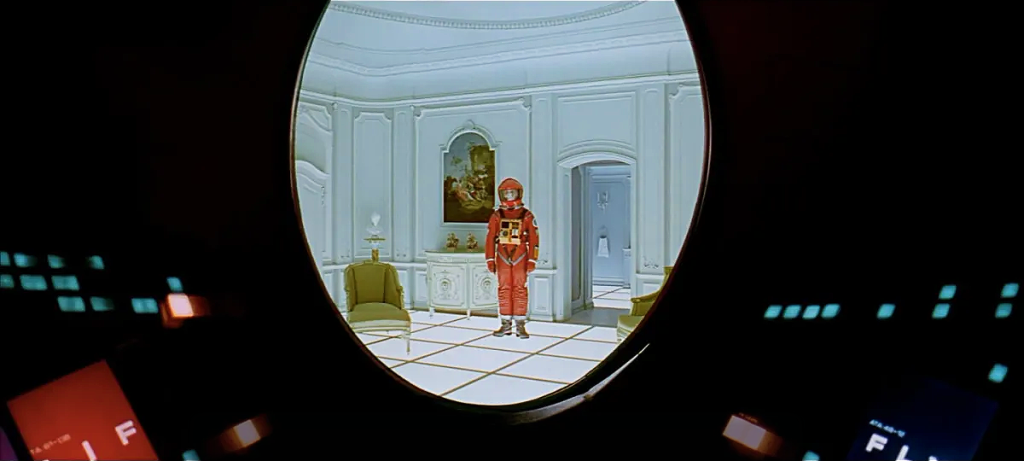

But why even go into all this? Because both 2001 and The Shining hinge on the experience of pulling you deep inside the film—not in a superficial, escapist way but so you begin to have the sensation of actually occupying the same physical space as the characters.

That the 4K HDR presentations of both films are reference-quality seriously ups the “you are there” ante—but with a crucial difference. And there’s the rub. The Shining is almost one-to-one true to the movie Kubrick created. When you watch it at home on a high-quality system, you’re seeing what he wanted you to see. 2001 in 4K HDR is just as extraordinary—but as a title card in the closing credits reminds you, this was originally a Cinerama presentation. And, unlike most of the other filmmakers who dabbled in Cinerama, Kubrick didn’t deploy it as a gimmick (Grand Prix, anyone?) but made it absolutely central to creating that sensation of taking an epic voyage into space.

So, is 2001, viewed in 4K HDR, in any meaningful way inferior to The Shining? On the technical level of the transfer, no, they’re both excellent—almost flawless. But since you can’t do Cinerama at home (at least not without a hell of a jerry-rigged setup that would have to verge on ludicrous), The Shining is truer to the original film.

All of the above is really just an exercise in praise by faint damning. The Kaleidescape download of 2001 is one of a handful of films so well served by the 4K HDR treatment that it has to be part of the foundation of any serious film collection. If there’s a single significant hiccup in this presentation, I didn’t see it.

To get lost in 2001 today, you have to get beyond ticking off what has and hasn’t come to pass and look past all that Swinging ‘60s clothing and furniture and get on the wavelength of the film Kubrick actually created, which exists in an elaborate and self-consistent world that merely uses the trappings of reality to achieve escape velocity.

The 4K resolution can’t reveal every detail of the original 70mm print, but it shows so much more than any previous home video incarnation that it’s shocking to realize to what extent Kubrick created outside his era, how unencumbered he was by the stylistic ticks of that time (or even of the future). On the level of film technique and film grammar, 2001 still holds.

What really takes the experience to a new, truer level is the HDR. Yes, many of the special effects now even more obviously look like still photos traveling across painted backgrounds. But shots of actual physical objects in motion, like the space station, the Discovery, and most of the extravehicular footage of the pod, are stunning. The brightness of objects in space is one of the things 2001 got basically right, and the HDR makes them look so crisp and cold they’re almost tactile.

Scenes to check out include the scientists walking down the ramp into the lunar excavation, where Kubrick shoots directly into a large worklight, with the light so intense you almost have to look away. The beginning of the final act, where the floating monolith guides Bowman into the Stargate, is especially compelling because of the convincing luminosity of Jupiter and its moons. And the virtual hotel room where Bowman goes through his transformation, which Kubrick created to mimic the look of early video, is more convincing with the white and other light tones pumped just enough to glow without becoming bloated or diffused.

As for the audio: Talking about the soundtrack of 2001 has always been kind of a ticklish business because this is essentially a silent movie. Kubrick rediscovered and then reinvented the core grammar of silent film, much of which had been glossed over and obliterated by the tyranny of the microphone during the Studio Era, and used it to not just drive this film but all of his subsequent efforts. It’s not that the audio is superfluous; it’s just not redundant with the visuals the way it had been since the introduction of sound—and continues to be.

(Curiously, another product of 1968—Blake Edwards’ The Party, which was much maligned at the time and is now revered—is also basically a silent film. Edwards, on a parallel track with Kubrick, dipped back into silent comedy to bring a sense of grace and redemption that had been missing from movie comedies since the Chaplin era.)

So, things like The Blue Danube, the heavy breathing, and the various warning sounds all sound perfectly fine. But this is a film of stripped-down and barren environments, without warfare or roaring engines, so there’s, thankfully, little audio-demo fodder to be found.

As for the extras—all I can say is “beware.” I’ve already sufficiently dumped on the team that created (although that seems far too kind a word) the promotional videos disguised as mini-docs included with Full Metal Jacket and The Shining. Their efforts here are equally awful. The other videos here are just as irritating and, for the most part, pointless. It would be great if somebody could unearth the Primer to “2001” Keir Dullea hosted on CBS in the late ‘60s. It would make all these other efforts seem superfluous.

The trailer included here isn’t the one from its initial release or even its legendary initial re-release but a contemporary stab that feels like a cliché film-school exercise (people are going to look back 20 years from now at our addiction to dips to black and laugh their asses off) and indulges in exactly the kind of manipulative melodrama Kubrick despised.

The only extra worth going out of your way for is the extended audio-only interview Jeremy Bernstein did with Kubrick in 1966. You get to hear the director walk through his whole career to that point, beginning as a failed high school student who became the youngest photographer ever at Look magazine and then went on to learn filmmaking, in a world without film schools, by making his own features. Not only is it better than anything any writer has ever done on Kubrick, it confirms, beyond a doubt, that Peter Sellers’ Quilty in Lolita is basically an extended Kubrick impression—which puts that deeply flawed film in a whole new light.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | The Kaleidescape download of 2001 is one of a handful of films so well served by the 4K HDR treatment that it has to be part of the foundation of any serious film collection.

SOUND | Things like The Blue Danube, the heavy breathing & the various warning sounds all sound perfectly fine, but this is a film of stripped-down and barren environments, without warfare or roaring engines, so there’s little audio-demo fodder to be found.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC