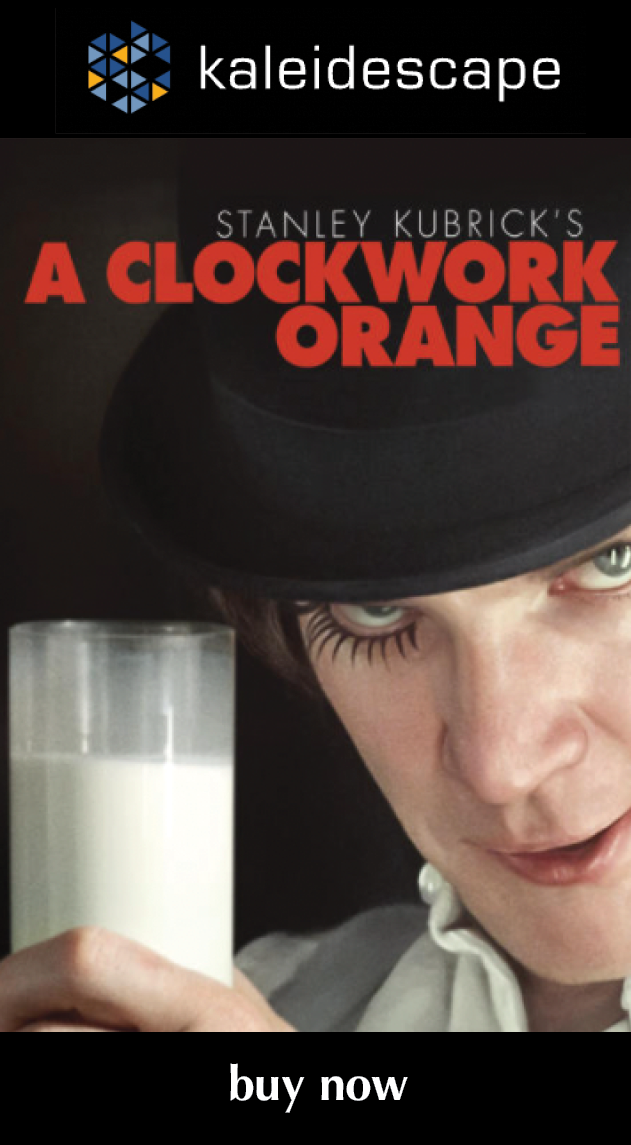

review | A Clockwork Orange

The stunning quality of this 4K transfer redeems Kubrick’s most notorious film, rekindling its initial excitement

by Michael Gaughn

October 1, 2021

It’s traditional to save comments about video quality until the two-thirds or three-quarter point of a review, but I have to cut right to the chase: This is a stunningly gorgeous transfer of a deliberately ugly film—the best I’ve seen Kubrick’s picaresque stroll through depravity look since I watched an archival print on a Moviola.

From its opening image on, Kubrick meant A Clockwork Orange to be the anti-2001. After doing a big-budget Cinerama epic full of elaborate sets and effects for MGM, he decided to go lean and mean with his first project for Warner Bros., opting for a minimal crew and existing locations, except for one simple small set. And he completely rethought his approach to cinematography, using Orange as a kind of laboratory to experiment with, and essentially reinvent, the whole aesthetic of commercial film.

Kubrick had been trying to recreate the look of practical lighting since his first efforts in the early ‘50s, and various directors—most notably Godard—had made great strides with that approach throughout the ’60s; but with Orange, Kubrick finally nailed it, coming up with a way of presenting and perceiving “natural” lighting that not only defined all of his films from then on but has been the go-to look of Hollywood filmmaking ever since—for better and, often, worse.

Clockwork Orange is deceptive—so much so that, even though I know it well, it misled me when I watched it in HD a few months ago on Netflix, where it looked like hell. All of that dimness and grime just made the subject matter that much more unpleasant, and I regretted I’d taken the time to check it out.

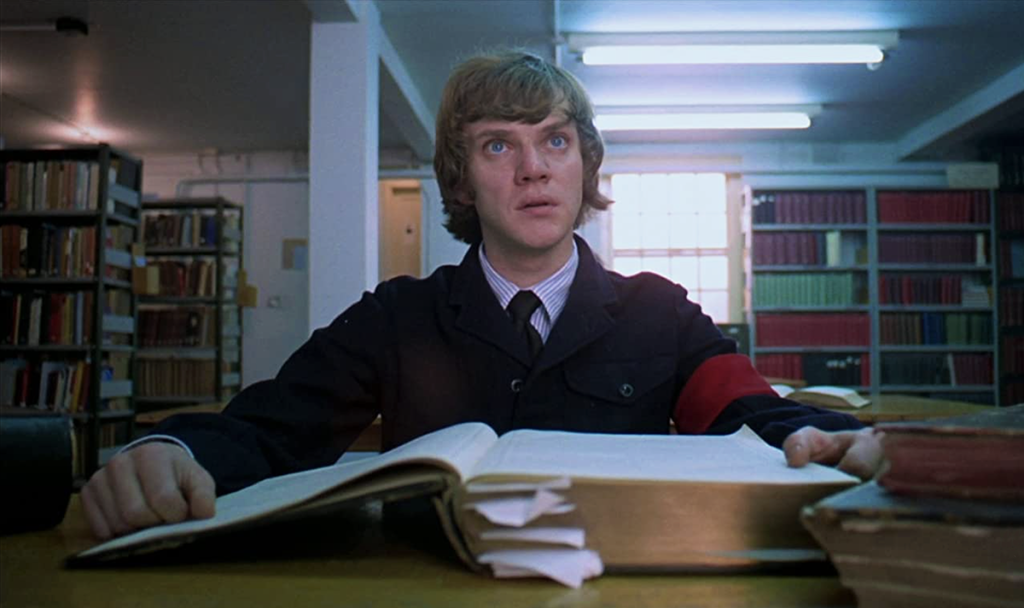

Seeing it in 4K HDR took me back to my early experiences with, and excitement for, the film. And that changed perception all hinged on seeing the cinematography done absolutely right. Kubrick was indisputably aiming for grunge—a goal he achieved in spades. But he did it with a subtle, and puckish, elegance and elan that makes the images not dispiriting but thrilling. Watch this film in anything other than 4K HDR and you’ll miss the twist the whole experience pivots on.

A couple of examples among an abundance: In earlier releases, the lettering could look painted onto the milk-bar walls; here, the letters stand out in distinct relief, enhancing the tactile sense of the environment. There are closeups and medium shots throughout that are literally breathtaking, but the closeup of Malcolm MacDowell as he dresses down his gang in the lobby of his sub-human apartment building is jawdropping in its clarity and immediacy. Yes, there are some soft frames here and there, but they most likely looked that way in the original footage.

See this movie as just about the subject matter and you can be in for a miserable time. Just as important is getting on the wavelength of the astonishing creative energy Kubrick poured into the project. You can actually both sense and see him throwing out the remaining rules of the studio system and discovering filmmaking anew, and clearly enjoying every second of it. Orange is not his best film but it’s probably his most inventive, and seeing that unbridled virtuosity on display can make it a heady ride.

Sure it’s dated as hell—any time you riff on the future, you’re going to date your film. But Kubrick showed he was aware of that by not really imagining a future, like he did in 2001, but by imagining an even more grotesque present—which is why Orange’s future has aged better than 2001’s. No point in presenting a lot of examples to back up my point—just look at the old women in the film walking around in purple wigs and then the old women in the present doing the same, and I’ll rest my case.

Probably the most ironic thing abut Clockwork Orange seen today is how wrong Kubrick got its crux, violence. For someone so deeply cynical, he assumed people in the future would still maintain some kind of essential repugnance toward violent acts. In other words, he saw some residual, positive value in a shared sense of decency. He couldn’t have been more blind to that vast act of social re-education and desensitization called the ‘80s, which replaced the deeper and more skeptical cynicism of the ‘60s with a far more facile “everything sucks” version that would just roll violence into the overarching oppressive apathy and see it deliberately deployed as yet another cultural wedge. This would all eventually mutate into the even more facile, and juvenile, current fascination with “dark.” Kubrick was often accused of presenting his characters as dehumanized—even he didn’t see how quickly we’d get to that point, let alone how enthusiastically we’d embrace it.

Orange can no longer shock—the pornographic, in all its forms, has since become commonplace, accepted, and encouraged—but it can still entertain. Malcolm MacDowell doesn’t have complete control over his performance but his sometimes reckless careening leads to some giddy highs. And Patrick Magee’s turn as the “writer of subversive literature” who becomes grotesquely unhinged from watching MacDowell’s rape of his wife is masterful—the kind of thing Sellers pulled off over and over in Strangelove but done here with a kind of dada collage feel that’s astonishing to watch.

And it’s a thrill just to savor Kubrick’s mise en scene—how he found unsettling ways to convey essential moments of the film without once stumbling into the arbitrary wackiness and poor-man’s surrealism that marred—and sank—so many late ‘60s/early ‘70s movies. In none of his films was he ever more of a punk than he is here, and it’s a cause for celebration because it shows how deeply expressive and subversive commercial film can be—and has rarely been since.

As for the extras—sorry, I’d prefer to refrain from any comment here but they’re by the same inept team of ne’er-do-wells that’s plagued the other Kubrick releases, and the best word for their efforts—if I may call them such—is inexcusable. Criminally so.

From Strangelove in 1964 to The Shining in 1980, Kubrick produced a sui generis string of genius films, all clearly cut from the same cloth but all, in very fundamental ways, radically different. And along the way, he completely changed how movies are conceptualized, made, and perceived. No one has ever equalled that accomplishment, and I think it’s safe to say no one ever will. The whole history of American film pivoted on Clockwork Orange. But forget all that—just cue it up in 4K and savor it as the dangerous act of pure film it very much is.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC