review | A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy

This would rank as one of Woody Allen’s best films—if he’d just spent some more time figuring out the ending

by Michael Gaughn

February 3, 2021

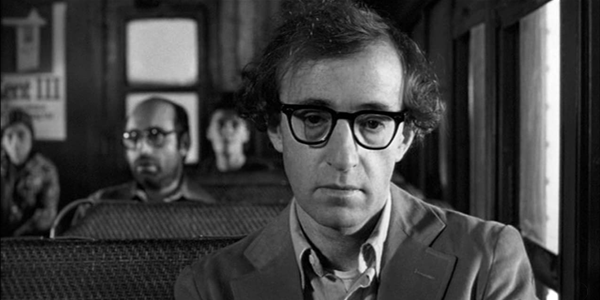

It’s got maybe the worst title ever and probably the worst ending of any Woody Allen film, but wedged between the opening-title card and that Third Act that got away is one of Allen’s best films, an almost perfectly balanced ensemble piece that’s probably the best evocation ever of midsummer, which is especially amazing when you consider how much Allen hates the country.

A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy was his first film with Mia Farrow and kicked off the diverse and more subdued but still fecund era that followed the tremendous creative explosion of Annie Hall, Manhattan, and Stardust Memories. Allen shot Sex Comedy simultaneously with Zelig, which he now admits wasn’t such a great idea but led to two amazing miniatures. He and Farrow would then do such standouts as Broadway Danny Rose (one of his best), The Purple Rose of Cairo, Hannah and Her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and the superb but troubling Husbands and Wives. After their all too public breakup, Allen would spend the following decades wandering in the woods, producing far more misses than hits, but occasionally conjuring up gems like Bullets Over Broadway, Mighty Aphrodite, and Blue Jasmine that, at the end of the day, still give him a higher overall batting average than any other first-rank filmmaker.

What makes Sex Comedy different from almost every other one of his films (and there are a lot of them) is that he apparently decided to start by capturing a certain time of year—the feel of the peak of summer—and then build a movie around it. He and Gordon Willis had already done something similar with Manhattan, where no other film has done a better job of evoking the sense of the Upper East Side at night. You’re not just watching the people stroll the streets—you’re right there with them, which creates an irreplaceable bond with the characters.

Here, you’re placed in the midst of the country that sits just on the cusp of the city—more specifically, Westchester County, just north of Manhattan—which is conveyed in such a way that it feels like both the city’s complement and dialectical other. This is some of Willis’s best cinematography, which is saying a lot, managing to capture that elusive sense of warm days, abundant nature, and lingering light. There is a reliance on day for night, which creates some unevenness toward the end, but is only really egregious in a shot of Tony Roberts leaving the front of the summer home to go off into the woods.

I was pleasantly surprised by how well Willis’s images came across in Kaleidescape’s Blu-ray-quality HD presentation. The subtle gradations are for the most part there and it’s possible to get lost in the frame while being only occasionally jarred by blown-out bright spots like the full moon. Of course, this film would likely look superb in 4K HDR, which would pull out the abundant detail in the fields, the interiors, and especially the period clothing, but I have no significant nits with the look of the film in its current incarnation. (And, given where this film stands in Allen’s body of work, and his current status in general, it’s not like Sex Comedy and 4K are likely to cross paths any time soon.)

Sex Comedy marks a big step forward in Allen’s evolution as a director, displaying a new maturity with his handling of the cast. Mary Steenburgen, Jose Ferrer, and Farrow all give nuanced, engaging performances that help reinforce the heady atmosphere of the film. Allen is even able to make Julie Haggerty shine within her very limited range. The one false note is Roberts, who was always tolerable when relegated to playing Allen’s sidekick but just isn’t that good of a film actor and whose beats always feel a little forced here. But nothing he does is enough to ever disrupt the ensemble’s seemingly effortless momentum.

Allen shows an increased mastery of film technique as well, with that new-found confidence carrying over into an increasing reliance on lengthy master shots, which reinforce the film’s ensemble nature while also lending it an appropriately pastoral rhythm. The Allen of his earlier movies would have been unable to pull off the extended exchange where Steenburgen confronts his character about lying about Farrow, which is masterfully blocked and performed.

This is just about the last film where Allen allowed his character to be well-rounded and witty, for some reason opting to just spew jokes via a borderline caricature from that point on. I’m not sure why he wandered off down such a self-defeating path—it’s obvious from the documentary Wild Man Blues that he was still capable of ringing resonant changes on the persona he’d so carefully wrought—but Sex Comedy pretty much represents the swan song of the Woody who defined an era.

Now, about that ending: Allen does an unimpeachable job of establishing the atmosphere, then setting the tone, then introducing the characters, and then setting the various interactions in motion, fleshing out the characters along the way. And all of that is so delicious and, yes, charming that it makes it that much more dispiriting when you have to deal with the train wreck of the final act. My surmise—and I’m really winging it here—is that working simultaneously on Zelig prevented him from seeing the flaws in the Sex Comedy script and likely kept him from doing the kind of reshooting that allowed him to elevate many of his other films from pedestrian or confused to extraordinary.

Had he been able to solve the puzzle he created for himself, Sex Comedy would have easily ranked up with Annie Hall, Manhattan, and Hannah in the mass mind. But anyone who hesitates because of what they’ve heard, or who has heard nothing at all about this film, is missing out in a big way. This is what a great movie feels like when it feels like it doesn’t need to strut its stuff. A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy is so light and energetic and infectious, it’s like a bracing tonic—the cinematic equivalent of a good saison. It moves and feels like no other film. It’s Allen’s most underrated work—and it’s a much needed infusion of summer light during what is, in many ways, the darkest time of the year.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | The Blu-ray-quality HD presentation is really, really good, making it hard to find any serious flaws—not that you couldn’t find problems if you really wanted to hunt for them but nothing ever happens to pull you out of the film, which is all that matters at the end of the day.

SOUND | It’s not like Woody Allen makes silent movies and audio doesn’t matter—the all-important dialogue can be clearly heard, the mix helps create atmosphere in the scenes, and the music cues carry an appropriate weight. But it’s all in modest service of the material, as it should be.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC