review | A Woman Is a Woman

Probably Godard’s most accessible film, this remains a charming dissection of the American musical—and an indispensable record of Paris in the early 1960s

by Michael Gaughn

June 4, 2022

Watching a Godard film is a lot like taking an exam in 20th-century philosophy administered by a brilliant but sadistic college professor. No matter how certain you are of your answers, he will always find some fiendishly abstruse and cryptic way to prove you wrong, relishing making you feel like a dope in the process. Godard is the film snob’s equivalent of a secret handshake, the thing the cognoscenti deploy to mock and spit on the peasantry.

And it doesn’t help that his work became more and more harsh and inscrutable as the ‘60s went on, until he reached his Vertov Group period, doing highly politicized, abstract films in collaboration with Jean-Pierre Gorin that are for the most part both wearisome and gratingly coy.

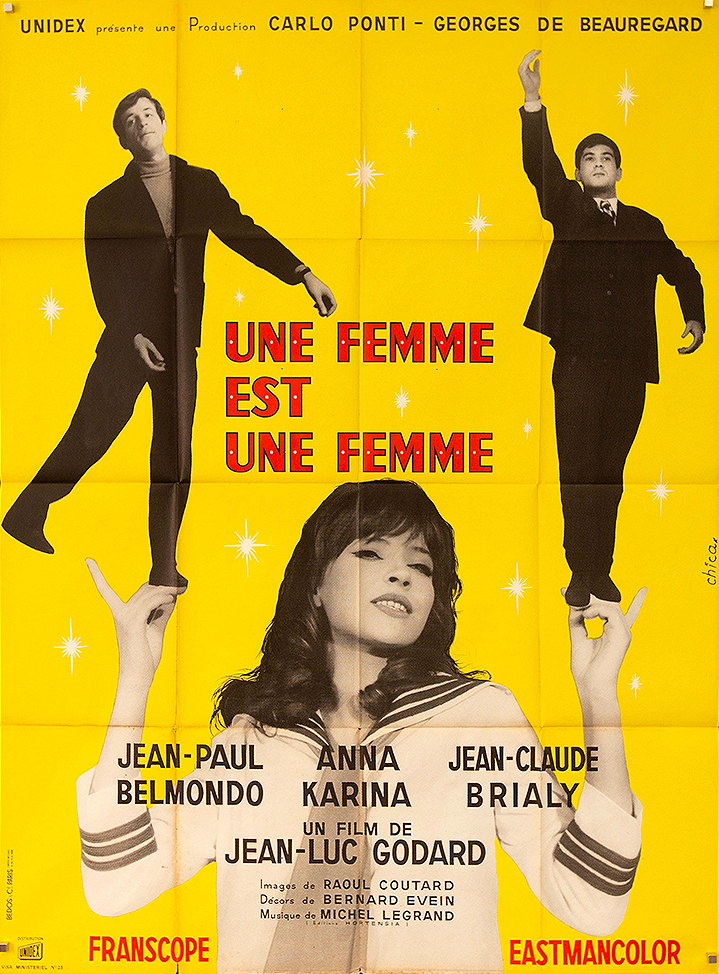

But there is still that initial period of the early ‘60s where, yes, he was aggressively and blatantly reinventing cinema, but he was doing it playfully, with abundant energy and wit, not yet embarrassed by his obviously sincere romanticism. Films like Bande à part, Contempt (Le Mépris), Alphaville, and Pierrot le Fou remain fresh and unmatched and, from beginning to end, exhilarating. Maybe the most accessible of that early batch is Godard’s riff on the Hollywood musical, as a way of riffing on the whole artifice of movies, A Woman Is a Woman (Une femme est une femme).

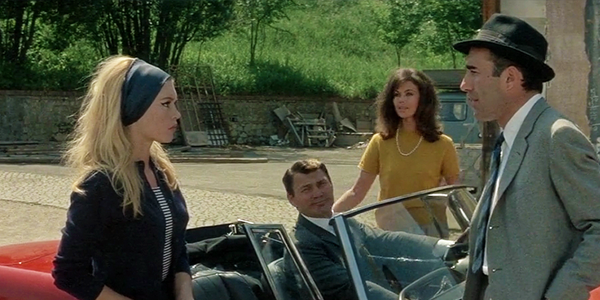

You don’t need to get film-school analytical to explain the joys of this movie. It’s easier to just tick them off: Anna Karina, who the camera (and clearly Godard) loves and who devours the camera in turn; Raoul Coutard’s véritê shooting style, in subtle but evocative Eastmancolor, which keenly documents early ‘60s Paris without turning it into a series of postcards; the gags, which are admittedly quirky and smartass but still startlingly funny; and that constant playing with and questioning of film technique, which somehow hasn’t dated a day and energizes the movie in a way that can never be done by coloring within the genre lines.

Godard was always a radical, but he was a radical who knew he had a large international audience, especially in America, and while his affection for American culture soured as the ‘60s went on, and while his skepticism is apparent throughout A Woman Is a Woman, he also knew Hollywood was the lingua franca of moviemaking at the mid century, and you can sense he’s almost in awe of what it was able to churn out.

This is probably best on display in the long scene where Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo sit at a table in a small cafe while she struggles with whether to sleep with him to spite her live-in boyfriend. It’s all very New Wave-y with a lot of oblique comments and a lot of jump cuts. But then Karina asks Belmondo to play a Charles Aznavour record on the jukebox, and the movie basically just stops for three and a half minutes while the tune plays out. Yes, that was revolutionary for the time, and is still radical because, unlike the theme-park experience of most contemporary movies, which essentially straps you in for the duration then guides every millisecond of the ride, inducing carefully graduated jolts along the way, Godard wants you to use that caesura to inject your own thoughts and feelings into the film, to essentially collaborate with him—which is why A Woman Is a Woman can never be the same for any two people who come across it, or for any one person viewing it more than once.

But that moment, by leaning on pop music, is also very Hollywood, is Godard knowing that, if he was going to unravel the fabric of the typical movie-watching experience that drastically, he needed to toss a sop to make it palatable. Sadly, his subversive impulse here would, like everything, be ultimately coopted and corrupted by mainstream filmmaking, leading to the now pervasive use of pop songs as a crutch to cover up the filmmakers’ basic lack of creativity (and feeling).

But you don’t have to watch A Woman Is a Woman at anything approaching that level to enjoy it. Even skimming its surface brings pleasures you won’t find elsewhere. Coutard’s cinematography is groundbreaking, justly famous, and remains sublime. There are salient examples everywhere but a couple of the most striking (both night shots) are Karina and Jean-Claude Brialy standing in front of a shop window with “Lancome” in white neon behind them and Brialy stepping out onto the apartment balcony with the boulevard lights floating off into the distance. The former is very much like what Russell Metty was doing in Douglas Sirk films like All That Heaven Allows, but shot simply, on location, without soundstages or lighting grids, and with a documentary-size crew.

And while Amazon Prime’s presentation isn’t the last word—you long for a 4K release while praying nobody will be dumb enough to attempt what currently passes for a restoration—it’s so true to the elegant grit of the original film that very little is lost by watching it this way. The colors are rich but never over pumped, and the subtlety of the gradations—essential to presenting this film—is for the most part maintained. It’s legitimate to hope something better will some day come along, but it will need to be significantly better than what’s offered here to mean anything at all.

The audio isn’t pristine, but it wasn’t at the time, and the patina of the era—reflected in the heavy reverberation in a lot of the music cues—is essential to the film’s impact. Putting the score on an equal footing with the dialogue and then bringing cues in and out like he was arbitrarily flicking an on/off switch was a big part of what Godard was after, using the lulling reassurance we usually take from wall-to-wall film music to yank us out of our complacency—kind of like taking a toy from a baby to ultimately return it in the end. So, while the score isn’t very well mixed by contemporary standards, it’s actually a stunning mix if you’re focusing on the needs of the film, which is as it should be.

There’s only one real irritant here: The size, thickness, and black border around the subtitles, which are all out of scale and a constant distraction. Retaining the original crappy-looking titles baked into the print would have been a huge improvement all the way around.

There is really only a handful of movies that qualify as true classics, a number small enough to rest comfortably in the palm of your hand; films that transcend the zeitgeist, fleeting emotional attachments, and the aura created by relentless marketing and that tap into far deeper and more sustaining currents than the vast majority of fare. This is one of them. But given the aversion, which still persists, to foreign films—or at least to the ones that don’t try to ape American films—it’s necessary to make the case a little more forcefully here than you have to for the Hollywood standards. So let’s try this: You can’t say you know and love movies if you haven’t at least tried Godard. And possibly the best place to begin that journey is the current release of A Woman Is a Woman.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Amazon Prime’s 1080p presentation isn’t the last word but it’s so true to the elegant grit of the original film that very little is lost by watching it this way

SOUND | The audio isn’t pristine but does a serviceable job of maintaining the patina of the era, which is essential to the film’s impact

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC