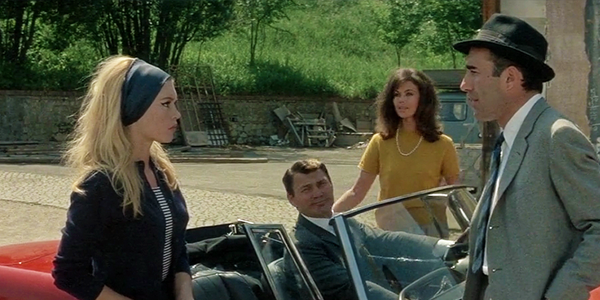

review | Alphaville

Who knew Godard’s future would turn out to be our now?

by Michael Gaughn

June 29, 2022

The question I constantly wrestle with when reviewing an older film is why anyone should care about the movie if they’re not already on its wavelength. The point of reviewing isn’t to share you personal favorites list with the reader, with a kind of take-it-or-leave-it attitude about whether they’ll actually enjoy it. Worse is the reviewer who just piles on, merely echoing the blind conformity of the herd. The only reason to write up any film, old or new, is to create what you hope is common ground with the reader, to give them a glimpse of what you appreciated (or disdained) in the hopes they’ll seize the ball from there and run with it, having their own experience, not just a carbon copy of your own.

Any truly sentient creature in the present should find plenty to pick up on in Alphaville. It’s probably the only valid glimpse of the future ever committed to film, riding joyously, for all its dire predictions, on the back of pulp fiction and sci-fi—and, it needs to be pointed out, given how quickly and completely Godard would soon turn against Hollywood, American pulp fiction and sci-fi.

Most visions of the future latch onto the technology, trying to second guess how science will develop—which will always be a sucker’s bet—and the characters, even when they adopt what seem to contemporary audiences odd behaviors, are always us just projected into the future essentially unchanged from who we are now. (Hello!—all you Star Trek fans out there.) What Godard does instead is anticipate the elaborate, increasingly lopsided dance between human nature and its extension in technology, with his focus squarely on the human, and, in truly uncanny ways, anticipates our rapid devolution and the world of the present, awash in a drowning tide of lost souls.

Some of his more cogent prognostications:

—The rise of the myth of the eternal present, which blocks people from considering the past or the future so that, as dire and empty as it is, the current state of things seems like the best of all possible worlds.

—Reducing culture to our most primitive urges to make it easier to control mass behavior. (Anybody who disagrees this has come to pass hasn’t been paying much attention to blockbuster movies, recent politics, or Facebook algorithms.)

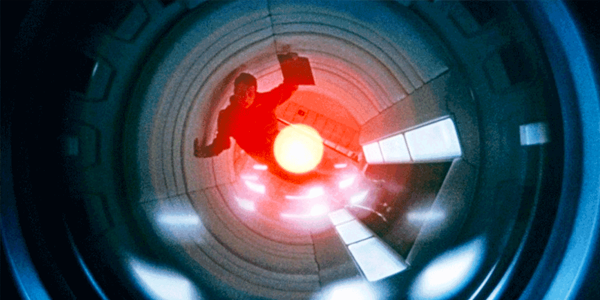

—Embracing and fetishizing that Western science is only superficially rational and objective and is driven, more than anything else, by the idea of purging Original Sin. (As the movie’s supercomputer intones: “The acts of man through the centuries will gradually, logically destroy him. I, Alpha 60, am merely the logical means of this destruction.”)

The list of searing insights is much longer than the above, but this will give you the drift. Of course, my descriptions are too reductive and nothing but a travesty of what Godard actually wrought—but the point is that, his gaze steely, and undistracted by positivism and other hucksterist notions of progress, he got it all frighteningly right.

It’s not the job of any film to predict the future, of course, or be any kind of handbook or teachable moment or push any kind of social agenda. That’s the antithesis of cinema. Godard was resonating to something he sensed in the air—the imminent disappearance of the poetic soul—in other words, the soul—and worked to express that almost inexpressible event as accurately and evocatively as he could.

I know: I’ve made this all sound very cerebral and dry and bleak. It’s not—Alphaville is a truly fun film that, like all early Godard, has cinematic thrills, both big and small, in virtually every shot. And, as with A Woman Is a Woman and Contempt, he underlines at the very beginning that this is “just” a film, with the computer telling us about the importance of legend for disseminating fictions to the masses—thus providing a typically paradoxical justification for the movie’s crime-fiction and sci-fi trappings. And it’s easy to confuse Godard’s exploiting of comic-book conventions, with their broad-stroke ideology and cheap sentiments, as his own thoughts and feelings, but that’s all part of his effort to keep you off balance so you keep questioning and paying attention.

Watching Alphaville in SD on Amazon Prime, I was surprised by how good parts of it looked. Then I watched it in HD on iTunes, and I saw the same cinematography bloom. The 1080p version is murkier than the SD stream, with more contrast and with the blacks more crushed, but the additional resolution allows for more subtle gradations—something Godard and Raoul Coutard took full advantage of and which is fundamental to appreciating the film, and that isn’t even hinted at in the lower-res version. There are closeups of Anna Karina that have a richness and subtle glow reminiscent of the best black & white portrait photography, and that contrasting of the luminous with the harsh is key to conveying her position as a pod-person-like succubus who’s also the possible vessel of human salvation. The film’s famed rendering of the striking but cold interiors of modern office spaces feels bracing, almost seductive at 1080p, falls flat in SD. I don’t know if a good 4K transfer could open up the images even more, but I’d be curious to find out.

This is a particularly nuanced mono mix so polyvalent it reminded me of Phil Spector’s ability to convey layers and layers of depth in a single channel. Crude to today’s jaundiced ears, all that really matters is whether it expresses what Godard meant it to express, and it does. The strange sense of Alpha 60’s voice and the society’s electronic communications being in the immediate foreground while sounds of the actors and their environments sit in the mid ground is unsettling. And Godard’s signature mucking around with what ought to be diegetic sound—for instance, the sound of the perversely brief fight scene soon after hero Lemmy Caution checks into his hotel room suddenly drops away when Godard cuts to an angle through a window, but the music playing within the apartment continues on—comes across with plenty of presence. But also with a decent amount of distortion—but that’s OK. It rings true.

The on-set sound is very raw, full of the reverberations of the spaces, but that adds to the documentary-like sense of immediacy—the reality of this clearly fictional but sadly plausible world.

You don’t have to watch Godard to see Godard. There is hardly a film made since the early ‘60s he hasn’t influenced in some way and, with their relentless efforts to appropriate because they lack the emotional depth to actually create, many contemporary directors now mimic his tropes verbatim. But the distance between innovator and imitator couldn’t be greater—kind of like having a burger at Applebee’s instead of Boon Fly Cafe. There’s a resemblance, but the resemblance is probably the least meaningful thing about the experience. Applebee’s is safe, predictable, bland; dead, not alive. And so it goes with Godard.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | In 1080p on iTunes, the film is a little murky, with crushed blacks, but the resolution allows some of the images to look properly subtle and rich, creating the necessary contrast between luminous and harsh

SOUND | The mono mix is unusually nuanced, helping to convey the unsettling juxtaposition between the omnipresent supercomputer and the spellbound citizens

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC