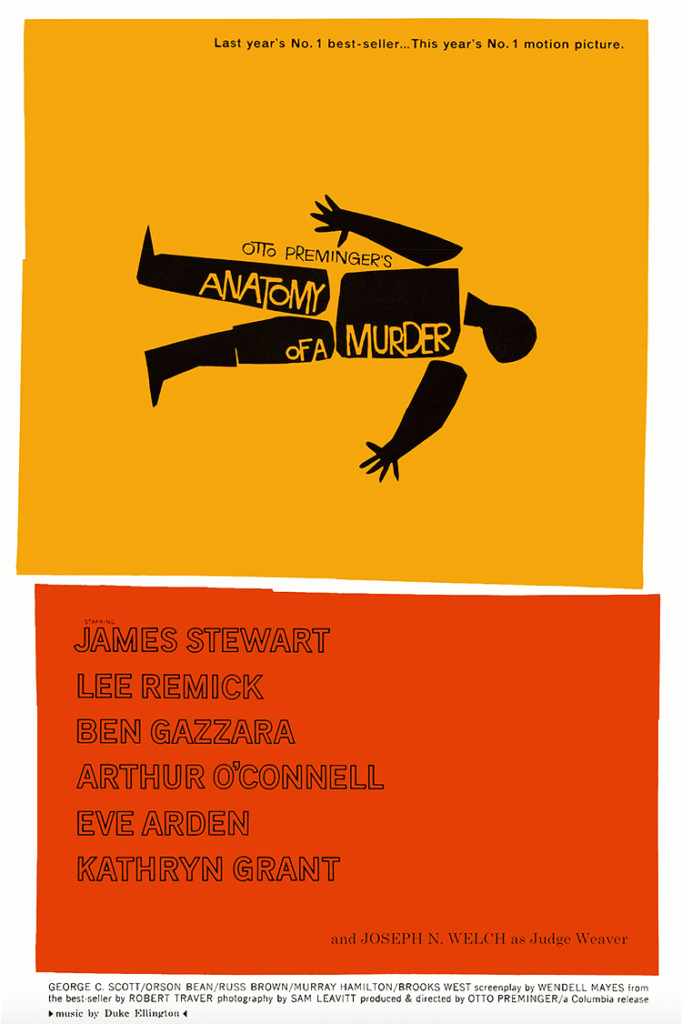

review | Anatomy of a Murder

Held together by Jimmy Stewart’s career-defining performance, this epic-length courtroom drama looks exceptionally good in the 4K HDR

by Michael Gaughn

December 23, 2022

The second American Renaissance (c. 1955 to 1962) spawned a whole slew of mainstream iconoclasts. Coltrane, Mingus, and Monk in jazz, Weegee in photography, Warhol in art, Glenn Gould in classical music, Lenny Bruce in comedy, Ginsberg in poetry, and Aldrich, Kubrick, and Sirk in the movies all stand at the beginning of the long and fecund list that sums up the tenor of that time, an era that coughed up more cultural radicals than any other.

Director Otto Preminger was a provocateur, a bad boy, but he was never an iconoclast. He very much wanted to be seen as being a member of that club but his interest in transgression didn’t run deep. He was mainly interested in breaking taboos as a way to grab headlines and fill theater seats. At the end of the day, he was a guy who made the occasional intriguing film but was essentially a workmanlike director with a penchant for publicity.

All of which makes it curious that his Anatomy of a Murder has just received a 4K HDR release. I could name a couple hundred movies that deserved that attention long before Anatomy. The way titles are chosen for 4K is so random it almost feels like it’s being done by lottery.

To be clear, I actually like Anatomy of a Murder. I’ve liked it ever since I was a kid and sneaked downstairs late at night to watch it once everyone else in the family was asleep. And it always held my attention, even at its almost three-hour run time and arbitrarily broken up by a seemingly endless number of commercials. It’s a talky film, a courtroom drama that takes almost a whole hour to get to the courtroom, and yet somehow works, despite problems—partly because it was made at the right moment in time so that the whole of the culture helps prop it up, but mainly because of Jimmy Stewart.

To start with that propping up, Anatomy springs from the trend toward gritty documentary-style dramas that began with The Naked City in 1948 (which were themselves inspired by the Neo Realist films out of post-World War II Italy). That style really didn’t take root until the mid ‘50s, only to be erased by the emerging tumult of the early ‘60s, to then re-emerge, more heavily stylized, in the early ‘70s in movies like The French Connection, Taxi Driver, and urban exploitation films—only to be once again obliterated, likely forever, by the emergence of fantasy and blockbuster movies in the late ‘70s.

Anatomy has a down-at-the-heels look appropriate to a small industrial city in Michigan in the late ‘50s. Shot on location, nothing was done to spruce up the decay that had begun to envelop the country as the post-war boom began to fade. That tack can make many films of the era feel just tawdry and depressing but it works here because the actors bring a heightened enough presence to the action to offer sufficient relief from the gloom—though it has to be pointed out that they overdid it with Stewart’s house, which is so relentlessly filthy it’s hard to believe somebody like Stewart would ever live in a dump like that.

Casting was never Preminger’s strong suit, so what you get here is incredibly hit and miss. Arthur O’Connell and Eve Arden do what they can with the hoary clichés of the alcoholic, washed-up attorney eager for redemption and the wisecracking underpaid and unappreciated secretary. Joseph Welch does an outstanding turn as the crotchety but droll and benign judge. And Murray “Mayor Vaughn” Hamilton is estimable as ever in his patented role of arrogant and put-upon schlemiel. You can only feel sorry for Brooks West as the easily duped district attorney—the weakest link in the script and casting, who’s present just to be Stewart’s straw man. And while Lee Remick constantly grabs the camera’s attention, even in the crowded courtroom scenes, it all comes a cropper whenever she has to open her mouth and attempt to act.

Adding to the challenge is the use of locals as extras, who are fascinating to look at because they’re unvarnished reflections of the time. But the distance between them and that teeming gaggle of Hollywood actors is so extreme it almost topples the artifice by making clear the near infinite distance between those two worlds.

But, again, Anatomy is really all about Stewart, who was that rarity of being as much actor as star and throughout the ‘50s brought a maturity to his roles that audiences weren’t used to seeing from A-listers. His ability had always been evident—his performance in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington takes Capra’s precious, flawed bromides to a level he was never able to achieve via other actors—but Stewart, by sublimating his experiences in World War II, heightened movie acting in a way that’s never fully been appreciated.

What he accomplished here is truly a feat—holding together an epic-length film that’s almost all dialogue by his performance alone. It’s especially fascinating to watch him take his evolved version of classic movie acting and use it to go toe to toe with Actors Studio types like George C. Scott and Ben Gazzara, who both, in their “we’re too good to be here” way, attempt to devour most of the scenery. There’s something about Stewart not only being able to single-handedly hold the picture together but dispatch these upstarts without breaking a sweat that’s both exhilarating and triumphant.

Anatomy of a Murder looks damn good in 4K HDR—especially for a production that deliberately didn’t have a lot of polish. While there’s the constant bugaboo of elements on either side of dissolves looking compromised—especially problematic here since Preminger tended to rely on longer takes—they’re never quite as awful as the similar elements in Creature from the Black Lagoon. Anatomy, for the most part, looks like film, making it easy to stay immersed in the movie. While it’s neither as faithful or compelling as the transfer for Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, nothing happens along the way to jolt you out of the experience. The quality of the transfer is especially evident in many of the medium and tighter shots, where you really couldn’t ask for anything more. The one significant nit is that the HDR grade does occasionally make shots look a little plasticy or video-like—a fleeting annoyance; nothing persistent.

The audio is for the most part clean and well balanced—although there’s a scene in Stewart’s house near the end that’s oddly several dB lower than everything around it. The only times the dynamic range really comes to the fore are when Duke Ellington’s band is strangely grafted into the movie, which sound fine but really don’t add anything to the overall impact. I do once again have to point out that this is yet another older film where the original mono mix is nowhere to be found. I don’t understand the point of getting the look of a movie within striking distance of how it was originally presented and then playing fast and loose with the audio.

This might be the simplest and most definitive conclusion I’ve ever written: Watch Anatomy of a Murder just to savor Jimmy Stewart at the peak of his powers. This a sly act of virtuosity done with modest, almost humble, bravura by a performer too often enjoyed but not appreciated, too often passed over as just a comfortable old shoe. There is everything to be learned about movies and movie acting by watching Stewart rise so far above both the material and its execution and do the impossible without ever once succumbing to the temptation to pat himself on the back.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC