review | Blue Jasmine

Woody Allen’s best late-period work is an almost perfectly balanced drama that still resonates almost ten years on

by Michael Gaughn

February 8, 2021

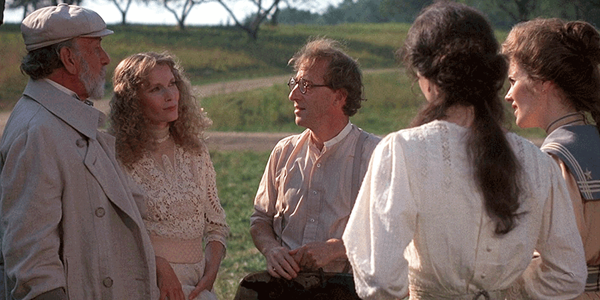

Fast forward 30 years from the last Woody Allen effort I reviewed, 1982’s A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, and you arrive at Blue Jasmine, his best late-period work and the film that nabbed Cate Blanchett a Best Actress Oscar. That at first glance it can be difficult to see the common DNA between these two movies shows how much Allen evolved as filmmaker over the decades and helps dispel the jaundiced myth that he is little more than an assemblage of mannerisms treading in a rut.

What isn’t a myth is that Allen has struggled ever since his break with Mia Farrow after 1992’s Husbands and Wives. He earned much praise for Match Point (2005), but that film is ultimately undone by its implausibility, and its success can mainly be attributed to the public’s fascination with the bright, shiny Scarlett Johansson. Midnight in Paris (2011) was celebrated as a return to form, and made Allen a crapload of money, but it’s basically a lazy recitation of his greatest hits that’s ultimately thinner than fast-food coffee. Wonder Wheel (2017) earned Kate Winslett some kudos (but the real standout is Jim Belushi, who’s so good it’s shocking) and the film almost works, if you’re willing to roll with its early acts, but is ultimately a noble failure.

Of the later films, Bullets Over Broadway, Mighty Aphrodite, Vicky Christina Barcelona, the dramatic sections of Melinda and Melinda, and, much more modestly, Cafe Society, join Blue Jasmine as the ones worth a good look. (I’ve been trying to see the Sean Penn vehicle Sweet and Lowdown for years but it flits in and out of circulation so arbitrarily that I’ve never been able to seize the opportunity on the rare occasions when it’s bobbed to the surface.)

Jasmine exists at a higher level than any of his other late-period work, on par with the much earlier Annie Hall, Manhattan, Stardust Memories, Broadway Danny Rose, and The Purple Rose of Cairo. But it’s not easy to pin down why everything suddenly clicked here. Unlike his other masterworks, it’s not a comedy, although it does have some humorous touches. The Allen persona is nowhere to be seen, even in surrogate form. And even though he has an incredibly uneven track record with dramas, Allen shows an effortless command here.

I suspect many would attribute its success to Blanchett, but that shows a fundamental ignorance of how movies work. She didn’t write the script, plan or execute the shots, or labor in the editing room. Without that elaborate support—which is essentially the entire edifice of a film—a performance, no matter how good, isn’t worth bupkis. I think the success of Jasmine, and the reason Allen rose to the occasion, can be actually attributed to class. But I’ll get to that.

Blue Jasmine exhibits a bounty of great acting, and it’s not really possible to appreciate the film without first considering Allen and actors. From the late ’70s on, and even in his subpar efforts, Allen has offered a place where actors can show their abilities without fear of being humiliated, relegated to reciting genre cliches, treated like the director’s marionette, or subjugated to green screen. Because he provided an oasis, a place where an actor’s abilities were treasured and given room to flourish, a tremendous diversity of talent flocked to his projects—that is, until Me Too happened (but we’re not going to go there again).

(It’s ironic, by the way, that someone with no traditional training turned out to be the best actor’s director of the last half century.)

What’s always intriguing about Allen is that he can get me to appreciate performers I can’t stomach elsewhere. I wouldn’t want to spend a nanosecond with Andrew Dice Clay outside the boundaries of this film, and yet he’s perfectly cast here. Pretty much the same can be said for Louis C.K., who’s insufferable as a comedian and elsewhere only borderline acceptable as an actor. (He does do a strong turn in American Hustle, though.) Here he shines. Ditto for Alec Baldwin, who’s become a caricature of himself over time but rises above his limitations in Jasmine.

Other standouts: Bobby Cannavale (Boardwalk Empire) brings depth and some surprising twists to what could have been a thuggish performance as Sally Hawkins’ boyfriend. And Michael Stuhlbarg, who out and out stole Men in Black 3 as the pixieish multi-dimensional alien Griffin, is far more understated but still strong here.

As for Blanchett: As one of those performers, like Penn and Streep, far better at “acting” than acting, I’ve always found her work rough going—her attempt to play Katherine Hepburn in The Aviator was so cringeworthy I wanted to avert my eyes from the screen—but she is perfectly in sync with Allen’s material and makes a potentially unsympathetic character compelling. And while Blanchett got most of the attention, Hawkins—another actor I could usually take or leave—I think actually bests her here.

The two weak spots in the chain are Peter Sarsgaard, who just doesn’t bring enough heft to his role as the aspiring diplomat, and Alden Ehrenreich as Blanchett’s son, who barely registers as a presence.

About the whole class thing: Allen has taken a lot of heat over the years, some of it justified, for being overly enamored with Upper East Side society. And a lot of his portrayals are so fawning they take on a peepshow quality for almost every human being on the planet who wasn’t to the manor born. But the 2008 recession caused him to put all that in perspective, and Blue Jasmine is a perceptive, even biting, look at the great class divide that doesn’t have an ax to grind for either side—and thankfully doesn’t fall into the oppressive cliche of saying the members of the lower classes are forever doomed to do themselves in. It’s his ability to pull from his vast experience with both sides of the class equation without peddling an agenda that allows him to go deeper than most mainstream attempts to fathom the issue.

(Let me pause to note that Allen is one of the last filmmakers left from the era before you had to be a member of the top one percent to gain admittance to Hollywood, when lower-bred outsiders were at least tolerated as long as their movies made money, when they could still have a voice.)

Blue Jasmine looks really, really good in Blu-ray-quality HD—which I suspect can attributed to the existence of a DI. I was hard pressed to find any serious flaws—not that you can’t find problems if you really want to hunt for them, but nothing that was happening with the images ever pulled me out of the film, which is all that should matter at the end of the day. My one criticism is the introduction of too many golden tones in post. Yes, I get where they were going with that, but I still suspect that future generations are going to look at the early efforts of digital filmmaking and want to slap us silly for not being able to resist fiddling with the knobs.

And now I once again come to the pointlessness of talking about the audio in a Woody Allen film. It’s not like he’s making silent movies and audio doesn’t matter—few directors rely as heavily on dialogue—and it’s not like the mix doesn’t help create atmosphere in the scenes; and it’s not like music cues don’t have a huge impact in his work. The point is that the audio is in modest service of the material, as it should be—there are no bravura flourishes that would make you exclaim “Nice audio!” So let’s just say that it works, and works well.

You don’t need to know anything about Allen’s other films to appreciate Jasmine, but saying that at this moment in time sounds defensive and weak. Allen has created a tremendous and unparalleled body of work, one that deserves to continue to be appreciated. Few directors are capable of making movies that are as human, and Blue Jasmine, as a study of pride and vulnerability, might be his most human film of all.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | The Blu-ray-quality HD presentation is really, really good, making it hard to find any serious flaws—not that you couldn’t find problems if you really wanted to hunt for them but nothing ever happens to pull you out of the film, which is all that matters at the end of the day.

SOUND | It’s not like Woody Allen makes silent movies and audio doesn’t matter—the all-important dialogue can be clearly heard, the mix helps create atmosphere in the scenes, and the music cues carry an appropriate weight. But it’s all in modest service of the material, as it should be.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC