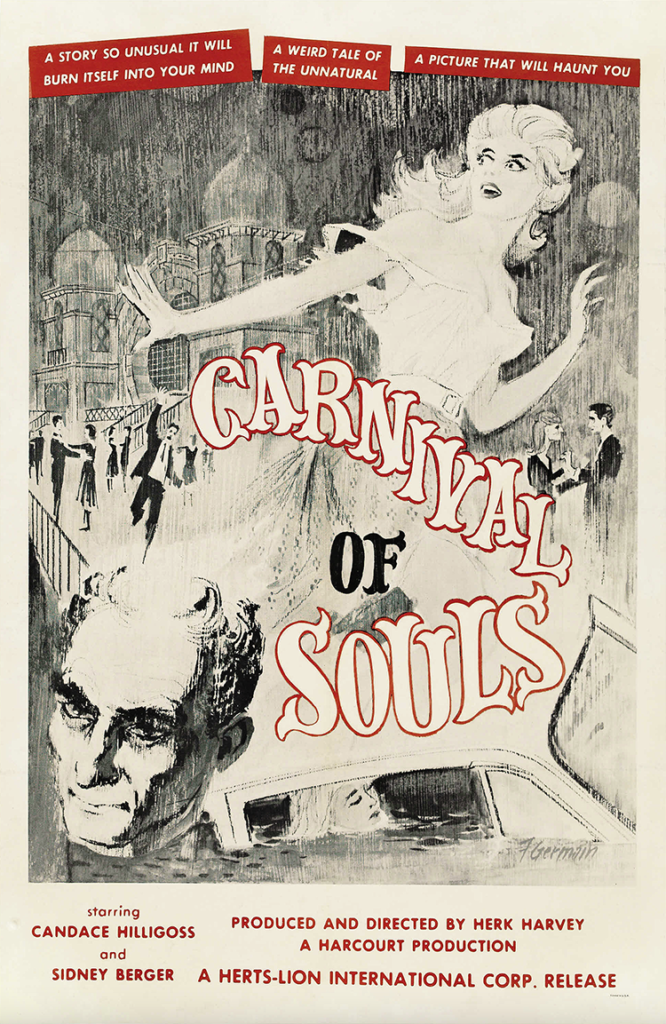

review | Carnival of Souls

Given how it was made, this classic horror movie shouldn’t be a classic, or even a movie, and yet it remains one of the most influential films to come out of the genre

by Michael Gaughn

October 10, 2022

If the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a B movie, then Carnival of Souls is a solid C—a wild fling at moviemaking by a bunch of naive and repressed Midwesterners meant for second, or third, billing at Kansas drive-ins, a kind of Bergman-goes-to-Topeka thing that must have confused the hell out of the 2 a.m. hangers-on expecting to get off on something like Chain-Gang Girls. And yet somehow out of that impossible equation came art.

To give a quick, urban-legend take on its genesis for those unfamiliar with the film, Herk Harvey, a staff director at Centron, best known for its ‘50s industrial-arts and hygiene shorts, stumbled upon a Bergman film, which inspired him to take his one and only stab at feature filmmaking by grafting European art cinema onto the American exploitation horror movie, the whole thing done on zero budget. By rights, the result should have been a disaster, and in some ways it is; and yet, miraculously, out of that compost heap emerged a very beautiful and, in the best sense, haunting little film.

(Just so it doesn’t sound like I’m unfairly dumping on the decidedly staid Centron, it was something of a filmmaking powerhouse, within its lane, and the place where Robert Altman got his start.)

The best explanation for why Carnival of Souls works is channeling. The filmmakers, by their own admission, had no idea what they were doing so they had no choice but to surrender to what was in the air. And the cultural winds were so strong at the time that they ultimately steered Harvey and his team safely into a very snug little harbor.

This is completely naive, seat-of-the-pants filmmaking—the kind of thing a lot of us hoped would become legion in the wake of camcorders and cellphones and The Blair Witch Project, but we got a bunch of unimaginative dolts aspiring to make superhero movies instead. By aping arty gestures without understanding them, Harvey and friends were somehow able to conjure up a film that bears an uncanny resemblance to Polanski’s Repulsion (which was three years in the future at the time) and that can actually pretty much hold its own against that other more carefully crafted and deeply felt film.

Souls’ ineptness is actually a virtue. Taking a trained New York actress and dropping her in the middle of a bunch of well-intended but obviously unsophisticated Midwestern actors heightened the sense of the main character’s extreme alienation. A lot of the movie’s justly famous atmospherics can be attributed to the disparity between the onscreen action and dubbed dialogue that sounds like it was recorded in somebody’s closet. The Foley work consistently maintains an earth-to-Alpha-Centauri distance from whatever it’s trying to enhance or depict. And only about a quarter of the shots work but they’re just strong enough to keep the film from unraveling completely. This is a movie held together with chicken wire, spit, and a prayer.

That lays bare a fundamental truth about all mainstream filmmaking, no matter what the budget: The audience almost always contributes at least half the experience of a movie—sometimes considerably more. Producers figure out what people will respond to and then provide just enough emotional and intellectual triggers to allow audience members to fill in the blanks with their own projections. That explains why most films have no staying power—people move on to new fads and preoccupations, so they’re no longer able to bring anything relevant to watching the film. It also explains why most movies that do hang in there are wrapped in a nostalgic glow—because the viewer has commingled it with the emotional resonance of their own memories from the time they first saw it. It also helps to explain why franchises—the safest and least creative moviemaking bet there is—have spread like the plague.

That’s not to say there isn’t a substantial movie here. Candace Hilligoss somehow managed to craft a legitimate performance while having to contend with throw-it-at-the-wall direction and lousy continuity. You keep wondering if she’ll be able to bring any consistency to her character but then the roadhouse scene happens, where she convincingly conveys the sense of clinging to whatever shred of reality she can find because she knows letting go will mean she’ll disappear forever. I didn’t realize until this viewing how much of what’s best about Souls can be attributed to Hilligoss. They could have pulled off all the spooky atmospherics they wanted but none of it would have mattered if she hadn’t been able to rise several levels above the material and the circumstances. That makes it all the more amazing that the filmmakers were able to create a powerful and fairly nuanced portrait of radical dissociation while having no real grasp of their own subject matter.

There’s something—a lot—to be said for naivety. Movies have gotten thinner and thinner—and longer and longer—as each successive generation has found the basics of film technique working their way deeper and deeper into their DNA. Practically every sentient being now knows how to make a presentable movie. But it’s become almost impossible to find anyone who knows to how to do anything meaningful with the tools once they’re given to them. I realize it’s an impossibility, but a new take on cinema that took its cues from Carnival of Souls wouldn’t be the worst thing that could happen to us—not by a country mile.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

SOULS ON PRIME

I know it’s my job but I don’t know what to tell you about the UHD presentation on Prime—mainly because this is such an unorthodox film it’s hard to know what matters. Although it’s been repackaged in all kinds of ways, Souls has never looked great—and, given the shooting circumstances, it’s not hard to understand why. To say that watching a subpar version can add to the creepiness is true up to a point, but it’s also a bit of a cheat. I’d prefer to see something that comes as close as possible to what Herk Harvey actually shot.

This presentation doesn’t do that. Yes, it’s UHD but it’s been processed with such a heavy hand that everything looks waxy. Occasional shots do look exceptional but it’s frustrating to have them be the exception and not the rule. All I can say is that, if you can get onto this film’s wavelength—something that can be hard for the increasingly jaded to do—the presentation isn’t likely to have much impact on your experience one way or the other, which is praising by faint damning.

The last thing I want to do is find myself in the middle of an aspect-ratio pissing contest, but the film is presented in 1.37:1—the ratio of the negative and how the usually definitive Criterion has chosen to offer it as well. But IMDB says it was meant to be seen at 1.85:1, which, if true, helps to explain what seem like some unusually bad compositions and why camera gear appears in the top of the frame during the whirling dancing shots near the end. I can’t say it ought to be shown 1.85 because I’ve never seen it that way—just curious why it’s not.

—M.G.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC