review | Double Indemnity

The film that birthed a genre and put a serious dent in the Hays Code, this Wilder/Chandler masterpiece still holds up—but could use a major restoration

by Michael Gaughn

August 30, 2022

The definition of film noir is really simple and unambiguous—and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Noir is always about a schnook—a guy who’s full of himself and thinks he has the world by the tail only to find out, the hard way, that the world has got him firmly by the balls instead. There are no exceptions to this rule. People like to muddy the waters by conflating noir with stuff like crime dramas, psychological thrillers, horror films, and—Lord help us—goth, but if it doesn’t adhere to the above stated formula, it’s just not noir.

And noir, indisputably, began with Double Indemnity. And while Indemnity is as much the effort of Billy Wilder and, by supplying the source text, James M. Cain, it is best seen as an expression of the spirit of Wilder’s collaborator on the screenplay, Raymond Chandler. What’s best about Indemnity is all about Chandler and his preoccupations and his worldview. So it follows that Chandler, with an able assist from Wilder and Cain, created noir. I don’t see any good reason to believe otherwise.

Indemnity still works, at this late date, because the film is as lean and focused and witty and ingeniously crafted as Chandler’s printed prose. It’s a sordid drama, full of truly unappealing characters doing unspeakable things, but everyone expresses themselves with such verve and the wryly sardonic undercurrents are so constant and strong that you leave the experience feeling giddy instead of soiled.

It’s audacious from beginning to end but never gloats or otherwise shows off, instead taking that carefully honed script—which some consider, not without cause, the best ever written—and using it as not just a guide or a foundation but a bible. Wilder would almost match Indemnity six years later with Sunset Boulevard, but the latter just doesn’t have the redeeming grace Chandler brought to Indemnity. And Wilder’s career would be, from that point on, nothing but a slow slide down from the pinnacle of those two dramas—which really aren’t dramas, in the traditional sense, at all.

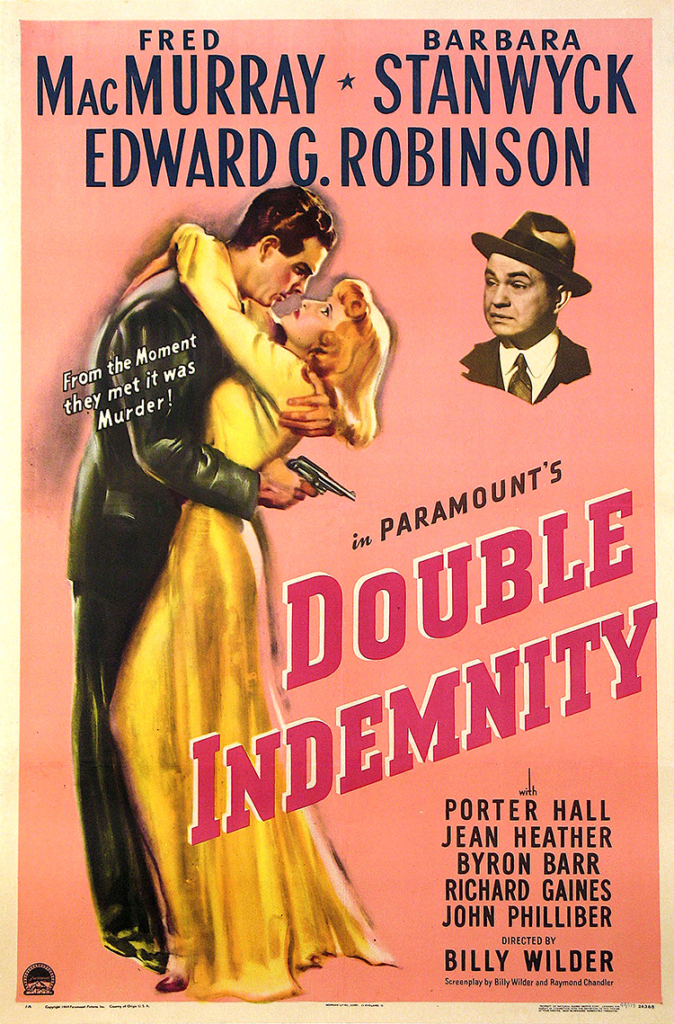

Wilder was able to break almost all the rules here—similar to the unthinkable transgressions Preston Sturges got away with the year before in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. The two leads—Fred McMurray and Barbara Stanwyck—are fiendishly duplicitous from the second they set eyes on each other, Stanwyck’s husband is a growling, boozing bear, her step daughter is pinch-faced and shrill, the step daughter’s boyfriend just a gigolo. Even the bit players—like the toad of a woman who bitches about having to reach up to the top shelf for baby food—are consistently unpleasant. The only character to display any integrity and meaningful intelligence is Edward G. Robinson as the scowling, grousing claims manager Keyes. An unabashed proto nerd, Keyes is clearly Chandler’s favorite character and in many ways like Chandler himself—far more so than Chandler’s idealized alter ego Marlowe.

It’s no accident McMurray and Stanwyck just aren’t that pleasant to look at, he, with his prominent brow ridge and vaguely simian muzzle, looming over the not just petite but tiny Stanwyck, she, with that intentionally silly blonde wig and a look on her face like somebody’s holding a heavily soiled diaper under her nose, exuding all the sexual charisma of live bait. It would be pretentious to call the effect Brechtian, but the upshot is the same—to keep us from identifying with the leads and instead see them clearly for who they are—two endlessly devious schemers ultimately just too dumb to rise above their fates.

That’s not to say there aren’t false notes—Richard Gaines as the pompous insurance company president feels like he wandered in from an early talkie, and Porter Hall just can’t seem to shake his screwball comedy roots, doing a couple of takes that would have been perfect in Sullivan’s Travels but feel like they dropped from the moon here.

It’s impossible to say enough good things about John Seitz’s cinematography. Not only does he perfectly express the gist and the nuances of Wilder/Chandler’s screenplay but he summons up an entire genre whole within a single film, creating all the iconography—rooms sliced by the light through Venetian blinds, shadows that are less shadows than doppelgängers, the constant imminence and threat of night, and so on—without ever once lapsing into mannerism, channeling German Expressionism while making it natural, inevitable instead of showy like it would be in a Hitchcock—or Tim Burton—film. There’s a shot two minutes in, as Neff’s car pulls up in front of the Pacific Building, with streetlights piercing fog and a web of interurban cables crisscrossing the frame, that’s so redolent of Stieglitz that you want to cry. But it’s not lingered on, instead kept up just long enough to establish a mood before the film breathlessly moves on. But that shot subtly sets the tone for everything to come and continues to resonate clear through to the final fadeout, and beyond.

Whatever transfer Amazon is leaning on isn’t great but good enough, apparently derived from a somewhat damaged print so that there’s some tonal fluctuation to the image throughout but nothing too distracting, and clean enough that you can appreciate Seitz’s cinematography—the same tepid recommendation I had to give the presentation of his work in Morgan’s Creek. Would I like to see a 4K restoration? Sure. Something that matches the resolution of the original would of course be a step up and judiciously tempering the flaws in the print is nothing anyone could argue with. But I’m not interested if it ends up looking sanitized, digitized, “improved.” If the result ultimately doesn’t feel like it came from 1944, why bother?

Anointing “greatest films” has always been something of a squeaky wheel phenomenon—driven more by hype and box office and fads than quality—a situation that’s only gotten worse as more and more holdouts succumb, like pod people, to Rotten Tomatoes’ statistically driven groupthink. Individual discernment and taste are on the verge of being pummeled into submission and dumped by the wayside, victims of the human weakness for cheap guarantees and the marketing-driven zeal for consensus. Double Indemnity isn’t mega-budget, isn’t littered with stars, doesn’t have any big action scenes, can only claim one poorly executed matte shot for a special effect, and thankfully didn’t spawn any sequels, let alone franchises. It exists about as far from the land of the blockbuster as it’s possible to be. It’s just a solid piece of filmmaking, as strong an effort as Hollywood has ever made or likely ever will make, a work that’s unlikely to ever date because it rests above social trends, changing fashions, and political agendas. It’s an escape without being escapist, artful without being arty, brutally honest without being preachy—something to be savored, not gulped or munched. By any meaningful standard, it’s one of the great American films. Maybe the greatest.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Whatever transfer Amazon is leaning on isn’t great but good enough, apparently derived from a somewhat damaged print so that there’s some tonal fluctuation to the image throughout but nothing too distracting, and clean enough that you can appreciate John Seitz’s genre-defining cinematography

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO ENLARGE

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC