review | Serpico

It might be the archetypal ’70s movie—and looks surprisingly good on Amazon Prime—but does Serpico still hold up as a film?

by Michael Gaughn

August 5, 2022

This review was originally going to be along the lines of, Serpico isn’t that great but it’s such a perfect embodiment of the ‘70s film that it’s worth writing up just to provide a guidepost for anyone trying to wrap their arms around that genre. But about two-thirds of the way in I realized that, while the movie definitely has problems, it rises above them magnificently for a while, and in a way that makes it worth anyone’s time to wade through all the rest of it.

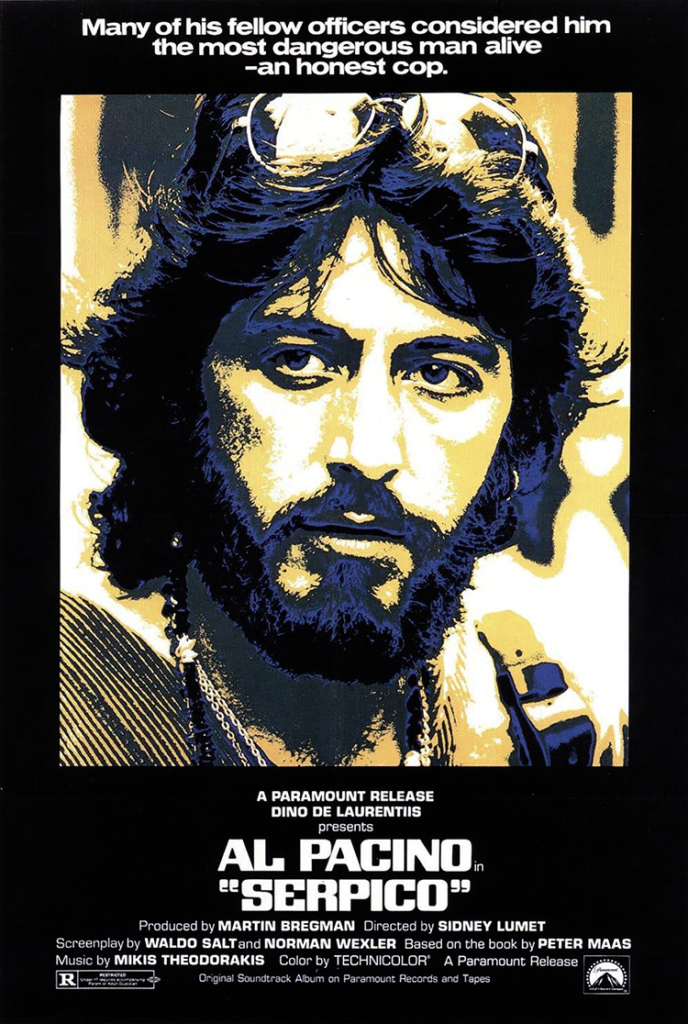

I’ve always had my doubts about Serpico, and the years haven’t treated it particularly well. Directed by Sidney Lumet, starring Al Pacino, cut by Dede Allen, shot entirely in New York during the city’s period of worst decay in a gritty documentary-inflected style, it is the epitome of the ’70s film and, as such, helps highlight the virtues and underline the flaws of that genre.

By 1968, American filmmaking was in complete disarray, and throughout the early and mid ‘70s, everyone was just kind of guessing, throwing everything they could think of at the screen. Since nobody was quite sure what to shoot or how it would come together, movies from the era tend to suffer from over-zealous editing, and there are gratuitous bursts of that here. The ‘70s were also the absolute nadir of the film score. With lush orchestral arrangements decidedly out of favor, strait-laced composers struggled, post The Graduate, with how to work pop, rock, jazz, and funk into their cues. Since little or none of that came naturally, the results were often unlistenable—a case Serpico only bolsters. And nobody knew what to do with women. Here, they magically appear for Pacino to bed down and then just kind of hang around for exposition, the obligatory nude scene, and to have something to break up with.

The general uncertainty over who was actually coming to the movies and why resulted in a fact-based film saddled with way too much TV-movie sentimentality, especially during the first half. Trying to cling to traditional notions of good guys and bad guys while also trying to be fashionably anti-authority, it aims for hard-boiled and knowing but often comes across as woefully naive. But even the rawer Taxi Driver isn’t immune from all that, feeling like the product of a hyperactive adolescent who’s trying to reprocess the reality of New York at a more rudimentary level that he can handle. (Scorsese was far from alone, of course, in reacting to the ‘60s and ‘70s by resorting to emotional regression. We wouldn’t have the blockbuster cinema of the ‘80s, which has become the superhero cinema of the 2000s, without it.)

It’s not like Lumet wasn’t capable of better ‘70s films—he aced the genre two years later with Dog Day Afternoon and, in 1981, did a better Serpico with Prince of the City (although it’s been a while since I’ve seen the last named, so it might not hold up as well as memory suggests). Here, you sense him trying to figure out how much to retain from ‘50s and ’60s crime dramas, how much the movie should adhere to the urtext The French Connection while also pulling back from the wall-to-wall brutality, and how much he should strike out on his own. Serpico finally clicks when it gets to the police investigations, and once again, it’s process that comes to the rescue, lending a movie some solid bones when there’s nothing more substantial to be found.

It’s Pacino, though, and not Lumet, who ultimately provides the glue. He does an engrossing job of convincingly and wrenchingly portraying Serpico’s massive struggles with his conscience as he’s left all but alone in an impossible situation. At those moments, Lumet knows enough to just step back and let the acting be the film.

And Amazon Prime’s 1080p presentation (via Roku’s ScreenPix) really brings to the foreground what a—as odd as this word might sound in this context—beautiful film this is. It’s not pretty—true to its documentary influences, every frame is spattered with the requisite grime. And it’s plagued by that fog-filter look that marred almost every movie of the era through Jaws and beyond. But, for great stretches, it’s shockingly good, evocatively expressing the material, which is, of course, the goal. It’s hard not to gape at some of the sequences, this transfer is so true to the original. It’s so good, I fear for what might happen if Serpico gets dipped in the 4K HDR vat—especially if Paramount is doing the dipping.

The music is surprisingly well recorded and effectively mixed in stereo—but, again, really has no place in this film. It reminded me of the mix for Breakfast at Tiffany’s, where the dialogue was crisp and clean but not very imaginatively placed, while the score existed in a kind of Van Allen Belt outside the movie proper.

Sidney Lumet wasn’t a master filmmaker but a frequently inspired one, so most of his movies are at least worth a watch and some have displayed prodigious staying power. Serpico starts out vaguely in the former camp but begins to become intriguing and then compelling once it crosses the midway point. Pacino did consistently engaging and often riveting work in the early part of his career, sometimes achieving the impossible, and he summons up a standout performance here. So you can approach this as a decent enough effort by some supremely talented people trying their best in a world they don’t fully understand, or you can see that confusion and uncertainty as the very lifeblood of that most important decade in filmmaking—not just for what it created but for the seismic reaction it spawned—and see Serpico as its most apt manifestation. Either way, it makes for a provocative night at the movies.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | While every frame is spattered with grime and plagued by that fog-filter look you expect to see in a ’70s film, this presentation is, for great stretches, shockingly good. It’s hard not to gape at some of the sequences, the transfer is so true to the original.

SOUND | The completely unnecessary score is surprisingly well recorded and effectively mixed in stereo, while the dialogue is crisp and clean but not very imaginatively placed

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO ENLARGE

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC