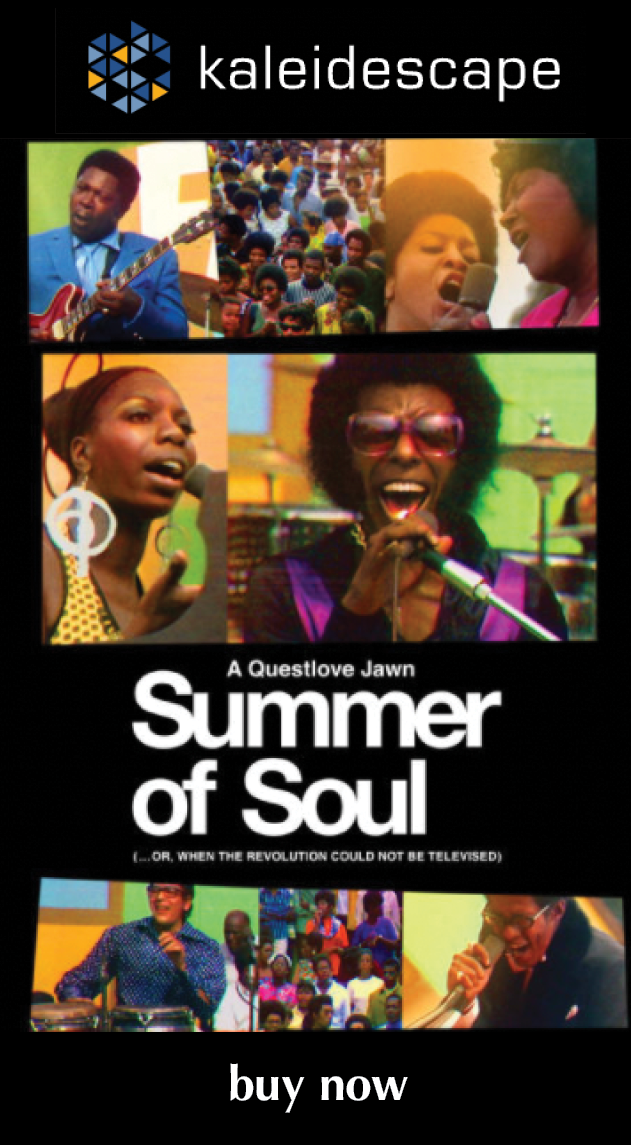

review | Summer of Soul

This documentary of a 1969 Harlem music festival is less about the performances and more about the culture & politics of the time

by Dennis Burger

February 11, 2022

To describe Summer of Soul ( . . . or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) as the best documentary I’ve seen in recent years would be a disservice to it and to you. It is, without question, one of the best films I’ve seen in ages, regardless of genre. It’s a masterclass in film editing, although it’s never ostentatious in its cutting. Its pacing is hypnotic, resembling the timing and tempo of an album more so than a film (and not for the reasons you might suspect given its subject matter). It manages to be shockingly comprehensive and broad without losing focus. It is, not to put too fine a point on it, going straight onto my exceedingly short list of truly perfect films.

If you’ve seen the trailer, you know already that it’s a film about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, held at Mt. Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park). It has been described as the Black Woodstock, and although clips from the festival have surfaced from time to time—perhaps most notably in What Happened, Miss Simone?, one of the few legitimately good documentaries on Netflix not starring David Attenborough—no one could muster the will or the financial backing to do an entire film about it until Roots drummer and frontman Questlove took it on.

While all of the above is a perfectly satisfactory summation of the heart of the film, it’s so much more than that. Summer of Soul is the most intersectional film I’ve seen in I don’t know how long. I hesitate to use that adjective and would have instead substituted literally any other descriptor that might have worked. But none does. Make no mistake about it, though: Despite being defiantly and unapologetically political, the film isn’t tainted by modern political biases.

What do I mean by “intersectional”? In short, the main thing Questlove seems to be saying is, “You can’t understand X if you don’t understand Y,” and the variables he plugs into that equation range from the political and societal to the spiritual and secular, from fashion to art to civil rights to the heroin epidemic that ravaged Harlem at the time. As a Tolkien nerd, perhaps my favorite intersection Questlove plants a street sign into—before driving right on by, confidently and casually—is that you can’t understand shifts in culture without understanding shifts in language. And vice versa.

It’s interesting that the film doesn’t dwell on this—or any point, for that matter. And I can’t know for sure if there simply wasn’t time to linger or if Questlove simply respects the intelligence of the audience too much to belabor anything (an all-too-rare treat these days), but it hardly matters. The thing is, while you’d think the breadth of topics would be too much for one film to chew on, Summer of Soul manages to be cohesive and focused largely due to its use of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival as its center of gravity. Literally everything ties back to it.

In his audio commentary—available on Kaleidescape—Questlove discusses a much longer first cut that ran close to three and a half hours, and how it differed from the final edit. It seems clear that most of what got excised—aside from additional performances by Sly and the Family Stone and so many other acts on the verge of exploding into the public consciousness shortly thereafter—involved side journeys that got too far away from the festival itself in an attempt to provide an even larger, though less concise, historical context.

Part of me wants to see that extended cut and part of me doesn’t because as both a historical document and a work of art, the 118-minute cut is not only a complete statement but also an incredibly tight and rhythmically fascinating jam, and it’s borderline impossible to imagine it being improved upon by additional material.

Bottom line: I’m kicking myself for not watching Summer of Soul sooner. It was made as a Hulu exclusive and originally released last summer. And although I do subscribe to that service for reasons I don’t quite understand, I’ve never been able to bring myself to watch a proper film on it, as its video quality is unacceptable in most cases. As it turns out, this isn’t a film where image quality makes much difference. The festival was shot on video and not well preserved, so it’s riddled with aliasing, moiré, clipping, chromatic aberrations, and mosquito noise, and no attempt has been made to clean it up à la Get Back.

Because of that, Kaleidescape’s UHD presentation is practically indistinguishable from Hulu’s for large swaths of its runtime. Only the modern interview segments with attendees and performers reveal any meaningful differences in image quality, largely due to the fact that some lost high frequencies in the Hulu presentation result in a slight dulling of textures and some minor loss of the finest details, all of which Kaleidescape allows to shine.

Kaleidescape also presents the film with a Dolby TrueHD Atmos soundtrack, which is a little baffling given that the 5.1 mix on Hulu was overkill to begin with. The audio is sourced from mics on the stage, of which there weren’t many, and although fidelity and tonal balance are surprisingly good, there just isn’t much going on in either the surrounds or—in the case of the Atmos track—the overhead channels. Thankfully, the Atmos mix does no harm to the experience, which was my biggest fear. It’s largely unnecessary, but at least it’s never gimmicky.

But none of the above really matters in the moment. The material is so engaging that you quickly forget about the rawness of the footage or the limitations of the audio recordings. But it does raise a question: Why buy it on Kaleidescape instead of watching it for free on Hulu?

It comes down to the aforementioned commentary track. This is a commentary for people who hate commentaries. It is, in effect, an alternate version of Summer of Soul, packed with historical perspective beyond the scope of what could be shown in the film, and crammed full of anecdotes that run the gamut from hilarious to elucidating. It feels like a two-hour hangout session with the smartest person you know, just without the laborious pedantry.

One of my favorite bits involves Questlove describing his creative process, specifically all the little things he did to make Summer of Soul his own without inserting himself or his biases into the work. For one thing, he chose to start the film with a Stevie Wonder drum solo. For another, while he discusses his struggles with resisting the urge to cheat in the editing process, he does reveal some of his few sleights of hand, including the fact that he occasionally re-synced the sound with the footage because he couldn’t bear to see some of his black brothers and sisters clapping on the 1 and 3 instead of the 2 and 4—although he did leave in many instances of such because to remove them entirely would have been dishonest.

In short, this is a version of the film you absolutely need to experience, and the Kaleidescape download is one of the few ways of doing so, outside of buying the Blu-ray. What’s more, the only extras included on the disc that aren’t available on Kaleidescape have long since been released to YouTube.

Even if I can’t convince you to check out the commentary, you owe it to yourself to watch the film at your earliest convenience. Again, I’ve barely nicked the paint on this incredible experience, which centers on a wonderful but forgotten music festival but also touches on everything from the moon landing to the repercussions of the assassinations of MLK and JFK to the power of music and the purpose and nature of art. The fact that it does all of this elegantly and with a cohesive narrative thread is itself something of a minor miracle.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

PICTURE | The recent interview segments look fine but the music festival was shot on video in 1969, so it’s riddled with aliasing, moiré, clipping, chromatic aberrations, and mosquito noise.

SOUND | The audio for the Atmos mix was sourced from mics on the festival stage, and although fidelity & tonal balance are surprisingly good, there isn’t much going on in either the surrounds or the overhead channels.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC