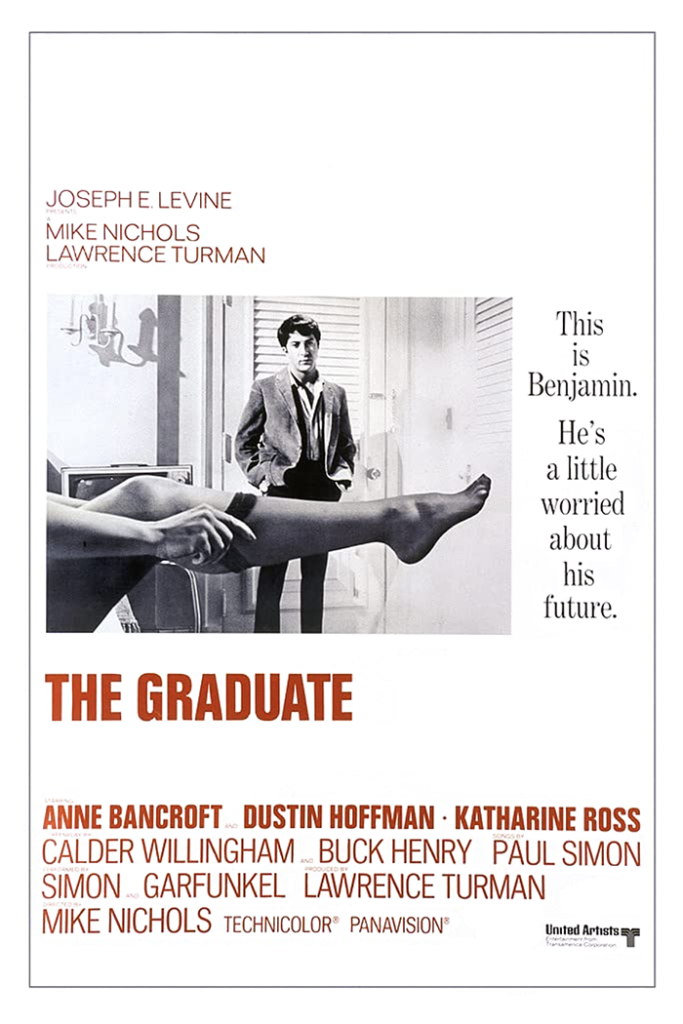

review | The Graduate

Is it possible to strip away all the nostalgia and see Mike Nichols’ generation-defining film for what it is?

by Michael Gaughn

April 27, 2023

It’s pure luck that I stumbled upon Mike Nichols’ The Graduate on Prime after having reviewed his Carnal Knowledge last week. One is a masterpiece, one of the greatest films of its era; the other is a hopeless jumble, triaged in post—and all the stitches still show. And what applies to which is probably the exact opposite of what you’d expect, given the consensus of the mass-mind.

What follows is going to be a little more abstract and analytical than usual. But when you’re dealing with a movie whose reputation stems mainly from people’s identification with a character and an era, you have to cut through all the sentimental attachments to have any hope of judging the film itself. Much like Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Graduate has been embraced by successive generations out of nostalgia and because it can be so easily reinterpreted to fit the preoccupations and prejudices of the present. But being a convenient and malleable receptacle for blind emotion is usually antithetical to what ought to define a good movie.

The Graduate is known as being one of the more radical mainstream films of the late ’60s, one of the first to portray the extreme alienation of youth within the Establishment, to show what was once called the Generation Gap as anything other than a punchline, to assimilate disruptive techniques from foreign films, and to use rock-inflected songs in a non-jukebox way. One of the main reasons it’s still embraced is that, like almost every film made today, it’s filled with superficial gestures of rebellion—or at least acting out—but is at heart conformist. Which points to the bigger reason for its continued popularity—

In college, during the Post-Structuralist era, interested in seeing if mainstream movies actually can be radical, I did a Proppian analysis of The Graduate. (For those unfamiliar with Vladimir Propp, his Morphology of the Folktale is an incisive, elegant, and beautifully written analysis of the structure of fables.) I expected The Graduate, given its reputation, to present a challenge, and was surprised—shocked, actually—to find that not only didn’t its bones lead it in any new directions but that it’s a textbook example of a classic fairy tale—not only in the obvious way of Ben as knight, Elaine as princess, and Mrs. Robinson as wicked queen, with Benjamin going off on an archetypal quest/rescue, but down to the micro level of how these tales traditionally play out.

In other words, we continue to watch The Graduate mainly because it provides the emotional satisfaction of Snow White and Sleeping Beauty—both the originary tales and their Disneyfied reinterpretations. Nobody at the time of its release realized that all this lay at its core, and I’ve seen little evidence that many have realized it since. But once you connect the dots, it all makes sense.

And, given what a disjointed patchwork the film is, it turns out that underlying structure is the only thing holding it together in any meaningful way. There are at least four distinctly different shooting styles—not as any deliberate strategy but from an inability to figure out how to convey the material. It doesn’t know when it’s hitting the comedy too hard (Mrs. Robinson’s famous pursuit of Benjamin feels painfully long now, and Hoffman’s reactions to her advances feel forced and sitcomy), and it transitions into drama with a heavy lurch—which once seemed innovative but, in retrospect, could have been handled much more deftly.

I could continue to cite examples, but you get the idea. The only other thing I’ll point to is the ending, which is poorly motivated, ineptly executed, and ultimately the kind of kitchen-sink pile-on you’d expect to see at the end of a Beach Blanket movie. The only reason we buy into it is because the knight is rescuing the princess from her captors. And the only reason we buy into that is because the entire film has been (probably without being aware of it) preparing us for that moment. And the point I ultimately want to make from all that is that, with very few exceptions, radical art—whether we’re talking pop culture or more serious art—feeds from deeply conservative roots that determine it far more completely than most people would be willing to admit.

The other point worth making, because it’s the other reason for the film’s longevity, is that the worst thing you can do is forge any kind of emotional identification with the characters in a movie. At that point, you’re no longer experiencing the film on its own terms but selfishly using it to bolster your own ego (even if you’re not aware that’s what you’re doing). So there’s no way your impressions of it can be even remotely objective—which has been the case with the vast majority of people who’ve seen The Graduate in the 56 years since its release.

If you decide to give The Graduate a gander, nothing about its presentation on Prime should dissuade you. I have to emphasize yet again how good movies can look on the service and how that’s happening more and more often, making the fingerprints of streaming harder and harder to detect.

The iconic image early on of Ben with his head resting against an aquarium is both solid and beautiful. The “Ben at the pool” montage, accompanied by “The Sounds of Silence” and “April Come She Will,” is similarly solid despite reflections, hot spots, and frequent sparkles. There is a decent number of soft frames but they can all be attributed to the film itself, as can all the mismatched and overexposed shots, the inconsistent tonal range, and some scenes exhibiting far more contrast than others. The earlier eras of home video helped smooth over many of these flaws, but streaming is reaching the point of consistently offering up transfers exactly as they are, warts and all.

“Warts and all” pretty much describes the soundtrack as well. It’s not terrible and a little bit of basic cleanup would make a huge difference, but it’s sad to hear so much distortion on the Simon & Garfunkel tracks. That said, the solution isn’t to splice in pristine, digitized mixes that feel alien to the era and violate the spirit of the film.

That people find it acceptable—and are encouraged—to impose their subjective biases on movies might be the biggest argument against granting most films any real stature. If the audience is responsible for creating at least half the experience of a “great” film, what exactly is making it great? Once fads die down and the audience moves on and no longer feels the need to pump a movie up, it’s as if it never existed—which is when marketing steps in to push the nostalgia angle hard to try to inflate it all over again. All this is undeniably part of the life cycle of any film, and something studios and filmmakers have gotten increasingly adept at cultivating and exploiting. It seems all but inevitable we’ll soon reach the point where it will become impossible to judge any film on its own merits because, very much intentionally, there’s no there there.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | Nothing about The Graduate‘s presentation on Prime should dissuade you from giving it a gander. The reproduction is solid throughout with any warts solely attributable to the original film.

SOUND | The sound’s not terrible and a little bit of basic cleanup would make a huge difference, but it’s sad to hear so much distortion on the Simon & Garfunkel tracks

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC