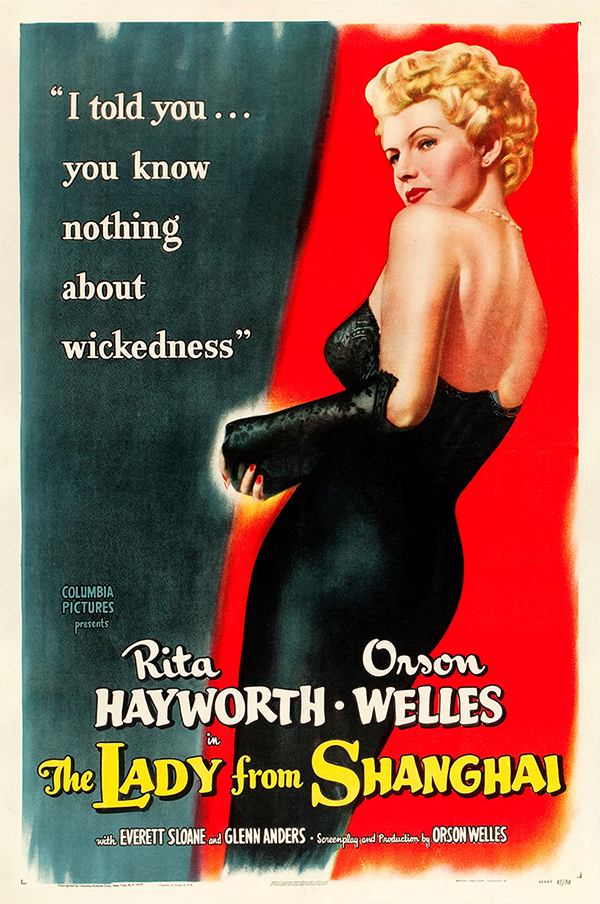

review | The Lady from Shanghai

Probably Orson Welles’ most eccentric—and biting—film, Shanghai features two for-the-ages supporting performances

by Michael Gaughn

June 1, 2022

Why review an older film like The Lady from Shanghai if it’s not a restoration or appearing in 4K for the first time? Partly because certain older films are far more vibrant and relevant than others and it’s worth it to pluck the gems from the pile. Partly to underline for anyone who’s gotten burned by checking out catalog titles online that the consistency of the quality of their presentation has improved tremendously of late. And partly because, in a culture obsessed with living in a perpetual present and with erasing history on its way to erasing memory, it’s important to push back by emphasizing the value of the past.

Citizen Kane kind of sells itself. It hasn’t yet been pulled down from its pedestal—and hopefully never will be—so you don’t really need to say a lot about the film itself when reviewing something like the 4K release. But what about the other Welles, the stuff he tried to make within the studio system but that was inevitably extensively retooled on its way to release, the films you have to work at a little to appreciate because you have to peer around all the obstructions erected by the studio if you want to catch glimpses of the film Welles originally made?

The Lady from Shanghai wasn’t just reshot and recut by Columbia, it was savagely beaten into submission. But enough of Welles’ effort survives in the theatrical release, even though broken and bruised, to make watching it a satisfying experience. In fact, the tension between what he created and what the studio did to it actually played into his hands, making the film even edgier, even more collage- and dreamlike.

Shanghai comes from the period when Welles had exhausted almost all his credit in Hollywood and was on the verge of becoming a caricature, ensconced so deep inside his arrogance that he was all but blind to when he just looked silly. That too much of his smugness shows through to make him believable as a wide-eyed innocent in no way diminishes the value of this film. He offers up so much else to be savored that it’s more than worth it to look beyond his perpetual gloat.

Shanghai is usually labelled a film noir, and I guess that pertains, as far as it goes—but it doesn’t go far enough to define what it really is, which is a dense cluster of character studies of a depth and incisiveness—and of the kind of people—Hollywood hardly ever allows. And the irony of that is that this movie isn’t really that much about the romantic leads, Welles and Rita Hayworth, but about the two law partners, Grisbee and Bannister. You can watch it for the stylistic stuff, but you’ll be missing the real meat if you don’t surrender utterly to what Everett Sloane and Glenn Anders put forth.

Sloane delivers one of the best performances ever captured on film—the kind of thing he might have been able to do in Kane if he wasn’t relegated to playing a thinly-drawn ethnic stereotype and if he and Joseph Cotten weren’t in constant danger of Welles eating them alive. You’re led to believe early on that his character is the villain, and he is, in a way, but who’s the villain, and the definition of villainy, is so slippery in this film that you’re left more with the impression of a brilliant but broken man whose physical paralysis has come to cripple his entire being.

As for Glenn Anders—there’s something miraculous about what he pulled off here. His performance is famously eccentric, but gloriously so, and fully, and impishly, fledged. It shouldn’t work, but it does, partly because Anders and Welles make his madness insidious. While Sloane’s crafty attorney is to some degree descended from Victorian mustache twirling, Anders is something new, the craziness of a heedless society embodied, that craziness then spreading out and permeating the rest of the film. (It’s hard not to watch Anders now and not see anticipations of Jack Nicholson’s Jack Torrance in The Shining.)

Partly because of all the reshoots, and partly because of the state of the film, the look of Shanghai is all over the place, but the moments that are solid—especially the camera lingering over Hayworth on the Circe, the probing closeups of Sloane, and the jarring closeups of a sweating, twitching Anders—look strikingly good in 1080p on Prime. Unless somebody does a digital makeover and turn this into a kind of 4K comic book à la The Godfather—which isn’t likely—Shanghai will always look this uneven. But if you see this movie as off-kilter to its core, as you should, then that’s OK.

(A quick update on the whole “films looking good on Prime” thing: I’ve been spotchecking titles, pretty much at random, and you can’t take this as gospel, but I would say the odds are about 3:1 of a film looking pretty damn good if you dive into the catalog offerings. There’s a lot of room for improvement, of course, but Prime is becoming a boon for anyone who cares about the entire breadth and depth of film and not just the fleeting shiny objects of the moment.)

As usual, there’s not much to be said about the sound. It probably wasn’t that good to begin with, and this presentation is probably faithful to whatever there was to work with. Wish they’d balanced out the disparity between the dialogue and the music cues, and between some of the scenes, but that’s not a dealbreaker.

Every time I want to dismiss Orson Welles as more than a bit of an overweening jerk—which he was—I find myself getting pulled deep into something like Lady from Shanghai or Touch of Evil, works so sublime and subversive and of their own world they almost forgive all his many sins. Almost.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC