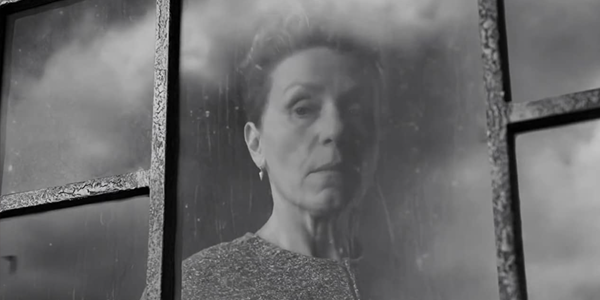

review | Writing with Fire

Shot mostly with cellphones and inexpensive cameras, this documentary is an engrossing examination of journalism and new technology in lower-class Indian society

by Dennis Burger

March 25, 2022

Writing with Fire, the Oscar-nomianted feature-length debut by filmmakers Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas, is as prime an example as I’ve seen lately of a documentary that serves as both window and mirror. On the surface, it follows the journalists of Khabar Lahariya, a newspaper run by Dalit women—the lowest of the lowest-class citizens of India—as they transition from operating as a small weekly paper to creating a digital enterprise that functions primarily in the new-media space.

Brewing just beneath the surface, though, is a sweeping indictment of corporate news; a discussion about finding the balance between journalism as a responsibility and media as an industry; a rumination on the critical distinction between neutrality and objectivity; and perhaps most importantly, a meditation on all the topics dissected by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their seminal 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media.

How much of that is intentional I can’t know, of course. Probably very little. It seems as if Ghosh and Thomas set out to tell the story of these women in the midst of a transformational moment and deeper truths simply rose to the top. But it hardly matters. Intentional or not, they’ve created a film that contains not only resonant universal truths but also insights into a culture most Westerners can’t begin to pretend to fully comprehend.

To give just one example: Early on, as the paper’s chief reporter, Meera Devi, discusses with her staff the importance—and dangers—of having a larger social-media presence, one of the young writers reveals that she has never even touched a smartphone. Her family only owns one between them but she has never used it out of fear of damaging it. And now she’s being told that this is an essential tool of her job.

There’s another scene toward the middle, which will no doubt keep me awake tonight, that I wish I could put in front of everyone I know and beg them to absorb it and reflect on it. One of the three main journalists at the heart of the documentary is attending a press conference, sitting across the desk from a high-ranking police official. As she refuses to accept canned answers from him and continues to press him for the truth, a mainstream correspondent sitting behind her berates her for her dogged approach. Later, outside, he lectures her about the importance of playing nice with authority figures, of maintaining access, of offering praise before criticism.

The film doesn’t bother spoon-feeding this to the viewer, opting instead for a show-don’t-tell approach, but this small scene serves as an especially impactful commentary on how the people for whom our institutions function at all, no matter how inefficiently, are always the first to silence those who are completely failed by those same institutions when they dare speak out.

There are numerous other examples but they ultimately all boil down to one point: This is a study in contrasts and commonalities, of the universal juxtaposed against the deeply personal, of the unique dangers these women face placed on equal footing with the shared truths we should and would be discussing out in the open if only more of us cared.

I wish Writing with Fire were more readily available but, best I can tell, right now it’s only available in the U.S. to rent or buy on Amazon Prime Video. A physical media release is slated for late April 2022, but only on DVD.

That old SD format is probably more than sufficient, although Prime delivers the film in HD with Dolby Digital+ 5.1 audio. There isn’t much to say about the picture, given that it was shot on, as best I can tell, a mix of cellphones and consumer-grade mirrorless cameras with a run-and-gun approach. As such, the quality of Amazon’s streaming presentation varies from shot to shot, although when conditions are right, lighting is sufficient, and the resolution is there, the picture quality is about as good as HD gets. More often than not, the source material is a bottleneck in terms of quality, though. It is what it is.

The audio, on the other hand, was a tough nut for me to crack. For about the first hour, I was distracted by some seriously weird idiosyncrasies in the mix. Ambient and environmental sounds were well placed in the surround soundfield, but voices tended to hover a few feet in front of me in the form of an amorphous and indistinct blob of ethereal audio. They even followed me as I moved from one side of my sofa to the other. Granted, I don’t understand Hindi, so intelligibility wasn’t the problem. But it was still unnerving.

I eventually figured out that the issue was that I had my system’s Dolby Atmos up-mixing capabilities turned on, which isn’t usually a problem with films of this sort since there isn’t much to up-mix. But for whatever reason, voices are placed in both the front left and right channels here—not the center—and, worse, they’re slightly out of phase. Because of that, Dolby Surround doesn’t recognize the split vocal tracks as a common signal that should be combined and routed to the center and instead spreads them out into the surrounds and overhead speakers. When I changed my system to the Pure Direct setting—which bypasses all DSP and turns the preamp into a straight decoder, not a processor—voices took their rightful place toward the front of the room but still nowhere near the middle of the screen.

If any of the above seems critical or needlessly technical, that’s not my intention. It’s simply that I encourage you to watch and appreciate this film, and if you’re doing your watching in a home cinema environment, I want you to have the best experience possible.

That’s not to say that Writing with Fire is perfect, even ignoring the technical shortcomings. At 96 minutes, it positively whizzes by, and there are several story threads I wish we could have sat with for another 15 or 20 minutes here and there. But I’d far rather spend time with a film that leaves me wanting more than one that overstays its welcome, even when the subject matter is as important as this.

Dennis Burger is an avid Star Wars scholar, Tolkien fanatic, and Corvette enthusiast who somehow also manages to find time for technological passions including high-end audio, home automation, and video gaming. He lives in the armpit of Alabama with his wife Bethany and their four-legged child Bruno, a 75-pound American Staffordshire Terrier who thinks he’s a Pomeranian.

PICTURE | Because of the quality of the source material, Amazon’s streaming presentation varies from shot to shot, but when conditions are right, lighting is sufficient, and the resolution is there, the quality is about as good as HD gets

SOUND | Ambient and environmental sounds are well placed in the surround soundfield of the 5.1 mix, but voices can be indistinct and badly positioned if any kind of upmixing is employed

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC