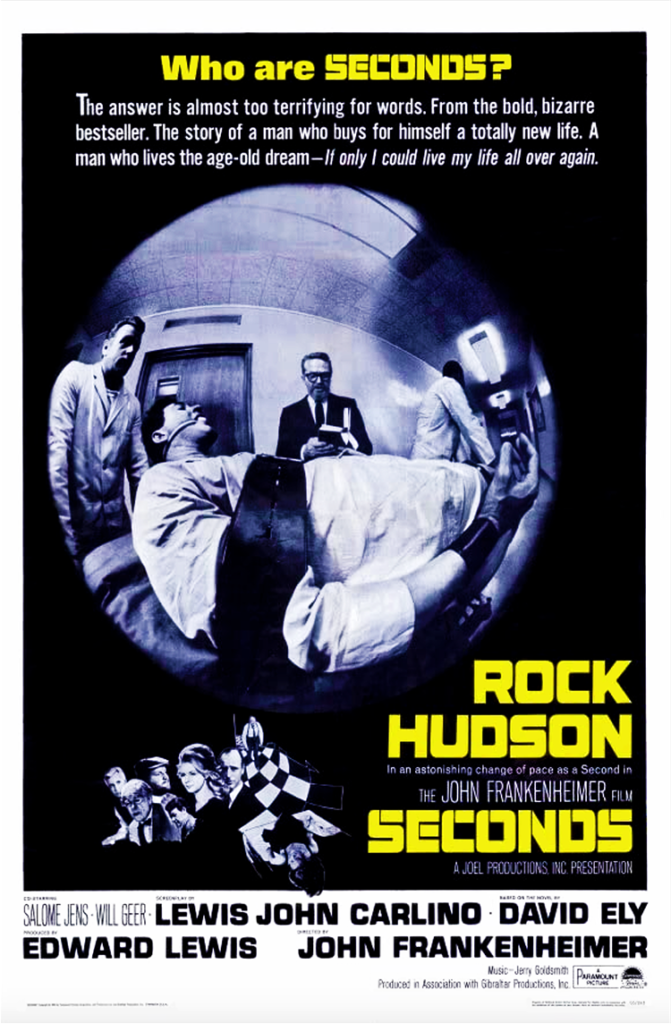

review | Seconds

A arch portrait in alienation, this 1966 John Frankenheimer shocker might be more important for who it influenced than for what it is

by Michael Gaughn

November 20, 2022

It’s not really a horror movie but it’s got some pretty good jolts along the way. Not really science fiction, it would be meaningless without its sci-fi trappings. A portrait of suburban disenchantment and angst à la Updike and Heller, it doesn’t go far enough down that road to fully qualify. “Psychological thriller” probably comes closest but calling it that shortchanges everything else. John Frankenheimer’s Seconds is undeniably something but it’s virtually impossible to put your finger on exactly what. Probably the most appropriate description would be “mid-‘60s Gothic,” but what does that mean?

What’s indisputable—although Frankenheimer might not have been aware of it and likely never saw the film—is that it’s the spiritual twin of Carnival of Souls, one of those detached portraits of utter alienation that started popping up beginning in the mid 1950s. Souls’ Mary Henry and Seconds’ Arthur Hamilton/Tony Wilson indisputably share the face of the same troubled coin—and that also makes it a descendant of the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the film that first raised the cry that there was something deeply rotten at the heart of Mid Century culture.

It’s also indisputable—although again likely a more unconscious than conscious influence—that Seconds springs directly from Hawthorne, not just because of its rarified/stylized world and use of typification that borders on allegory but also because it adopts the kind of sci-fi framework Hawthorne developed in stories like “The Birth-mark,” “The Artist of the Beautiful,” “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” and, most pertinent here, “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment.”

And that kinship also points toward the fundamental problem with Seconds—while it does feel very much like a Hawthorne short story, it needed to be at least a novella to work. The neat pattern of introducing a character into an artificial microcosm, giving them a too easily achieved path to bliss only to have them realize to their horror that they’ve actually been led down to Hell, and then wrapping it up with a twist, is just too linear and one-note to sustain a feature film.

The film—I really can’t attribute this directly to Frankenheimer because there’s no way to know if he was aware of it—compensates for all that by becoming an exercise in style, one that leans heavily on European art movies, introducing Antonioni-like longueurs to at least put up the front of a serious film, and to pad out its run time. And in all that—and many other ways—it’s a progenitor of Lynch. It’s impossible to watch the Saul Bass credit sequence (one of his best—which is saying a lot) and not think of Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, or Blue Velvet. And everything from the stylized compositions, lighting, and camera moves to the callow ambiguity, meaningless pauses and elisions, and overall archness of the exercise, feels very much like Lost Highway, Mulholland Dr, or Fire Walk With Me.

It also feels very much like Rosemary’s Baby, with the scene where the Reborns subdue Rock Hudson’s Wilson when he gets out of line very much like the seniors subduing Mia Farrow for her Satan rape. And it’s also very much like Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner, with the central figure robbed of his identity by a bureaucratic/technocratic corporate society that promises paradise but only delivers the carrot of endless tantalizing diversion while perpetually poised to bring down the stick.

And that goes to the heart of why I’m bothering to write up a film that’s got so many flaws—because it represents a point of intersection for far too many important things in the culture to ignore. No, it doesn’t get many of the fundamentals right but it’s such a tantalizing slice of the zeitgeist, channeling so many powerful currents, anticipating what was about to boil over and what wouldn’t come to the surface for at least another 20 years, that it’s impossible to look away. On a more base level, it is creepy as all get-out, and it’s well worth taking the ride at least once. Just don’t expect it to do much for you the second time around.

Frankenheimer tried his damnedest to be a first-rank director but his stuff just won’t stick. The Manchurian Candidate is the closest he got to making a great film but it wears too much of its anxiety on its sleeve and is too unnuanced, too dead-certain in its paranoia to have the requisite resonance and heft. Everything that feeds Seconds is valid and needs to be expressed but Frankenheimer just wasn’t deft or deep enough to translate it.

The biggest problem is that he doesn’t really care two craps about his main character or his dilemma and seems to treat him with a kind of contempt. The result is that it feels like Frankenheimer is just as cold-blooded as the entrepreneurs and minions who engineer Hamilton’s rebirth and demise, so it’s all kind of like watching a jaded medical-school professor do a lecture-hall dissection of a cadaver.

But it’s not like master cinematographer James Wong Howe (Sweet Smell of Success) wasn’t eager to try to deliver on anything Frankenheimer might have asked from him. Howe, through the framing and camera moves and documentary-ish, high-contrast, sometimes blownout look, all of which was about four decades ahead of its time, sets a tone and a mood that would have been mesmerizing for the duration if Frankenheimer had had a better grasp of his material.

The same goes for composer Jerry Goldsmith, who delivers a truly accomplished and innovative score (up there with the one he turned around on a dime for Chinatown) that at times references ‘20s and ‘30s horror while somehow avoiding slipping into kitsch, and evokes fin de siècle Viennese chamber music without slipping into pretension, lending the film a lot of depth it would have otherwise lacked.

And I’m actually going to say some nice things about Rock Hudson, whose career, very much like Marilyn’s, stemmed from being game to be whatever the public wanted to project onto him without pushing back by trying to express anything authentically intrinsic to him. In other words, he was fine with—or at least reconciled to—being nothing but a big, empty hunk. The result was that he never looked entirely comfortable on camera and never felt entirely right in any of his roles. He had to have been aware of all that because he seems to channel it here to portray someone who not only just doesn’t belong but, like Mary Henry, just doesn’t exist.

The HD transfer available through Amazon Prime is good—remarkably good. While the print isn’t pristine—there are some damaged frames and occasional circles for reel changes—there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with it. It’s crisp, tonally consistent, and faithful enough to the original film.

Noble failure? Flat-out failure? For some reason, going there just doesn’t fit. Seconds is undeniably an experience, an experiment that clearly didn’t succeed but also didn’t utterly fail. Crucial to blazing a fruitful and prodigious trail, it isn’t just some bizarro curiosity. The problem—and I wish there was some way I could be a little more precise about this—is that there just doesn’t seem to be enough there there.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC