Review: The Pink Panther (1963)

also on Cineluxe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

to stay up to date on Cineluxe

The only Panther film worth watching, with Clouseau as a fully realized character instead of a one-joke cartoon

by Michael Gaughn

April 24, 2023

There is only one Pink Panther movie. Blake Edwards managed to create an almost perfect modern-day farce with the original, 1963 film. All the various sequels were just cynical attempts to exploit a brilliantly conceived comic character, reducing Clouseau to an increasingly repugnant cartoon and trotting out Peter Sellers like he was some kind of circus freak. The greatest sin of all is none of the sequels are even remotely funny. The only upside is that the massive revenue they generated allowed Edwards to make films like Victor/Victoria and 10.

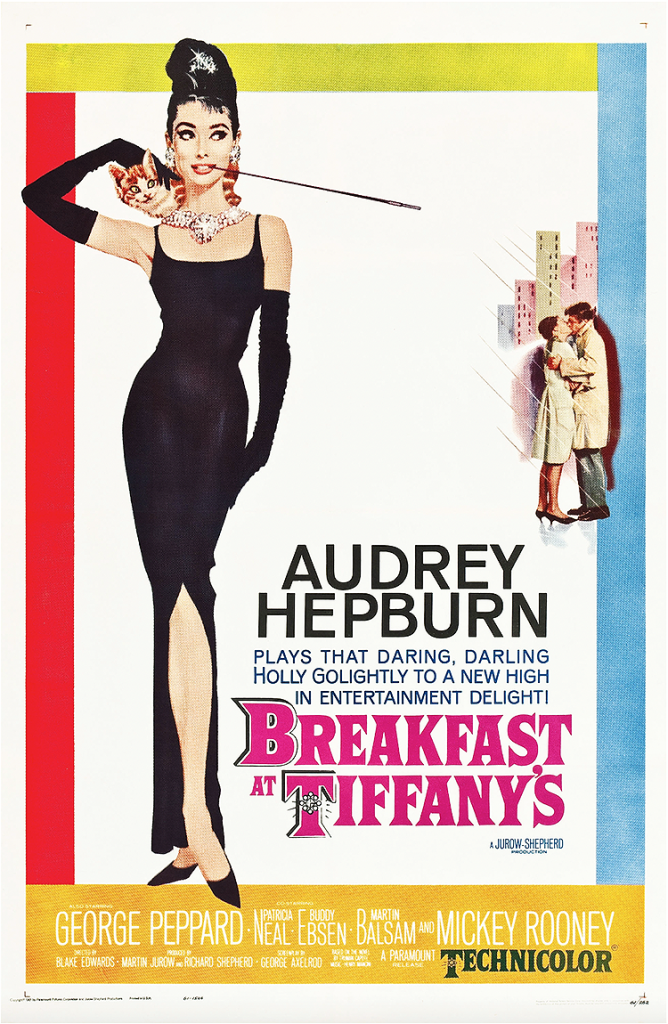

Edwards had a weakness for sight gags, an itch he was able to scratch with varying degrees of success throughout his career. He used them to liven up early, fluffy efforts like Operation Petticoat and The Perfect Furlough but failed to show the necessary restraint in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, where they often feel like they were spliced in from another movie. The relentlessness of the gags chokes The Great Race, inducing fatigue by the end of the first reel when there’s still more than two hours of movie to go. On the other hand, he turned that relentlessness to his advantage with The Party, a successful modern attempt, with a nod to Tati, at a silent film.

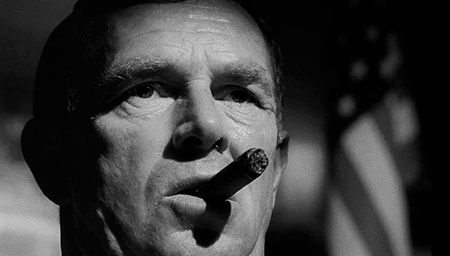

The only time he achieved an ideal balance between story and gags was The Pink Panther, which works because he was able to use the conventions of classic stage farce without making the film look stagey—and because he came up with Clouseau. And because Peter Sellers played the character when he was at the absolute height of his powers. Sellers did The Pink Panther and Dr. Strangelove pretty much back to back—two of the supreme examples of comic acting on film and, considered together, an unsurpassed feat.

Peter Ustinov was originally supposed to play Clouseau, which would have guaranteed that the film would be nothing more than a pleasant temporary diversion fated to sink beneath the waves of time. The rest of the ensemble is solid enough but in no way exceptional, which allows Sellers to exist within it as an independent force of nature, but without the obligation to have him in every scene—one of the reasons the original film wears so well and the sequels seem so ponderous and one-note now.

But for everything Edwards does well here, even he can’t sustain his well-modulated conception for the duration, and the whole thing starts to sag badly after the transition from Cortina d’Ampezzo to Rome, where the need to stage a “wild” party and a jewel heist simultaneously, followed by a “wild” chase scene—all of them forced exercises that feel more obligatory than inspired—threatens to sink the whole enterprise. (Richard Lester’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, made two years later, suffers from the same flaw, only worse.) The ending almost works and almost reestablishes some kind of equilibrium, but you’re basically left with a warm memory of what transpired during the earlier parts of the film, once you repress the egregious missteps.

The transfer on Prime bears all the earmarks of being the same Blu-ray-quality transfer available on Kaleidescape—which means it’s pleasant enough to watch with no significant distractions, but a movie of this popularity and stature deserves better. The famous opening titles look dirty and even a little murky, and some wear and tear with the elements is apparent throughout the film. That said, the colors are for the most part vivid, and streaming is able to handle things like the blinding white slopes of Cortina without a hiccup—something that would have been unthinkable a couple of years ago.

The audio could use some work. The mix from the time probably wasn’t great but I find it hard to believe it sounded this bad. This is probably Henry Mancini’s best score, which, aside from a few too-obvious “joke” cues is mainly wall-to-wall mood music—which is more than fine because it’s exactly what the material called for and a merciful break from the pretentious Post Romantic drivel that drips off most movies like syrup. But it’s painful to hear Mancini’s tasteful arrangements sounding like AM radio. On the other hand, it would be a disaster to give them a latter-day goosing—the Living Stereo treatment that make his cues on the most recent release of Breakfast at Tiffany’s sound like they existed in a parallel universe from the dialogue tracks.

It’s a shame Blake Edwards got lazy. Clouseau, married but as a perpetual cuckold, as lost running the gauntlet of domestic life as he is the one of crime and the police, and unburdened by the comic relief of a manservant, the Little Tramp removed from the Victorian era and saddled with the pathetic delusions and neuroses of the present, would have been a much richer character than the merely convenient and monotonous figure of the sequels. But at least we have the original Panther film to appreciate on its own terms and as a glimpse of what could have been.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

PICTURE | The transfer on Prime bears all the earmarks of being the same Blu-ray-quality transfer available on Kaleidescape—which means it’s pleasant enough to watch, with no significant distractions, but with enough evidence of worn elements to cry out for a restoration

SOUND | The audio could use some beefing up so Henry Mancini’s tasteful arrangements don’t end up sounding like AM radio

© 2023 Cineluxe LLC