The Strange Journey of Tom Waits

A casual encounter with an early Waits album leads to a radical reevaluation of the arc of his career

by Michael Gaughn

August 29, 2020

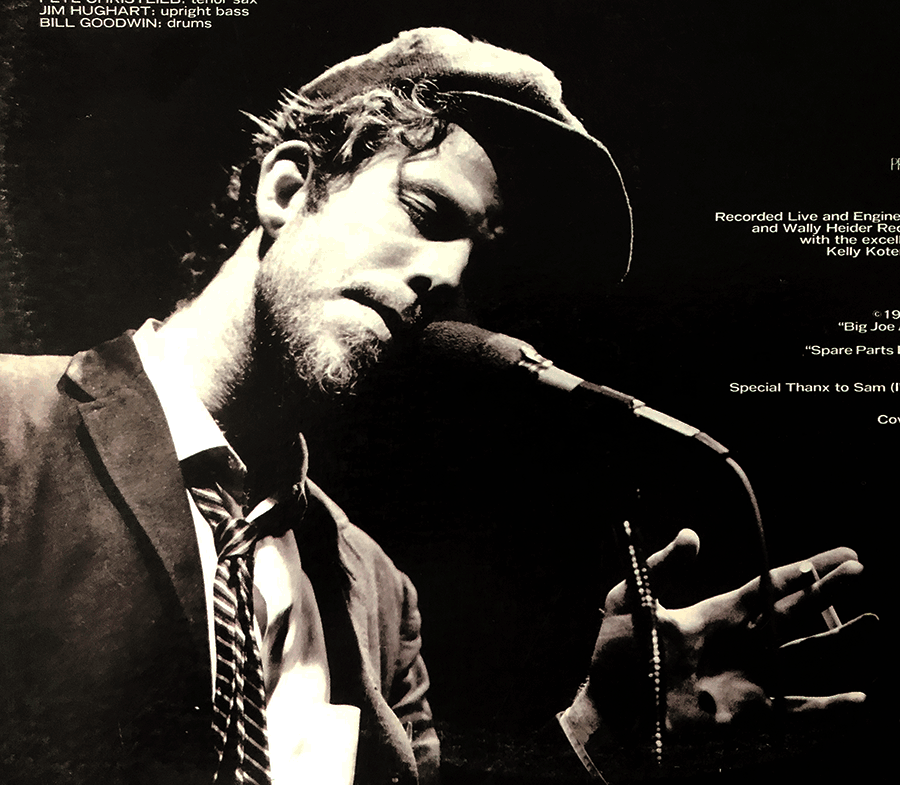

Last Sunday evening, I had a chance to do something I hardly ever get to do—devote all my attention to listening to some music. After uncorking a Portuguese red I’d never tried before and flicking on a single, small incandescent lamp, I unsheathed and cued up Side One of Tom Waits’ Nighthawks at the Diner.

The whole exercise felt a bit like a ritual, and I guess you could consider it the musical equivalent of comfort viewing—going to one of the very few things that has always made me feel grounded to reaffirm its ability to ring true no matter how much the world has changed around it.

A 1975 Bones Howe-produced two-LP set recorded in front of a live audience at LA’s Record Plant, Nighthawks is Waits in full hipster mode, from the period when he was using his faux Kerouac routine to disarm audiences while going up hard against the pop-music mainstream. You were far more likely to know him at the time for Rusty Warren-type retreads like “The Piano Has Been Drinking” and “Pasties and a G String” as the epic “Tom Traubert’s Blues.”

The first cut, “Emotional Weather Report,” is an extended monologue-quasi-song with Waits resorting to every corny Vegas-comic gag to ingratiate himself, winking so hard the whole time that you can’t help but grin. “I’ve been playing nightclubs and staying out all night long, coming home late—gone for three months, come back and everything in the refrigerator turns into a science project.” “I’m so goddamned horny the crack of dawn better be careful around me.”

But parts of the song that had just struck me as laugh lines before—“with tornado watches issued Sunday for the areas including the western region of my mental health, and the northern portion of my ability to deal rationally with my disconcerted emotional situation—it’s cold out there”—felt strangely bittersweet, veering toward wrenching, this time around.

Then, as Nighthawks slipped into “On a Foggy Night,” I had a kind of epiphany. It’s common knowledge Waits went through one of the most radical transformations in pop-music history, but it didn’t hit me until then that it was far more a maturation than any kind of rebranding. Once you go beneath the jokey surfaces, there’s actually an amazingly consistent through-line to his work. Songs like Nighthawks’ “Better Off Without a Wife” and 2002’s “All the World is Green” might seem to exist in completely different worlds, but just shift the emphasis a little here and there and the actual distance between them is so slight it’s barely there at all.

A lot of the stuff on Waits’ initial albums might seem gaggy and trite, but view it through the lens of everything he’s done since Swordfishtrombones and you realize how fundamentally poignant those early efforts are. They don’t have the rigor, incisive, often bitter, irony, or unflinching moral probity of his later work, but they aren’t just the throwaway ditties of some one-trick booze-addled clown.

Then, around the time of “Warm Beer and Cold Women,” I was graced with another seeming insight—that not just his later efforts but the whole of Waits’ work stands at the pinnacle of the American songwriting tradition. Realizing how much Nighthawks honors and feeds from everything that preceded it, in a way then-popular stadium rock never could, made me realize how early on he blew past his contemporaries.

Most pop performers write songs, but they’re not songwriters. Never having fully immersed themselves in either the history or the craft, instead donning and shedding styles the way they’d try on designer Ts, they not only don’t have a good grasp of the basic mechanics but lack the reverence and awe that would inspire them to match or exceed the best efforts to date. But it’s clear in retrospect that Waits is, and always was, a master, able to pluck the most vital, fertile, and redolent elements out of the musical stream until he was eventually creating songs where every turn of phrase was a perfect evocation of a different aspect of the American tradition, pivoting seamlessly from, say, Hoagy Carmichael to the Delta blues to Kurt Weill to Big Mama Thornton to Stephen Foster to early Satchmo to Tin Pan Alley to a Salvation Army band without ever using any of it as a crutch, and making it all feel whole.

I’m not saying Waits stands alone above his peers and their successors. Randy Newman occupies similar ground. Both used novelty songs early on to win over audiences, lacing them with just enough irony to let the intelligentsia know they were fashionably cynical, but both have gone far deeper than their contemporaries, showing a decidedly unfashionable vulnerability and sentimentality that actually lifts their work to a whole other level.

Newman, of course, is pared down, almost diffident compared to Waits’ flamboyance and radical experimentation. But each is a fully formed songsmith and not the usual mercenary faddist. And, far too honest in their work, neither would stand a chance if they were starting their careers during these far more intolerant and censorious times.

None of the above is meant to suggest that I drifted from listening to Nighthawks into some kind of brooding meditation. Whatever thoughts I had came unbidden, and flickered just long enough to jot them down here. Maybe they were just a product of my mood or a reaction to listening to early Waits against the backdrop of the strangely trivial and parlous present. Or maybe it was just the wine.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC