Theo Kalomirakis:

A Personal History of Home Theater, Pt. 2

Theo discusses the ’90s—the decade when he learned his craft, created his signature work, and gave birth to an entire industry

by Michael Gaughn

January 21, 2022

The 1990s saw Theo Kalomirakis create and hone not just the style but all the various techniques that would forever define home theater design. And it all happened within his first few commissions—which is especially impressive when you realize that he leapt into the field with no formal training as an interior designer.

It was the decade not just of his earliest work—which quickly established his reputation and caused him to be sought out by millionaires, billionaires, movie stars, sports figures, and business and political leaders—but of his first international commissions and his first coffeetable book, Private Theaters, which features, among other work, the Ziegfeld, Uptown, and Gold Coast theaters discussed below.

While much of Part 1 of our interview focused on the emerging technology that allowed Theo to indulge his passion for collecting and watching movies, the emphasis here is more on the blooming of his aesthetic, and on the succession of eager, generous clients who gave him the opportunity to introduce his exuberant showman’s flair into their homes.

—M.G.

When did you get your first commission to do a theater?

1989.

So, by the end of the ‘80s, people were starting to show a lot of interest but since you didn’t really have any training as a designer, you had to sort of learn on the job.

Exactly. I just was pushed to do it but I didn’t find my stride until the ‘90s. The first home theater was in the Hamptons. It was called The Sweet Potato. I did that one with help from industry people that used to do commercial theaters, because there was no such thing as custom integration then. At the end of the year, I left my art direction job at American Heritage and incorporated. The first day of Theater Design Associates was January 1, 1990.

So home theater really began at the beginning of 1990.

Before then, there was no such thing. I called the company Theater Design Associates because I wanted it to sound like there were a lot of people.

Besides the Sweet Potato, this other guy, Skip Bronson, who turned out to be a very good friend, said, “I want to have a theater in my house in West Hartford, Connecticut.” He drove down and saw my Roxy and became enamored with it. He said, “I want a lobby, I want a box office—I want everything.” So I did The Ritz for Skip, and immediately I got the Barry Knispel job—immediately—about 1992.

That’s the Ziegfeld, right?

Yes. That was an amazing learning experience because I was given an unlimited budget to do things no one does today—expensive millwork, expensive hand painting. I was able to work with a lunatic in furniture design, Frank Pollaro, whose work can be seen now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He does the most spectacular reproductions of antique Art Deco furniture. You cannot tell from the original. He was doing just millwork for the rest of the house and somehow we connected. I wanted to do something different, Barry wanted to do something different, Frank wanted to do something different.

You’ve said before that the best clients are the ones who have a sense of adventure or creativity or play, because they’re willing to experiment.

Absolutely. You feed off that. You can’t fall in love with someone that doesn’t love you back. It’s as simple as that. I was lucky enough in the beginning to bump into people that were my duplicates in thinking—who had the same kind of enthusiasm.

But also there was still an inherent thrill at that point in the idea of having a theater at home, so the clients were riding that wave as well.

We were explorers. We charted new territories.

Barry wanted an Art Deco theater for the Ziegfeld, so I got every Deco book I could get my hands on. And I realized I didn’t need to reinvent the wheel because there are actual visual references for everything that signifies that era. So I singled out elements from Art Deco landmarks and built a library of design elements that I synthesized in the theater. This is the theater that made me start saying that you don’t invent—you steal, but you steal creatively.

Was the Ziegfeld when you felt like you’d arrived at something?

Yes. That was absolutely the pinnacle of what I was trying to do. And it was a very abrupt rise to the top, to where you have control of your medium and you are given the opportunity to just do what’s in your mind.

With the next theater, which was The Uptown for Larry and Nora Kay in Toluca Lake, he wanted to do a lot of Deco elements from The Pantages [theater in Los Angeles]. They were available, because I had found the sources, but if I had cast them the way they are they would have been out of scale. So, in my pursuit to create details that were as good as the originals but in a scale that would fit in a theater, I found my way to what used to be called staff shops, which are the movie-studio workshops where they make set ornaments out of clay. I started going to the shop at Warner Brothers and then at 20th Century Fox, where I discovered molds. And I asked them to reproduce them in different scale because all these facilities have sculptors, and they were doing things that would fit the scale of a particular movie set.

The next theater was The Gold Coast, which I did for another incredible patron—Lloyd Wright, the nephew of Frank Lloyd Wright. It was just client after client after client that pushed me to reach out to do things that hadn’t been done before. That was the blessing of my career.

When was Dean Koontz?

That was towards the end of the nineties, but it started right away. Dean was one of my first clients but the project was huge.

Was that the biggest theater you had done to date?

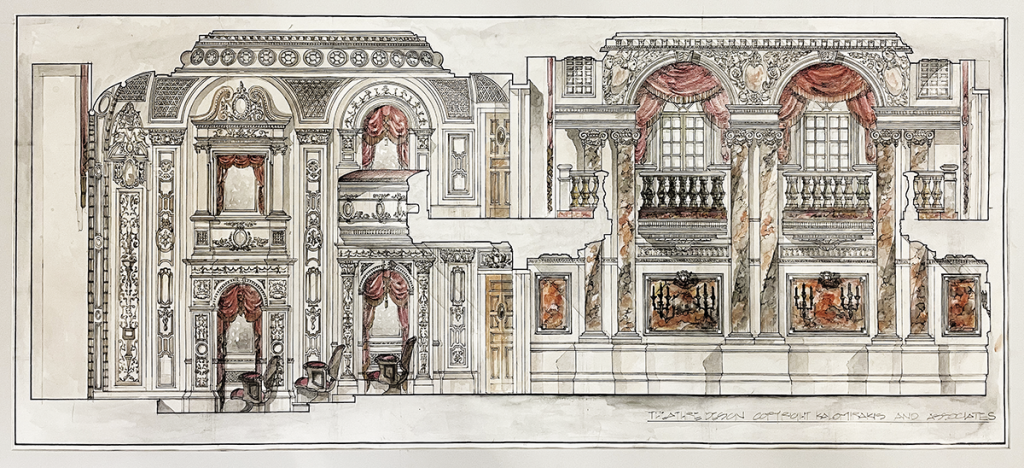

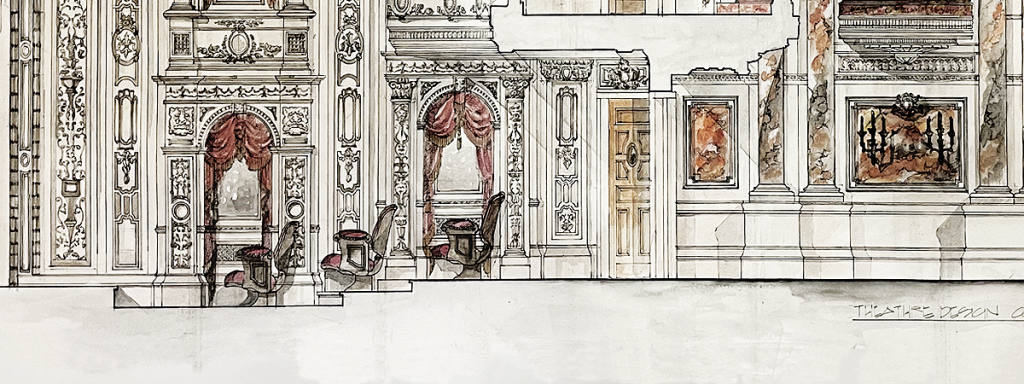

Absolutely. And he was very intent on having me do a recreation of the Opera of Paris, and I loved it. He financed a trip to France, and I came back with 2,000 pictures and did drawings. There were not computers back then to do digital drawings, so it took forever. But then in the course of the first two years we shed the classical thing and

click on the image to enlarge

switched to Art Deco because his house developed slowly into a Deco house. And that’s when we veered towards Frank Lloyd Wright because he loved Wright.

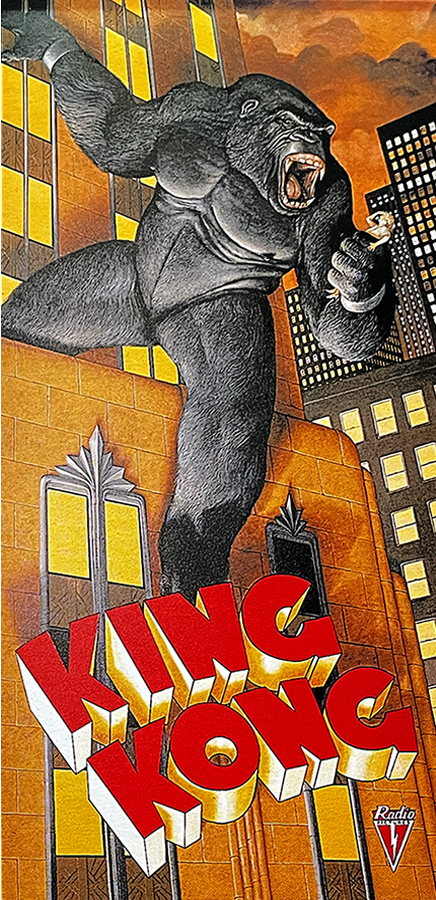

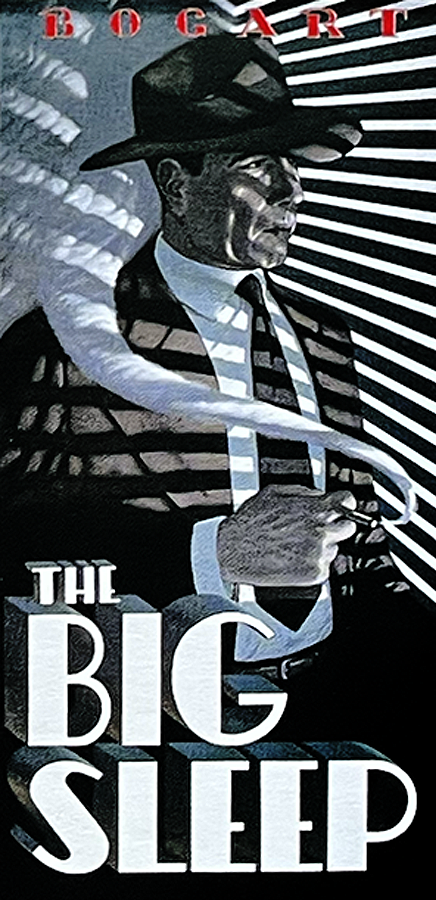

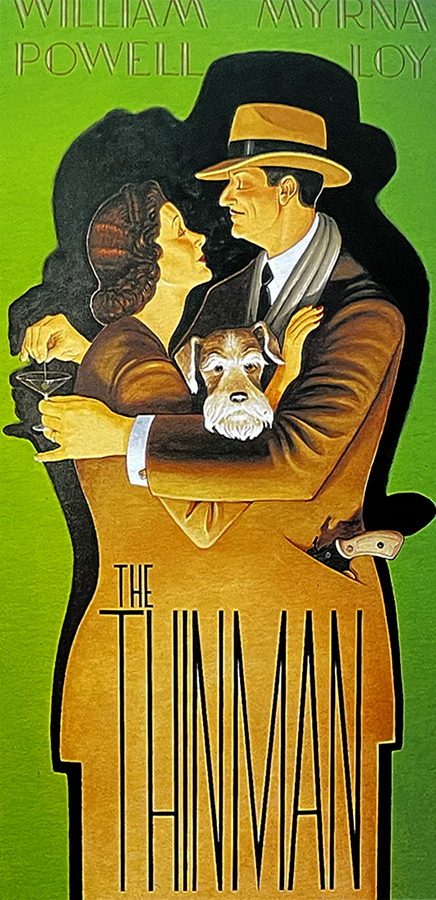

Again, another client with unlimited money to put in millwork and detail and original art. He was so obsessed with this thing that he didn’t even want original posters in the theater, so he had an artist create wonderful interpretations. You would think instinctively, “What the hell are you doing recreating a poster for The Maltese Falcon or The African Queen?” First of all, we couldn’t have found all of them in three-sheet configuration, big posters. They’re perfect recreations of the era of the poster, not the original poster. They were another indication of a confluence of people who just adored movies.

How many seats were in the Koontz theater?

There were four rows—at least 16—about 20, 24. And there were balconies all around for additional seats but it was mostly for effect.

Is Seth MacFarlane’s theater bigger?

Of course. His has 40 seats.

Is that the biggest one you’ve done?

Ah, definitely.

The key differentiator between you and other designers seems to be that you create from your passion for watching and escaping into movies, which you share with your clients, while a lot of the other designers are just creating a room to watch movies in.

It could absolutely be the differentiator. I was working in conjunction with the clients, while a lot of other designers are separated from the client so while they create a room for watching movies, it’s a room the clients don’t really want. They do it because everybody has a theater. The disconnect is double—not only do many designers not do a real theater because they don’t have a passion to design it, the clients don’t have a passion for the room. The funny thing is that the demand for home theaters has exploded through the roof, but it’s lost its soul.

As you mentioned earlier, there needs to be that intense emotional bond between designer and client in order to spur something exceptional.

I would have never done anything if the clients hadn’t encouraged me. I would tell them stories about what it would be, and I had their rapt attention. “Yeah! Let’s do that.” I was like a pied piper, leading them on to something that was magical that they didn’t know how to express. They had it in them. They knew what they wanted. But I was able to articulate it for them via architecture.

They were all the same people—all the clients. They were all like children, in that they wanted to build movie palaces, they wanted to build paradise in their home. They wanted the ultimate escape, which is what I enjoy every night when I go to my own theater. When I’m there, I become Skip Bronson, Lloyd Wright, Dean Koontz, Larry Kay, Barry Knispel.

Coming Soon: Part 3—From 2000 to the Present

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

Theo’s hand drawing of his original conception for Dean Koontz’ home theater, inspired by the Opera of Paris. (Scroll down to see the complete original rendering.)

related features

an ebony cocktail-table top designed by Frank Pollaro

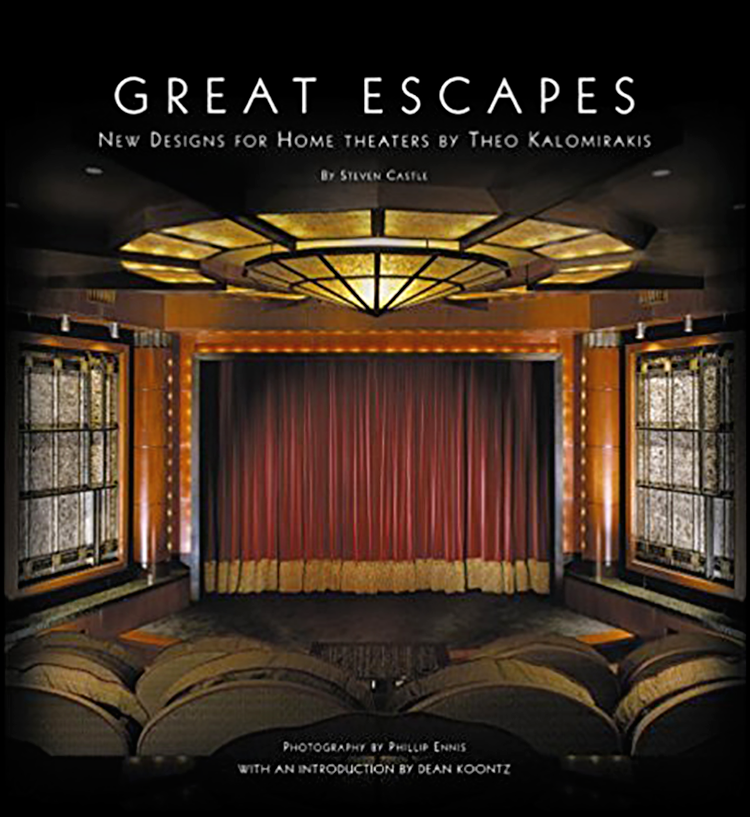

the original Opera of Paris concept for Dean Koontz’ theater evolved into this Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired Deco design

Theo’s second coffeetable book includes more about the Moonlight and the other theaters that set the standard for private cinema design

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC