What Have You Done With His Movie?

Brazil was hugely influential at the time of its release, changing movies forever, but nobody talks about it anymore. Why?

by Michael Gaughn

September 19, 2022

I approached revisiting Brazil with extreme trepidation. About a year ago, wanting to write something about my admiration for Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, I was horrified to find that it hasn’t held up at all, that it’s just an exercise in stylistic indulgence, as dull and thin and lifeless as tissue paper, and that the studio was right to be furious with Gilliam for pissing all its money away.

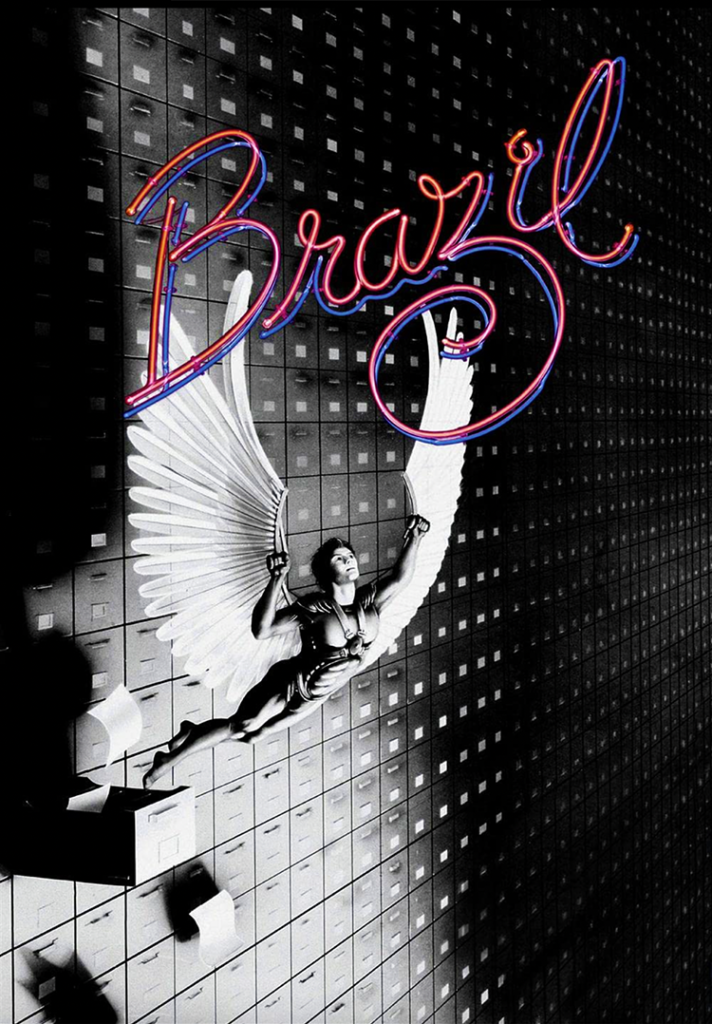

Certain things immediately set Brazil apart, though—all related to its reputation and influence and not the film itself but that still lend it some stature. It was the movie, thanks to Gilliam’s long and bloody battle with Universal, that established the modern conception of the director’s cut. And, thanks to the exhaustive and gorgeously presented Criterion boxed-set laserdisc edition, it set the standard for home video releases going forward, laying the groundwork for DVDs and Blu-rays, with their alternate cuts, extensive bonus features, and so on.

But all of that is obviously secondary to reapproaching Brazil as a movie. Adding to my concern was that, while all kinds of films from the mid ’80s are being buffed, repackaged, and remade because they appealed on a preconscious level to the uncritical child and teen audiences of the time, Brazil has faded from view. It didn’t make sense that something that had once had a seismic influence on moviemaking didn’t seem to be on anyone’s radar anymore.

Having now watched it again, I can affirm that it remains a masterpiece—a flawed one, more deeply so than most films of its rank, but still something that stands many tiers above almost anything else that was made during that mostly dismal decade. The irony is that it appears to be the things that make it great—specifically its very deliberate and trenchant reaction to the carefully calibrated vacuousness of popcorn cinema—that have led to its repression. But I’ll get to that.

Brazil is so labyrinthine and rich it’s hard to zero in on a best point of entry. It could be its style—so influential its presence can be felt in almost every movie made since, even if the filmmakers have no idea where that influence came from—but I think the best place to begin, oddly, is with Tom Stoppard’s screenplay. Gilliam and Charles McKeown get a screen credit for it too, but given that they’re the ones who made an unholy mess of Munchausen you have to assume Stoppard had something—or everything—to do with Brazil holding together as well as it does. (Sorry to be quoting Thoreau for the zillionth time, but there is something in his maxim that there’s no reason you can’t have your dream castle as long as you build a foundation beneath it as well.)

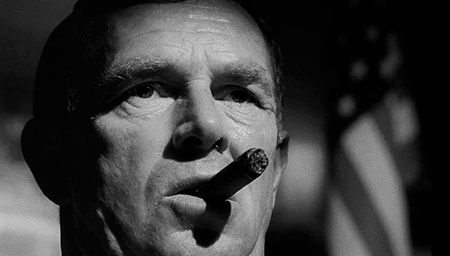

The casting is flawless—with one exception that comes dangerously close to sinking the whole enterprise. I didn’t fully appreciate until now how extraordinary Johnathan Pryce’s performance is, even when he’s doing material for Gilliam he doesn’t seem to be fully on board with. Pryce immediately establishes the contrast between the real and fantasy Sam through his presence alone, and he fully embodies both, even to the slightest details of their gestures.

Ian Holm’s Kurtzmann is similarly pitch perfect, as is Jim Broadbent as the obsequious plastic surgeon. (The precision of British acting can often feel affected but when it’s in a groove with the material, like here, it can be pure pleasure to experience.) De Niro is in full Rupert Pupkin mode, right down to the mustache, obviously enjoying not having to play De Niro for a change—and it’s sad that this was probably the last time he was able to get away with that.

Sheila Reid’s Mrs. Buttle is stunning—I never realized just how good until this time around. Everything pivots on the scene where Pryce brings her the refund check for her husband. If Gilliam hadn’t risen to the potential of the material here, if he had played it too light, the entire film would have foundered. But it remains powerful—with a lot of the credit going to Reid for bringing a tremendous depth and breadth of emotion to the character, the scene, and the movie, every ounce of which is needed to counter the more arch and glib material elsewhere.

(And any movie that includes a cameo by Raymond Chandler’s Orange Queen—“‘It’s the wall,’ she said. ‘It talks. The voices of the dead men who have passed through on the way to hell.’”—can’t be all bad.)

The one massive mistake is Kim Greist as the object of Lowry’s obsession. What was Gilliam thinking? She clearly isn’t comfortable with anything about the role, making her scenes just unpleasant to watch. The only explanation that makes sense is that she’s part of his savaging of the giggly adolescent conventions put in place by movie brats like Spielberg, Lucas, Zemeckis, and Ridley Scott, who clearly weren’t comfortable with women (and still aren’t) and instead leaned on tomboys for the traditional female roles. But you can get all that and still feel like Greist doesn’t belong in this film at all.

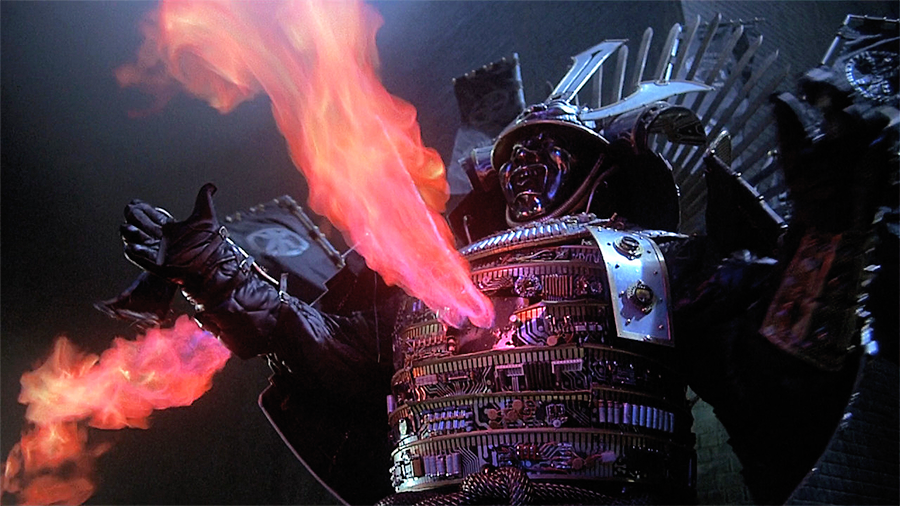

There’s so much to savor here, though, that you can even look past a bungled female lead. The intricacy of the staging is dazzling, with Gilliam exhibiting masterful control, never letting it become gratuitous or indulgent. And the fantasy sequences, surprisingly, still work—mainly because they’re actually about character and story and theme and not just an excuse to goose the audience awake every 15 minutes with some artificially generated excitement.

There are a few moments where Gilliam gets overly ambitious—which in itself isn’t a bad thing but does lead to some sloppiness in the execution. And he hits some rough spots at around the two-thirds point—like most movies do, usually because the director has come up with amazingly fertile and provocative base material but, not fully realizing its implications, begins to let it get away from him. Gilliam doesn’t completely lose control but his grip on the film, which was iron tight until that point, does start to weaken. And although the ending remains powerful, it becomes so inchoate that it veers damn close to becoming the kind of sound and fury cinema he was trying to skewer—partly because he severs the bond between plausible cause and effect too soon, seriously diluting the impact of Sam’s descent into madness.

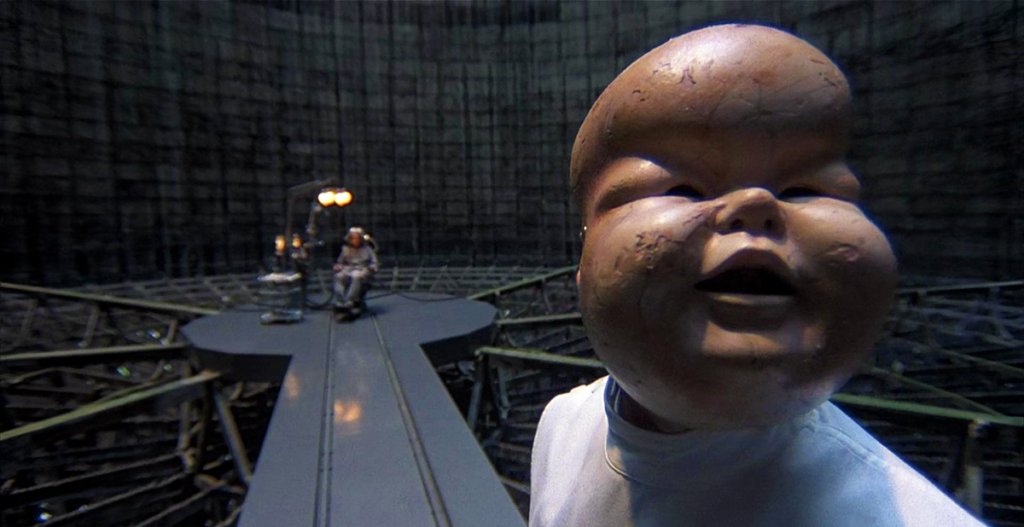

But let’s get to why Brazil has come to be shunned like a black-sheep uncle. Almost all dystopian films undercut themselves by fetishizing technology, which results in conveying the idea of, “Well, yeah, people suck, but aren’t their machines wonderful?” which in turn ends up feeding the whole capitalist/positivist impulse dystopian fiction is putatively meant to counter. In other words, by misplacing the emphasis, it ultimately gets us to take comfort in our own annihilation.

But Gilliam, very much like Godard in Alphaville, deliberately downplays the tech—here, making it decidedly analog and archaic—so Brazil doesn’t slip into the superficially dystopian but actually boosterish technocratic hoohah most sci-fi films embrace. Both he and Godard wanted to keep their movies about people, not their things—even if those things are meant to replace them.

Brazil has been swept under the rug because we now stand on the other side of our utter capitulation to both technology and bureaucracy. Having abdicated individual responsibility and placed our faith in a world of invisible hands, we would rather get lost in fantasy than be reminded that it doesn’t have to be this way, that there were and are alternatives. We’ve come to see not just controlling but defining bureaucracy as inevitable and rationalize its dominance through our indulgence in franchises, in all their various forms.

And we’ve completely bought into one of Gilliam’s sharpest barbs—that if you tell somebody convincingly enough that crap is caviar, they’ll accept it blindly and devour it with zeal. If we didn’t passively embrace that core tenet, our franchise-driven society would quickly shrivel up and die.

Most importantly, though, Brazil is about the death of romanticism and the limits and costs of fantasy, with how getting swept up in fantasy worlds is a far from free ride—something Woody Allen was examining, just as incisively, at that same moment in The Purple Rose of Cairo. Both Gilliam and Allen must have felt the same tremor because it was right after that the massive eruption of fantasy occurred that has since engulfed cinema, thriving on the beyond dangerous notion that this is all somehow healthy and benign.

Simply put, we’ve so completely become Gilliam’s creatures—and worse—that we don’t want to be reminded of how far we’ve fallen. Having come to believe it’s OK to exist suspended in a perpetual adolescence in a world of perpetual play, we want to purge anything that would suggest it could be any other way. Which is why watching Brazil is a better investment of your time than any movie released in the past 40 years.

Michael Gaughn—The Absolute Sound, The Perfect Vision, Wideband, Stereo Review, Sound & Vision, The Rayva Roundtable, marketing, product design, some theater designs, a couple TV shows, some commercials, and now this.

Brazil on Prime

That Brazil wasn’t one of the first titles out when 4K became available shows just how irrational the release patterns have been. That we’re now this far into the format without a release is an even stronger indictment. While Brazil deserves to be seen in 4K, I’m not so sure HDR is the best way to go. Being such a brash, stylistically extravagant film, it would take a very deft touch to bring anything meaningful to its look. Go too far and it would become all artificial highlights, whereas a constant murk is essential to its effect, or it could become cartoonish, in the pejorative sense.

In HD on Amazon Prime, it ranges from acceptable to surprisingly vivid—which is to say that it gives you an accurate sense of the brilliance of Roger Pratt’s groundbreaking cinematography but all feels just a tad flat. I suspect, without having any way of knowing, that a new transfer in 4K that hews as closely to the original material as possible without wandering into the netherworld of restoration would be a significant step up.

The stereo mix—apparently the original—is unexpectedly engaging, even exhilarating. I hadn’t realized how much Gilliam leaned on sound to compensate for his insufficient budget, drawing deeply on his animation background—how he used sound to significantly up the impact of the primitive cutouts in his Python vignettes—to make his visuals work.

Not a big fan of Michael Kamen, I’ve always liked his score here. It’s all basically just one big Mahler pastiche but it works because it underlines both the grandiosity of Sam’s fantasies and desires and the key theme of romanticism’s demise.

Thankfully, no one’s gotten around to enhancing the titles, which look, as they should, like type on film not a cold, distracting digital reinterpretation of the originals.

—M.G.

© 2025 Cineluxe LLC